Page 1 of 3

National Service

Posted: 15 Feb 2019, 04:06

by Stanley

I threatened to do it so here it is. My part in Russia's downfall....

In 1953 and 54 I was happily engaged working for Lionel Gleed on Harrod's Farm in Warwickshire and looking forward to going into Prees Heath college in 1954..... Read on....

After almost a year, in July 1954 a small cloud no bigger than a man’s hand appeared on the horizon in the form of a buff envelope. As everyone knows, these always mean trouble! It was my call-up papers for National Service. The Queen had decided she wanted my body for two years! I went to Birmingham, got graded C3, (not to be employed in infantry or artillery), and the army, with it’s usual stunning efficiency allocated me to the infantry, the First Battalion the Cheshire Regiment and ordered me to present myself for training at The Dale, Chester, the home of the 22nd. of Foot. There’s an old Jewish joke which I often quote, ‘If you want to make God laugh, tell him your plans’. My life was to change again completely, agricultural college went down the tube and I had absolutely no say in what happened. I was not consulted and another formative experience bore down on me. I gathered my possessions up and left Harrods for ever, it was bigger wrench than leaving home in the first place. In 12 months Lionel and Addie had transformed me from a callow little lad into a useful worker with the first faint glimmerings in his head of what life was actually about, being an able man, useful and a trustworthy worker. There was much more of course but that one sentence describes what should happen to every young person at that age. I was also as fit as a butcher’s dog, strong and healthy apart from my eyes and prime cannon fodder. Funny thing was I couldn’t think of any skills I had learned at school apart from the 3 ‘R’s that had been of any use at all. A bit of a puzzle…

NATIONAL SERVICE 1954

In July 1954 I left Harrods, went home briefly to dump my belongings and reported on the 15th of July to The Dale at Chester which was the main depot of the First Battalion the Cheshire Regiment, or as we were soon informed, the historic 22nd of Foot where I was to receive my initial training which would make me into a soldier. I became 23050525 Prvte. Graham S. What happened to me there will be hard for modern generations to believe. Even now, in 2009, it’s recognised that if the same methods were used today half the intake would go AWOL (Absent Without Leave). We were officially described as 21st Intake 54/14 and consisted of about 100 young men from all walks and conditions of life. The job of the depot staff was to convert us from raw recruits into trained, disciplined soldiers by September, in ten weeks. We had to understand Army methods, be able to do drill, handle a Lee Enfield .303 rifle or the Bren Light Machine Gun and be perfectly fit by the end of the training, the battalion would give us our specialised training on the job. The instructors had a very simple method of accomplishing their ends, they liquidised us and poured us into the army mould. This sounds like an exaggeration but is pretty close to the truth, their aim was to break you down and rebuild you in shape they wanted. Here’s how they did it.

The first job was to get us kitted out. We were taken down to the stores, given a kit bag and issued with everything we would need. As far as I remember it went something like this: Three pair socks, two pair ammunition boots, three vests, three underpants, three shirts, one set PT kit, two battledress, one pair denims, one beret, one tie, one pair gloves, one cap comforter, one tin hat, one set webbing, one set mess tins and knife and fork, one regimental cap badge, two yellow dusters, two boot brushes, one button-stick and a set of Cheshire shoulder flashes. Then we went to the tailor where our uniforms were marked for alteration. I remember that here we were measured by a lady of indeterminate age who paid a lot of attention to our inside leg measurement and used technical phrases like “giving us plenty of ballroom.” This was traumatic stuff for a young lad.

Laden down like camels we were then marched over to our billets where we slept about 30 to a room. A friendly corporal helped us sort out where to put all the stuff and then they fed us. We soon found out that everything on duty was done together, to a timetable and usually at the double. We never walked anywhere unless we were actually marching, it was an offence to be seen “slouching about”. After the meal they left us for the rest of the day to get sorted out. We were lucky, we had an old soldier who had re-enlisted with us and he showed us the ropes. Then to bed knowing we had to be up at 06:00 the following morning. This was a lie-in for me but some of the lads didn’t even know six o’clock in the morning existed!

The first night’s sleep in the barrack room was an experience in itself. I had always slept alone and having about 30 snuffling, farting and in some cases, weeping bed fellows took some handling. The following morning we were woken by the nice friendly corporal who had evidently undergone some sort of transformation during the night because he started our day by screaming at us and acting as though he was not only raving mad but very angry. We soon found out that this was par for the course, they were all angry madmen and we had to join them! Looking back I can see now that one of my biggest problems was that despite all the screaming and running about we didn’t actually seem to be accomplishing anything useful. My experience with Lionel’s man management techniques had taught me that we were most efficient when we worked quietly and efficiently towards a clear goal. I had to learn to file this useful knowledge away in the back of my head. The name of the game had changed and the sooner I bought into it the better it would be for me.

[It's the first time I have read this since I wrote it..... I don't know about you but I'm enjoying it. Brings back lots of memories!]

Re: National Service

Posted: 15 Feb 2019, 07:44

by Bodger

So far so good

Re: National Service

Posted: 15 Feb 2019, 08:04

by Stanley

Re: National Service

Posted: 15 Feb 2019, 11:49

by Tizer

Great stuff, keep it up please!

Re: National Service

Posted: 16 Feb 2019, 02:48

by Stanley

I can’t remember the actual timetable but I can recall everything that happened to us, not necessarily in the right order. The first thing was to cut our hair. I say cut, but it would be more accurate to say that we were taken away, penned up and sheared. Short back and sides and short on top was the standard cut. One or two officers had longer hair but everyone else was in the club. Then we were taken to the Medical Officer where we were told to strip off and line up to be examined, remember that in most cases, even our mothers hadn’t seen us naked for ten years! All the MO seemed to be interested in was our private parts, he used a pencil to actually move things about to examine them while we stood there, coughed when ordered to and thought of England. Actually my thoughts were on the pencil, I was wondering what they did with it afterwards, was it sterilised and used again or simply shoved back into a top pocket and perhaps chewed while in deep thought… Once the MO had made sure that we weren’t ruptured or disease ridden, we left what we later learned was called the “short arm” inspection, got dressed and went to meet another nice man, the Sergeant Major who was going to teach us drill and marching. At this point they hadn’t let us touch a gun, they didn’t want to complicate things for us.

Our first encounter with the parade ground and the Sergeant Major was terrifying. All this bloke did was scream at us, he wasn’t shouting but actually screaming, his face was bright red and it was obvious that he hated us and was very angry. We couldn’t even tell what he was saying and he had a squad of whippers-in, sergeants and corporals who moved amongst us and set us right when we turned the wrong way. It was a shambles even though we were all trying but the funny thing was that after about two weeks we quite enjoyed parades and drill, it was mind numbing but comfortable in a strange sort of way, all you had to do was stay alert, obey the orders automatically in a smart and soldierly fashion and it was a piece of cake. Of course, this was what drill was all about, part of the brainwashing process to turn you into an automatic killing machine. The bottom line was that you had to obey orders efficiently and keep your nose clean. The last thing they wanted was deep thought.

They soon sorted us out into platoons, we were Gaza Platoon, named after some battle the Cheshires had once distinguished themselves in. The process of breaking us down welded the platoon into a homogenous unit. We were all in the shit together and developed a solid front to the rest of the world. True, there were some who didn’t fit in and their lives were made a misery, not only by the training staff but by us because any individual failure attracted group punishment. We instinctively knew that in unity lay strength and ultimately, survival, so anyone who damaged this was our enemy as well. This was just what the trainers wanted so they did nothing to stop any discrimination in the barrack room. The end result of this was that some blokes were broken and simply vanished, they would be transferred to somewhere else and given another chance or simply re-graded medically and slung back into Civvy street. We didn’t know this at the time of course because this knowledge of the workings of the system would have given us an escape route and at that point we all wanted one.

Re: National Service

Posted: 16 Feb 2019, 09:14

by Whyperion

Tizer wrote: ↑13 Feb 2019, 16:21

Something along the lines of National Service between school and the next stage would be beneficial and it doesn't have to be aimed at providing a military force but designed to get youngsters away from home and into a strictly controlled environment. Personal development and team building with plenty of outdoors activity. There's a lot of work to be done on the environment and infrastructure of the UK.

I'm wondering if this National Service part needs spliting off into its own thread, I have some interesting photos of my father's experiences.

I suppose in 1954 there was still seen the possibilities of a potential agressor that conventional forces would be needed for - any hopefully suitable persons for appropriate special duties would be identified as well. For present day 16+ lads I am reminded of some kind of African documentary where lads were sent off at a teenage year for a year or so to live in the jungle/savanna basically to learn to hunt, and survive on their own, this tribal tradition becomes lacking in the urban (and western) present cultures and one notices how effectively the 'skills' of survival seem to get applied to criminal/anti-social behaviour- it is mainly a male thing, but there are things like the DofE Award schemes etc, but they dont seem to get promoted in society widely enough.

Re: National Service

Posted: 16 Feb 2019, 09:48

by PanBiker

Whyperion wrote: ↑16 Feb 2019, 09:14

I'm wondering if this National Service part needs splitting off into its own thread, I have some interesting photos of my father's experiences.

I was thinking the same as it may turn into a rich seam. I think I will make it so.

I cant move your original comments with the pictures in the other thread Stanley as they would appear out of sequence. You can re-insert them with the comments at a convenient point in here.

Re: National Service

Posted: 17 Feb 2019, 04:15

by Stanley

Ill do what seems appropriate Ian..... let's see how popular the topic is!

One bizarre segment of our indoctrination was a lecture by the Regimental Padre who explained to us that the admonition “Thou shalt not kill” which we had all learned in the Ten Commandments didn’t apply if the target was foreign. This interesting demolition of the concept of the brotherhood of man was reinforced by examples such as “Look at this way, if you found a man raping your mother you’d be justified in killing him.” It was all right for us to kill, maim and destroy as long as it was ‘The Enemy’ we were doing it to and we’d be told who ‘The Enemy’ was when the time came. Above all we had to remember that God was on our side! As a corollary we were told was that it was all right to do anything as long as it was contained in an order. Of course I didn’t buy this but the alternative was conscientious objection and as we weren’t actually being asked to do any murdering at the time it seemed OK to go along with the Padre just for a quiet life, again, this was the intention. You can’t have a soldier who won’t kill when told to so you have to overcome any psychological barriers there are to him doing it. Any previous indoctrination by religion had to be selectively erased. After fifty years reading history I am certain that this indoctrination lecture hadn’t changed since at least 1900. It was a cynical and manipulative ploy to undermine any thoughts we may have had about compassion, in the army’s eyes, this wouldn’t work.

[Interesting that the army used the old Roman Catholic term 'father' for the priest, it's still the convention. The padre had a good precedent for invoking murder and again it is an RC concept. In 1095 when pope Urban II called for a Crusade to kill non Christians he had this same problem, Thou Shalt Not Kill. He solved it by promising that anyone who went on the crusade got a get out of gaol free card in the shape of an Indulgence'. A signed document from the pope saying that they would not go to hell for murder. From that point on indulgences were sold to anyone who could afford them and this was one of the triggers that set Martin Luther off and led to the Reformation.]

One of the good things about training was the emphasis on being clean, well shaven, smartly dressed and polite. We soon learned the basics of polishing boots, ‘blancoing’ webbing (Blanco was the trade name of the proprietary treatment we used on our webbing to keep it clean and coloured light green. In the old days it was done with pipe clay), ironing shirts and uniforms and having a clean shave in ten seconds flat. Apart from free time in the evenings which was largely spent polishing boots, badges and ironing denims or uniforms for the next day, the worse thing about training was everything had to be done in a rush. You never had time to think, you always had to be somewhere dressed in different clothes than the last task and so there was a mad dash to change and get fell in ready for whatever came next. We soon became expert quick-change artists with very shiny boots. For some reason they were called ‘ammunition boots’ and were well-made chrome leather black boots with leather soles and a standard pattern of hob nails. Officer’s boots were brown and better quality. Some of people with large feet were issued with officer’s boots and had to spend extra time making them black with ‘Radium’ leather dye. Boots always had to be clean, well-polished and the toecaps brightly bulled. This was a process whereby you applied successive layers of polish and rubbed it in with small circles with a yellow duster which you spat on. This hardened the polish and enabled a mirror finish, the origin of the phrase spit and polish. All buttons, badges and brasses had to be gleaming and we soon found out how to use our button stick. In case you’re wondering, it was a piece of brass or compressed resin about six inches long with a slot down the middle. You slid your buttons into the slot, gathering the material of the garment up behind and then you had a row of buttons that could be polished with Brasso without soiling the garment.

My button stick. It got polished at the same time as the buttons and even though it hasn't been cleaned for 64 years you can still see the shine!

Re: National Service

Posted: 18 Feb 2019, 04:54

by Stanley

One day they put rifles into our hands and things became interesting for a change. We were taught how to strip them down, clean them and, most important, aim them. (A soldier should be like his rifle. Clean, bright and slightly oiled.) We learned the function of the oil bottle, pull-through and 4x4 flannel which lived in a small compartment in the rifle butt under a hinged brass cap. The rifle was also introduced to the parade ground and we had to learn complicated things like shouldering, sloping and presenting arms. We couldn’t see quite what this had to do with killing people but by this time we were all convinced that the best route to a quiet life was to do as we were told.

Once we had guns we were qualified for Guard Duty. This was a ceremonial guard at the entrance to the depot. The guard had to be turned out in best battledress and boots and be absolutely immaculate. When we paraded for guard we were inspected by an officer and he selected the ‘Stickman’. This was an honorary promotion and was keenly contested because the Stickman went back to billets and had a nights sleep, all he had to do was be on parade the following morning when the guard fell out. I think I got Stickman once but I’m not sure.

I got Stickman once more in 1954 at Gatow.

Eventually the day came when we were put into 3 ton lorries and driven down to Sealand Ranges to actually shoot at something. We all practised with the rifle and the Bren Light Machine Gun. Both these guns used the same ammunition .303 ‘ball’, modern army rifles and machine guns use a far lighter cartridge, .22 and I often wonder how they would cope with the heavier recoil of the .303. We soon learned to respect the quality of the Short Lee Enfield Rifle and the Bren and their effect when they hit something. We got some training with the Sten gun and this took me back to our war-time escapade in the back garden at Norris Avenue.

A word or two about the Sten gun wouldn’t be out of place. At the beginning of the war we were short of automatic weapons and what was wanted was a light, cheap automatic gun for use at close range. The Sten design was simple and brilliant, it could be made out of low grade materials and was almost a throw-away weapon. It wasn’t accurate, but then it didn’t need to be, it was intended for use at close quarters where you could hardly miss. Using 9mm rim fire ammunition it did the job either on single shot or automatic. It was at one time standard equipment for Dispatch Riders (Don Rs) who rode their motor bikes with the Sten slung across their back. They soon found out that it was a mistake to travel with the magazine on the gun because if you went over a bump on the road, the breech block could recoil past the magazine and on its way back up, pick a round up, shove it up the spout and fire it. The usual consequence of this was that the Don R got the back of his head blown off.

After a couple of outings to Sealand, we had to shoot our qualification. Your level of pay depended on your qualifications and one which gave you a pay increase was to shoot a near perfect course on the range and be qualified as a Marksman. This was quite rare and none of us really thought we could get it. Remember I was graded C3 because of my eyesight. On Sept 1st 1954 we shot the course and I scored 101 (Marksman) with the rifle and 168 (First Class) with the Bren. This gave the powers that be a bit of a problem because here was a bloke graded C3 because of his eyesight and he’d produced the only marksman score in the intake, there was more than a suspicion that there had been a bit of help. Down in the butts where the targets were, there was a party of blokes, often your mates, marking up the scores and pasting patches on the targets. In theory, they didn’t know who was shooting at what but the army knew that we were cunning buggers and they also knew that it was just about impossible to tell the difference between a hole made by a .303 bullet and a lead pencil! There was some scepticism about my performance. The following day, the Sergeant Major told me to draw my rifle and he drove me down to the ranges by myself. I was set up on the range and made to shoot the course again. I scored one better than the previous day, largely because of the weather. The SM asked me how come I was graded C3 if I could see like that and I told him that I was just about blind without my glasses but could see perfectly well with them. I could only suppose I was graded on my unaided vision. Anyway, they gave me my Marksman badge on the basis of my original score and I have to admit I was very proud to sew it on my sleeve. Father thought it was a bit special as well which was nice, perhaps it was Old Alex’s genes poking through because he was a remarkable shot.

I've lost my marksman badge but here's what it looked like.

Re: National Service

Posted: 18 Feb 2019, 09:53

by Tripps

I came across this a few days ago, and put it in my 'cuttings' folder. I split it into verses, and it made more sense.

I've heard of a 'stickman' who was carried on a chair from the barrack room to the guardroom on a chair so that his boots wouldn't get scuffed on the way. I never bothered even trying for it - hopeless cause. Easier to do the duty.

Poet - Henry Reed

Today we have naming of parts. Yesterday

We had daily cleaning. And tomorrow morning,

We shall have what to do after firing. But today,

Today we have naming of parts. Japonica

Glistens like coral in all the neighboring gardens,

And today we have naming of parts.

This is the lower sling swivel. And this

Is the upper sling swivel, whose use you will see,

When you are given your slings. And this is the piling swivel,

Which in your case you have not got. The branches

Hold in the gardens their silent, eloquent gestures,

Which in our case we have not got.

This is the safety-catch, which is always released

With an easy flick of the thumb. And please do not let me

See anyone using his finger. You can do it quite easy

If you have any strength in your thumb. The blossoms

Are fragile and motionless, never letting anyone see

Any of them using their finger.

And this you can see is the bolt. The purpose of this

Is to open the breech, as you see. We can slide it

Rapidly backwards and forwards: we call this

Easing the spring. And rapidly backwards and forwards

The early bees are assaulting and fumbling the flowers:

They call it easing the Spring.

They call it easing the Spring: it is perfectly easy

If you have any strength in your thumb: like the bolt,

And the breech, and the cocking-piece, and the point of balance,

Which in our case we have not got; and the almond-blossom

Silent in all of the gardens and the bees going backwards and forwards,

For today we have naming of parts.

Re: National Service

Posted: 18 Feb 2019, 11:59

by Tizer

That's brilliant, Tripps, thanks for posting it!

Stanley, I'm enjoying all this and look forward to hearing about what grub they gave you and how you got along with the cooks.

Re: National Service

Posted: 18 Feb 2019, 14:15

by Stanley

I know the poem well David and yes we did have to name the parts, what's more we had to do it later for the 17pdr.

I never saw a stickman carried to the guard but we were always very careful, especially of scratching the toe caps on the best boots which were like mirrors! I don't understand how that could have happened actually because until the officer inspected the guard you didn't know who the stickman was.

Glad you're enjoying it Tiz.....

Re: National Service

Posted: 19 Feb 2019, 03:34

by Stanley

The rifle wasn’t just useful for shooting with, we all had a bayonet, in effect, a short stabbing sword which clipped on the end of the rifle barrel. It was meant for use at close quarters and we were trained to attack and kill the enemy with it. We soon learned that the bayonet didn’t work if you weren’t screaming like a banshee. They also taught us how to kill quietly with bayonet and strangulation and gave us a grounding in unarmed combat and various other nasty ways of killing and maiming people. (Always slide the blade in an upwards direction, it gets through the ribs easier that way.) Writing it down like this 45 years later it seems far-fetched but it was a different age and we were the next generation of cannon-fodder. Funnily enough, as I march steadily towards 80 years of age it amuses me to think that the hard case young men we all come across these days fuelled by testosterone and combat knowledge gained from computer games have no idea that the old bloke walking his dog is licensed as a deadly weapon in Stockport! I often have a quiet chuckle…

On a less aggressive note, but equally unpleasant, they exposed us to gas in sealed rooms and demonstrated how the gas mask could save our lives. We were taught how to move quietly either upright or on our bellies and how to use camouflage to render ourselves less visible. As a grand finale we went on a ‘night scheme’ where we played war games and were fired at with live ammunition just to get us used to it. We found out that all you hear is a snapping sound as the bullets pass you.

Our six weeks was almost up. We knew we would be posted to the battalion but didn’t know where they would be as they were just arriving back in the UK after a tour of duty in Egypt. Our next landmark was the passing out parade and by this time our mothers wouldn’t have known us. The training was hard and the worst ten weeks I ever had in my life but it did have its compensations, we were different men than the youths who had come through the gates in June. Mentally we were all changed, we were a lot harder and our attitudes towards death and violence had been changed, perhaps for ever. I don’t think we realised this at the time but it was so.

We had one piece of light entertainment while we were at the Dale. We were informed one weekend that we were all detailed to act as marshals at an air display nearby. This was a day out, a complete change and off we went on the Saturday to an RAF airfield in Cheshire, I’ve tried to remember the name of it but it completely escapes me. The Saturday passed without incident, all we had to do was stand in front of the ropes holding the crowds back and make sure nobody encroached on to the airfield. Sunday was to give us all a bit of a shock. Just before lunch there was a display by a flight of Meteor jets. Remember that in those days, a jet propelled aircraft was like rocket science to us, we very seldom saw one. These lads put on a really good display and went into a manoeuvre where they followed each other in line astern and dived down from a great height, flat out as it seemed to us, and pulled out of the dive very close to the ground before going into a loop and diving down again on to the airfield before roaring off straight and level into the distance. All went well until one of the planes failed to pull out after doing the loop and plunged straight into the ground about 600 yards away. He never knew what hit him because they reckoned he had blacked out because of the G forces during the loop, these things weren’t properly understood then. What made it worse though was the fact that the pilot’s wife and children were stood on the ropes just behind me and of course, it was a terrible shock for them. This brought the display to an end and we went back to barracks. The interesting thing to me about this occurrence is that it didn’t really upset us. I shall speak more about this later but I think we all had scar tissue from the war. Death, particularly violent death, didn’t affect us as much as it would today’s generation of our age. We were, to a large extent, hardened to death and of course, all the training we were going through reinforced this.

I’ve remembered that there was one more excursion. The word went out one day that anyone with farming experience should report to the company office. About three of us went and found ourselves doing three days on some threshing tackle to help a local farmer out. The army made a big thing about this and we hit the headlines in the local paper. Light entertainment for us and a nice change because nobody was shouting at us.

Light entertainment......

Re: National Service

Posted: 20 Feb 2019, 06:46

by Stanley

Towards the end of training we had an open day for parents and whilst I can’t remember mine coming I can remember at was a good day. There were demonstrations of firing guns and an open competition in the indoor .22 range which we didn’t know existed, we had never used it in training. I think it was about 50 yards and you got ten .22 rounds to fire through a standard Lee Enfield with a modified barrel. It was very popular with the visitors and we were allowed to have a go as well later in the day. I can remember there being a dispute about my score because I had put all ten through the bull and there was just a ragged hole. I don’t think they allowed it because there was a small prize and it was a winning score.

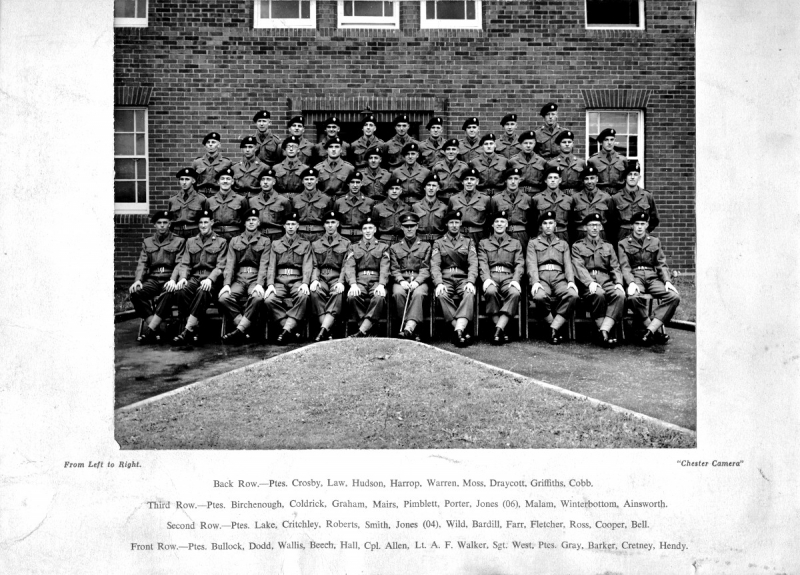

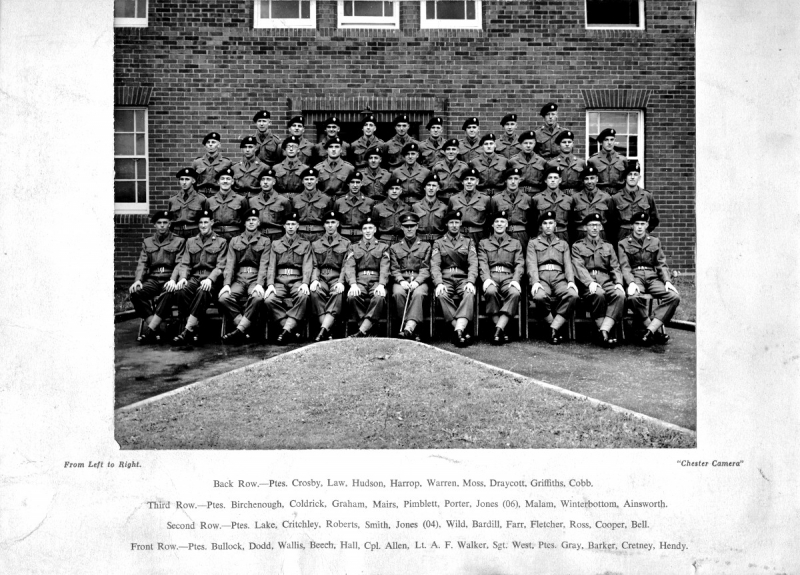

Gaza Platoon in 1954, almost ready for passing out. [Just before I went in to hospital we had the passing out picture. Say what you like, we were a smart bunch of lads. If nothing else they had got us all into the habit of polishing boots, note the mirror-finish toecaps on the front row.]

I was to be cheated of my moment of glory in the passing out parade. Shortly before the day I developed an abscess under an impacted molar and was taken into the military hospital at Chester where they operated on me. It was regarded as a fairly serious operation then and it took me a fortnight to recover. I think the anaesthetic did as much damage as the knife, it took me three days to recover from it. We were well looked after and the main thing I remember is that we had the choice each evening of either having a mug of Ovaltine and a biscuit or a bottle of Guinness, guess which I went for! Father came down for me and my kit and I went home for a fortnights end of training and convalescent leave before joining my mates in Lichfield Barracks where we were warehoused until the Battalion had settled down in their new quarters at Meanee Barracks, Colchester.

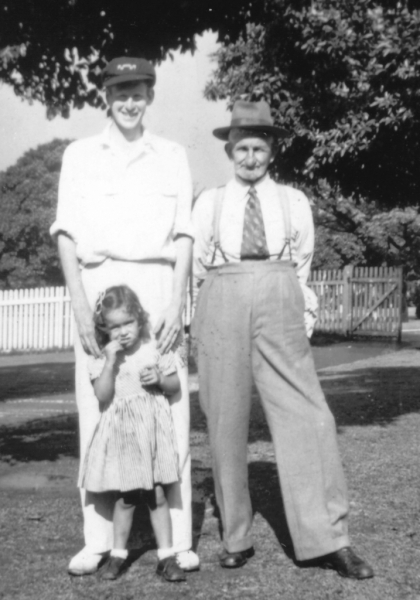

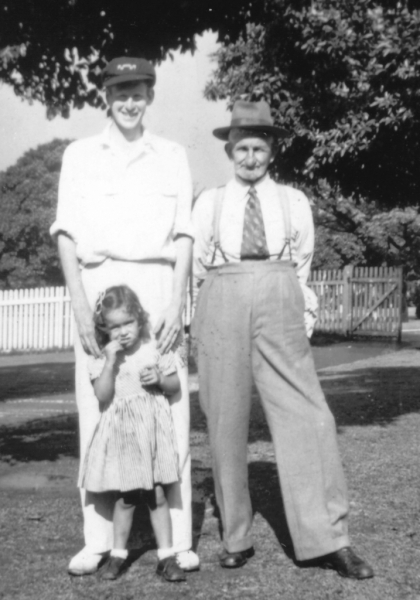

With Dorothy on convalescent leave in 1954. Note that even though I was passed out as a trained soldier I haven’t got any collar dogs in. These were small acorn badges in each side of the collar and you didn’t get these until you actually joined the battalion.

The Barracks at Lichfield were a disgrace. I think they were actually redundant quarters for the Staffordshire Regiment and one block had been opened up for us while we waited to go to Colchester. They were typical mid-nineteenth century army barracks, absolutely unchanged since they were built and incredibly gloomy. I think that anyone who had ever been in a Victorian workhouse would have been instantly at home. Each floor of the block was one large room with rows of beds down each side, a cast-iron bunker full of coke, a large open fireplace and that was it. It was the end of September and starting to get cold but we were not allowed fires as according to the army the heating season hadn’t started. I don’t think they really knew what to do with us so the Non Commissioned Officers (NCO's) who were with us just set us on to cleaning everything. For about six weeks all we did was parade and bull the place up. Cleaning was always called bullshit because it was said to baffle brains. The motto was ‘If it moves, salute it, if it stays still paint it white.’ The only entertainment on the camp where we were confined to barracks was the Church Army and I have to report it was not the most cheerful establishment I have seen. One day we were all paraded with full kit, loaded on to wagons, taken to the station and shipped down to Colchester to join the real army, the battalion.

When I came away from The Dale I was allocated to the Assault Pioneers. Some explanation is needed here. An infantry battalion is divided into companies and the companies into platoons. The actual foot soldiers were in companies designated with a letter of the alphabet, A company, B Company etc. I think we had four of these. There was a headquarters company which comprised all the battalion administration and another which was called Support Company. The latter consisted of four platoons, Machine Gunners, Mortars, Assault Pioneers and, best of all the Anti-Tank platoon. These were all specialist platoons and had extra training. Machine Gunners manned the Vickers medium machine guns which were the battalions main killing weapon. Mortars were equipped with the Three Inch Mortar, an incredibly simple weapon but capable of putting down enormous weights of explosives at long range. The Assault pioneers were the demolition experts and tunnellers. Anti-Tank platoon manned four Seventeen Pounder guns which were a splendid piece of kit. Somewhere between the Dale and Colchester there was a change of plan. I was allocated to Anti-Tank which in itself was great as far as I was concerned, it was what I wanted to do, but in terms of my grading meant I had the satisfaction of having seen the army cock up as comprehensively as it could. They had graded me C3 (unfit for infantry or artillery), put me in the infantry and excelled themselves by getting me into artillery as well! Well done lads and definitely par for the course.

At Colchester while the infantry companies were in Victorian barracks much the same as those at Lichfield we were billeted in Spiders. These were WWII wooden huts which were warm and comfortable, there are worse places to sleep than a good wooden hut! The barrack rooms were smaller, about 18 to a room and we were kept together as gun crews. This meant I was living with the group I would be with all my army life because crews were never split up unless it was absolutely necessary. In every sense of the word it was a family and I took to it like a duck to water. As usual, there was a downside and it was called the Company Sergeant Major, Ted Talbot, we used to call him Terrible Ted and he had the capacity to make our lives a misery. In his defence, he was a soldier through and through and was competent, if ever things had got sticky we could have relied on him but this didn’t mean we had to like him. The only time I ever saw him laugh was when a lad called Doyle did a brilliant impersonation of him at the Christmas do we had at Colchester. Perhaps he had a human side and was fond of kids, if so he took good care we never saw it.

Re: National Service

Posted: 21 Feb 2019, 04:56

by Stanley

One word about these dyed in the wool soldiers, the word we used to describe them was ‘regimental’ and amongst us NS men it was a matter of honour to avoid taking on the ethos to the extent we could be described as such. I later realised that there was a good basis for this. Immersing yourself in army life for twenty two years was the equivalent of being in gaol or a mental institution in many ways. The army did everything for you and when you left you were adrift and had to learn the skills necessary to support your own sky. I have seen this happen and it’s not pretty, being ‘institutionalised’ is a handicap and I don’t think the army has properly addressed this even in the 21st century. It says a lot for us young lads that we instinctively recognised this, another life lesson well learned!

When I first got to Colchester we had a temporary platoon sergeant who was a bastard. He had a nasty habit of crapping in wash basins when he got drunk and making us clean it up. I’m certain that it was him because I was going on about it in a loud voice one day in the barrack room, The sergeant’s bunk was in a partitioned space near the door and we thought he was out. He came out and glared at us and had obviously heard every word but simply walked away. Believe me, if he had been innocent my feet wouldn’t have touched the ground on the way to the guard room! He left us shortly after I arrived and joined the regimental police, more of him later. His replacement was Sergeant Edward Lancaster.

Ted was a cracker, he made us do all we had to but in a way which made us glad to do it. Hard to explain but he had the knack of commanding without ordering if you see what I mean. I think I learned a lot from Ted about man management and under his efficient but benevolent care we settled down to life with the battalion. He was to be with us right through my service and we were very lucky to have such a good man. There were regular passes out into the town and we had interesting things to do like learn about the guns and how to care for them. Ted was actually an old machine gunner, more about this later.

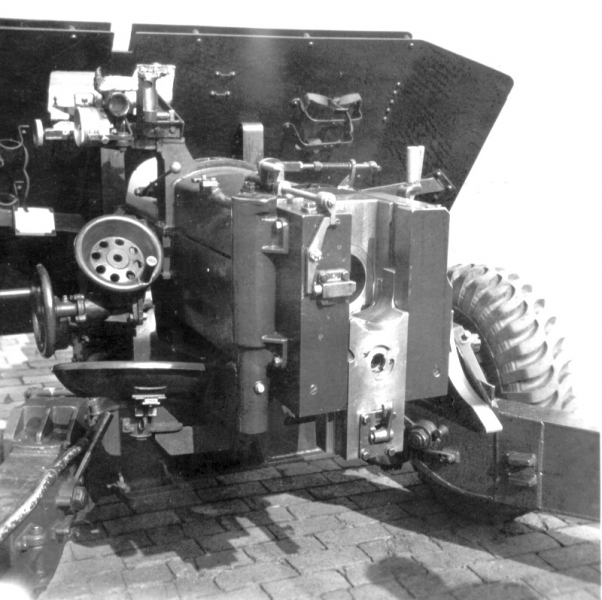

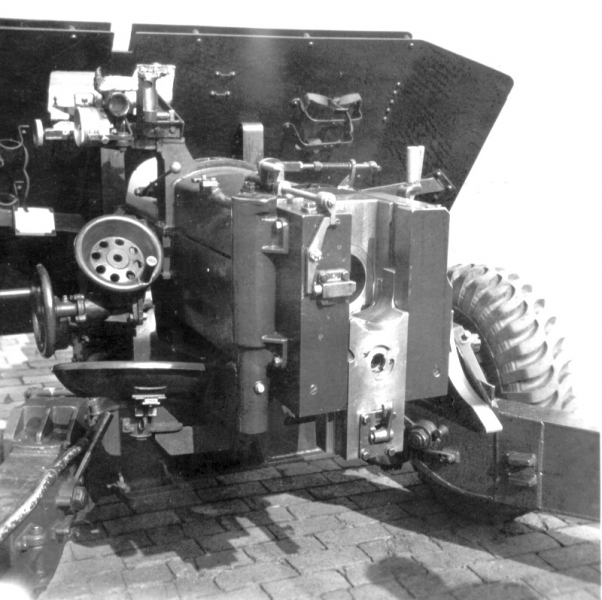

The 17pdr pounder anti-tank gun was the last in a long line of conventional anti-tank weapons. Having seen war service Ted knew about the shortcomings of the early weapons and he filled us in on the history, not part of the official training of course but typical of Ted, he gave us the background. The standard 25lb artillery gun had an anti-tank role but the infantry needed something more mobile. In 1937 the Boys anti-tank rifle was introduced. Basically it was a high velocity rifle mounted on a tripod that fired a .55” tungsten cored round which would, with a bit of luck, penetrate ¾” of armour plate. With the rapid improvements in tank armour this was soon an obsolete weapon so the army developed a small calibre high velocity artillery gun which could penetrate the skin of most contemporary tanks and armoured vehicles, the 2 Pounder anti-tank gun. It was designated 2pdr because the armour piercing round weighed two pounds. As armour improved it was upgraded to the 6 pounder which was essentially the same but larger. Faced with the German Tigers and the possibility of having to deal with the Russian T34 and JS3 tanks the army took a leaf out of the German book and produced a weapon to match the brilliant Krupps designed 88mm. The 17pdr pounder was 77mm bore but almost as hard hitting. Unlike the 88mm and its American counterpart it had no anti-aircraft role and was thus a simpler weapon to use. It could fire a variety of ammunition including High Explosive (HE). Each gun weighed 3 tons and was towed by a Stuart gun tower which was an ex. US Army Stuart Light Tank with the turret taken off. These had rubber shod tracks, two Cadillac V8 engines and Hydramatic drive. It was the heaviest equipment the battalion had, about twelve tons of armour plate which gave reassuring shelter! We were kings of the road and we knew it.

Late in the war the most successful American tank, the Sherman, was fitted with the 17pdr and soon got nicknamed the ‘Firefly’. This was because of the incredible speed of the round between gun and target. Each round had a bright red tracer in the base and at night they looked like giant fireflies. I have since looked into tanks and tried to understand why we were so very badly prepared for WW2. Apart from being too lightly armoured and under-gunned our tanks had other faults. For instance, our main battle tank, the Cromwell could only do 2mph in reverse, not a lot of good if you wanted to get back into cover quickly. They had petrol engines as well where the Germans favoured diesel. The problem here was that one hit from an 88mm and our tanks brewed up, they became a mass of flame. The Germans called them ‘Tommy Cookers’ while we called them ‘Ronsons’ after the petrol cigarette lighter. The Germans had realised that it was a lot harder to penetrate sloping armour and put glacis plates on the front of their Panzers which deflected a head-on shot. We built the Cromwells with a flat front. What fascinated me was how come we had been so slow and inefficient? By the way, you might wonder why I still searched for answers years after I left the army, remember that tank-killing was my trade and I still have the skill. Like many other tradesmen I still keep up with developments even though I am not practicing my trade any more.

Barrel number 23027. I stayed with this gun for the rest of my army career.

Re: National Service

Posted: 21 Feb 2019, 08:58

by plaques

One of my lecturers was in charge of a tank repair base during the war. He never did declare his rank but it became obvious he was the top man. Everything in his lectures always had an element of tank design or some practical application. Not someone who would let theory get in front of the actual use, one of his examples was a salesman who wanted to supply a new heavy lift Jack for lifting tanks. "This is latest compact jack rated at 50 tons and will lift any tank under field conditions" was his opening claim. "No it won't" was the reply. Pressing his point the salesman continued with. " whats your heaviest tank, this will lift it no problem". "OK lets go out into the yard for a demo. lift the front end of than one". The jack now placed in position started to lift but promptly sank through the concrete into the ground. "Your jack's base isn't big enough, come back when you've got it sorted". A practical demonstration is worth a lot more than a load of 'it should' statements.

Re: National Service

Posted: 21 Feb 2019, 09:39

by Stanley

I can identify with that P. One of the things that I liked about the 17Pdr was that in the ten years the army had been using it (1944-1954) they had sorted all the bugs and the gun and the associated equipment that went with it were all eminently fit for purpose. Apart from the accuracy, which was superb, it made it such a practical tool. That was how we were taught to view it, especially by Ted Lancaster. He knew that if we ever went into action, not only had we to be well trained in management and use, we had to have full confidence in the equipment. He certainly infected me as we'll see later.......

Re: National Service

Posted: 21 Feb 2019, 13:02

by Tripps

plaques wrote: ↑21 Feb 2019, 08:58

Immersing yourself in army life for twenty two years was the equivalent of being in gaol or a mental institution in many ways.

Not if you were aware of things, and acted accordingly.

'They' told me I was mad to join - now it's the equivalent of 'being in a mental institution'

I take some comfort in the pension - which I have been in receipt of since about 1985.

Re: National Service

Posted: 22 Feb 2019, 04:47

by Stanley

True David but some were damaged.....

I dug deep and realised that the deficiency in the hardware was a symptom of a gross deficiency in army thinking. It’s said that all armies plan on their experience of the last campaign. When the tank was invented by the British in WW1 it was regarded as a mobile pill box, a protected fire point that could move forward with the troops, in other words, a mobile trench. One man saw the flaws and advocated an entirely new strategy, the use of the tank as a spearhead weapon to break lines and gain ground supported by infantry. His name was Brevet Colonel J. F. C. Fuller and after the war he was on the War Office staff promoting his ideas. Apart from the fact that he was dealing with a hidebound organisation, he had a further handicap. He was a disciple of Aleister Crowley, ‘The Great Beast’ who openly advocated Satanism as a religion. As soon as this became known his ideas were ignored, he left the War Office and later joined the British Union of Fascists. The irony is that had Oswald Mosely triumphed, Fuller would have been minster of defence and perhaps the course of history would have been different.

Fuller’s ideas hadn’t fallen on deaf ears abroad. His papers were studied in Russia and Germany and it is no coincidence that Heinz Guderian and others evolved the principle of ‘Blitzkrieg’ in which fast moving armour was the spearhead which drove into the heart of a territory. This dichotomy of ideas is what led to our miserable armour and anti-tank capability in 1939. It’s worth mentioning as well that neither the British or American armies had a light machine gun to equal the Spandau LMG or a weapon like the 88mm. These deficiencies cost us dearly right up to the end of WW1. In the fight for Normandy the Panzer VI, the Tiger, and the 88mm A/Tank gun were still the dominant weapons in the tank war.

My training went on apace, it was easy to learn because I was working with men who had been with the guns in Egypt. They knew their job and passed on knowledge willingly within the family. Also, being a specialist platoon we had our own REME gun fitters, ‘Rich’ Richards and Taff Rees. Rich was a regular and had spent all his service on 17pdrs and was a mine of information. Our days were spent cleaning the guns and towing vehicles, maintaining stores and doing gun drill. We didn’t do any where near as much square bashing as the other platoons in Support Co largely because Ted was a bit overweight and avoided it whenever possible.

I spent a lot of spare time in the stores with our platoon storeman Bert Hollingworth who was a lot older than us but was still doing national service. He shared with another Stockport lad, Bernie Simms who was a sort of general company dogsbody. He painted signs and did a bit of decorating. Bert was a carpenter in Civvy street and came from Poynton just north of Hazel Grove. He had a coke stove which we used to get red hot to cook little treats and brew up. Bert slept in the stores sharing with Bernie and they had the best billet in the camp. We spent many happy hours in there smoking and yarning and working out what we would do when we got out. All NS men had one thing on their minds and when you met someone the first question was always “How long have you got to do?” We all had a demob chart on the inside of our locker door. It was a two year calendar and every day you marked off one square and watched the two years slowly get blanked out. I can’t tell you how important that bit of card was to us and most of us kept the same one all our service.

An interesting and significant thing happened one day. We had gone down to the Motor Transport Pool in the camp to bring back one of our Stuarts which had been in there for a service. We found it was blocked in by an Antar tractor and low loader. This was a tank carrier and was the largest motor vehicle the army had at the time, it was powered by a Rolls Royce Meteorite V8 petrol engine and could run at 100 tons all-up weight. We looked for a driver to move it but it was NAFFI break and there was nobody about. We were in a hurry so I did the obvious thing, I jumped in the bugger and shifted it. It was big and I had to squeeze it back into a corner of the yard so it was out of the way. As I jumped down a voice shouted from the window of a hut across the yard, it was Captain Kingdom, the battalion MT Officer. With my heart in my boots I ran across the yard, pulled up at attention in front of the window and saluted as he had his cap on. “Have you got a qualification for that vehicle?” No point in lying so I told him no. “Where did you learn to drive like that?” “Taught myself Sir” He told me they were waiting for a driver to be sent up from the local supply depot because none of his drivers was capable of moving it. He gave me a piece of paper and for one horrible moment I thought it was some sort of disciplinary action but when I looked it was a certificate to say I was ready for my driving test.

He went round and had a word with Ted Lancaster and that afternoon an MT sergeant took me out in an Austin 15cwt truck, had me drive him around the Essex countryside for the afternoon, this included a couple of stops while he had a pint, and on our return took me into the MT office where Captain Kingdom gave me a pink slip. I asked him what it was and he told me to take it to the local licensing office and they would give me a full licence. He was right, I got it and that’s the only driving test I ever did.

Thorneycroft Antar transporter.

Re: National Service

Posted: 22 Feb 2019, 19:32

by Tripps

It wasn't all 'beer and skittles'. but sometimes it was.

Somewhere South of Rome 1971

30927504637_d36d11b4df_n.jpg

Re: National Service

Posted: 23 Feb 2019, 03:24

by Stanley

We were all so young then......

We had been hearing rumours for a while about a new anti-tank gun. The gun itself wasn’t secret but the principle it worked on and, more importantly, the ammunition, was very hush-hush. This was the Battalion Anti Tank gun, BAT for short. Great excitement one day when a low loader turned up and we took delivery, I was taken off the 17pdr and put on the BAT crew and we started by cleaning the thing until it gleamed and then took a quick course of instruction from a visiting sergeant from Larkhill on Salisbury Plain where the army had its gunnery school. We weren’t the only ones, everyone was trained but we found out why we had been dedicated when word came through that we were to load all the guns and towers on a train and set off for Larkhill where we were to fire the 17pdrs and do some test firing with the BAT. Deep joy!

The BAT 150mm just after firing at Larkhill on Salisbury Plain. All pictures of heavy guns firing are blurred. Don’t criticise the quality, it’s the concussion of firing which moves the camera.

Before you start saying so, you’re right, this was genuine big boy’s toys country. There is nothing quite like firing heavy guns and doing massive damage to thick armour plate. Once on the ranges we had a wonderful time. We zeroed the 17pdr gun sights and test fired them at targets, then we fired at scrap tanks which were dotted about the ranges at various distances. We all swapped jobs on the guns and I can’t tell you how satisfying it was to aim and fire a couple of rounds at a tank 1200 yards away and hit it full on both times. The noise of the guns was incredible and the concussion when you fired shook every bone in your body, the stones on the ground danced with the shock. When the solid armour piercing round hit the tank there was a flash and a big cloud of red dust which was the rust flying off. The beauty of the 17pdr was that it was such high velocity that the trajectory of the round was almost flat. If you pointed it right and the range was somewhere near accurate you hit it. From a gunner’s point of view it was a wonderful weapon.

Then, the BAT crew had their moment of glory. We were lined up and given a lecture by a bloke in a civilian suit. He explained that they had been having ‘some problems’ with the ammunition. I should explain here that the chief virtue of the BAT was that it was recoilless, in other words, it didn’t need complicated hydraulic buffer systems to absorb the shock of hurling a round at incredible speed so it could be made twice the calibre of the 17pdr but only half as heavy.

The way it worked was this, the ammunition for the 17pdr was like a big rifle cartridge, it was built exactly the same way. The propellant charge was held in a brass cartridge case and was initiated by a percussion cap in the base. The 17pdr shot itself was jammed in the end of the brass cartridge so when it was pushed into the breech and the breech block was closed, any gas from the explosive had only one way to go which was to go up the spout and shove the armour piercing shell out at incredible speed. It got its penetration from the large amount of explosive in the case and when it went off it was like a gigantic whip cracking.

The BAT was different. The ammunition was much larger (150mm) and the cartridge case had a plastic end cap instead of solid brass. There was no percussion cap, the primer was fired electrically by a high voltage current through the rim of the cartridge. The gun was different as well, there was a conventional breech block but it had a hole through the middle about four inches in diameter and a funnel shaped venturi mounted over this hole. When you fired the gun, four fifths of the force of the explosion escaped out of the venturi and the other fifth drove the round up the barrel. This meant the round was fairly low velocity but much heavier. The gun hardly moved when it fired. The parlour trick was to put a glass of water on top of the shield and it never spilled, quite amazing.

Anyway, back to this bloke and his ammunition. He told us that unfortunately they were having trouble in that the rounds didn’t always go off. Technically this is what is known as a hang fire. This is the last thing you want because there is a good chance that the train of combustion has actually started and the round can explode at any time. Obviously, the longer you can leave the gun if you get a hang fire the better but the army in its wisdom had decreed that unless in active service, about twenty minutes was about right. The other thing he warned us about was the back blast. When the gun was fired a flame thirty feet long came out of the venturi and anybody stood in the way was a goner. With that he wished us luck and told us to fire five rounds. Somewhat less enthusiastic, we went into our drill. I should say that we were encouraged by the fact that Ted stood beside us while we did it. He wasn’t going to desert us in our hour of need.

We fired the first three rounds with no problem at all. The only thing that bothered us was that the range needed to be a lot more accurate as you were lobbing the rounds rather than stabbing them. The ammunition was designed for this, it was High Explosive Squash Head, HESH for short. The idea was that when the round hit the tank it didn’t penetrate but squashed out on the armour forming a shaped charge. The special fuse was mounted in the back of the round and ignited a fraction after the round hit. As the shaped charge went off it either punctured the armour with a jet of hot gas or vibrated a white hot piece off the inside which flew round in the confined space and brewed up.

All this left our minds as we fired the fourth round and there was a deathly hush, just the click of the magneto and nothing else. We went through the drill and fired a second time using the alternative igniter, still nothing. We all crouched there round the gun and waited for someone to make a suggestion. I was right next to the breech block and I whispered to Ted, “I can hear fizzing!” Ted told us to stand fast while he consulted with the brains. He went out in a wide arc away from the gun and approached the brass who were standing there waiting for somebody else to say something. I saw Ted salute but just then there was a dull thud and a roaring started in the venturi and rapidly became the biggest fire work display you have ever seen. A solid jet of flame twenty feet long was roaring out of the back of the gun. The gun started to move forward even though the brakes were on, it was rocket propelled. We just hung on to it and followed. After what seemed an age the flame died down and we all relaxed. All the paint had gone off the venturi but apart from that everything seemed to be OK.

At this point we realised that there was a bit of a commotion going on in the background. We could hardly restrain ourselves when we saw what had happened. The observers had been standing well back and to the side to avoid the back blast but when the hang fire started they had moved closer to see what was going on. When the round burned the gun had slewed and the tail end of the flame had caught the group. The immaculate suit of the ordnance bloke and the expensive uniforms were ruined. It hadn’t done facial hair much good either. In the end they all retreated except the senior officer, a Colonel. “Well, what are you waiting for? Get the dud out and fire the last round”.

Easier said than done, the case was that hot it had expanded and we couldn’t open the breech. We let it cool down while we stood by and had a smoke and eventually got the case out with the shot still on the end of it. We loaded the last one and fired it, no trouble at all. The Colonel came over then and said some nice things to us and we packed up for the day. All our mates had been watching and we had a good do in the NAFFI that night!

Re: National Service

Posted: 23 Feb 2019, 21:32

by Tripps

Thanks for that remarkable account - it's a great piece of writing, we're lucky to be able to read it, though It's not a very good advert for recruiting tank crews.

The word 'blind' brought back a memory of grenade training when if you had one - you had to deal with it yourself. Nice to hear the explosion thud.

Re: National Service

Posted: 24 Feb 2019, 03:21

by Stanley

Thanks David. Glad you're enjoying it!

We went back to Colchester, complete with a slightly used BAT and some misgivings about having to fire it again. Actually, we had little doubt that the brains department would eventually sort out the ammunition but personally, I was more concerned about the trajectory, I could see that we were going to have to be a lot more accurate with our ranging, we had no range finders, it was all done by eye. This isn’t so bad with artillery where you have the luxury of observers and ranging shots but our trade was slightly different, we had to have a hit first time because the act of firing revealed where you were and we didn’t want to encourage incoming mail. We were learning our craft and topics such as this were the subject of many conversations. One thing we noticed with the BAT was that like a very big naval gun, if you are directly behind the gun you can see the shot in flight for a fraction of a second. Mick Burgess once told me he could see a 17pdr round as well but I’ve never managed it.

There was a lot to learn. One of the big problems with the 17pdr was hiding it. We didn’t just drop the gun off the towing vehicle and fire it, though in extremity this was an option which we called ‘crash action’. Our preferred method was to find a good location with some cover and rising ground behind where we would dig the gun into a shallow pit so that only the barrel and the top of the gun shield were visible. We would erect a camouflage net over the top and camp out round the gun with our rations and ready use ammunition. The Stuart would be sent back and hidden hull down, within easy reach but out of harms way. If everything went wrong we needed it for our strategic withdrawal. Digging gun pits was made much easier by judiciously placing five small charges of 808 plastic explosive, one at each corner and one in the middle. This broke the ground and made digging much easier.

Anti tank work was all about concealment and ambush. Ideally you hid the gun so well that you could knock off several tanks before anybody could pick out where you were dug in. This wasn’t easy and we soon became pretty good at selecting the right place, a lot depended on it. There was another problem with the 17pdr, it had an enormous muzzle flash on account of the large charges we used to get the velocity. This was alleviated to some extent by the muzzle brake which diverted a lot of the gas to each side when you fired and incidentally, cut down on the recoil. The problem was that this flame could scorch the earth and leave a signature or even set fire to dry undergrowth and grass. It was as well to bear this in mind as it could be, literally, a dead giveaway.

We spent a lot of time in the training areas around Colchester by day and night, digging in and practising gun drill on our own or, occasionally, doing schemes or war games with the rest of the battalion and the Tank Corps as well who became our enemy. We soon learned interesting things like the fact that if the noise of a tank exhaust increased this was good news as it was turning away from you. If it rained we dug a trench and backed the Stuart over it, they made a good shelter! We weren’t allowed ammunition of course but were issued with thunder flashes to simulate rounds fired. Umpires assessed our performance and decided whether it was a kill or not. They also decided whether we had been detected and deemed destroyed. Everyone had their own job round the gun. As I remember it there was the gun commander who stood to the left side and selected targets and ranges, No.1 was the gun layer, he aimed and fired the gun. No.2 stood behind him, repeated the orders, set the range on the sight and was generally responsible for checking on everything that was happening round the gun. No.3 was the loader who opened the breech using the LBM (Lever Breech Mechanism) on his side of the gun and actually shoved the round up the spout, this automatically closed the breech. When the gun was fired and recoiled on the buffers a cam automatically opened the breech and ejected the empty case ready for No.3 to load another round. Nos.4 and 5 passed ammunition up to the loader. When training we swapped jobs regularly so that we could all do any job. This rotation included the Gun Commander who was always a corporal or lance-corporal.

I remember on one scheme it was my turn to be commander so I was entrusted with the thunder flashes. The only trouble was I’d forgotten to grab them when we piled out to get into action and the Stuart was too far away to get them. We decided to carry on without them and of course, this was exactly the time when an umpire turned up and informed us there was an enemy tank at 400 yards coming straight for us. I shouted all the necessary orders, we aimed and fired and at the point where I should have thrown the thunder flash in front of the gun I simply shouted BANG! As loud as I could. The umpire was taken aback at this and asked why I hadn’t got thunder flashes. I told him the truth and, after bollocking me for having forgotten them he congratulated me on my initiative! Big sigh of relief but for weeks afterwards people were shouting BANG whenever I walked into a room!

Here’s Mick on the left with me and Johno later on at Sennerlager. In case you’re wondering, I had broken my glasses. Notice that we are all wearing collar dogs, we’re proper soldiers now! The shield on the left arm is the Mercian Brigade badge.

Re: National Service

Posted: 25 Feb 2019, 07:39

by Stanley

We had another bit of excitement at Colchester. The gun layer on our crew was a bloke called Mick Burgess, he was a genuine tough guy, regimental boxing champion and hard as nails, he was also, as I found out later, the best gun layer I have ever seen. One day a posse of Military Police arrived and arrested Mick. We were baffled but word soon spread that he had been arrested for desertion from the Green Howards, a rifle regiment. Shortly afterwards he was returned to the fold and told us the story.

He came from Manchester and had had a rough life. He was up in court getting 18 months for garage breaking and the judge told him that the next time he offended it was five years guaranteed. He served that sentence in the same prison as Haigh the Acid Bath killer as I remember. When he was released he decided the best thing to do was join the army, criminal convictions were no bar evidently. He enlisted for 22 years in the Green Howards but when he had been in for a while realised he was in a Rifle Regiment. These were rather special units and the main characteristic was that they did everything at the double with arms at the trail and, being heavily built, this didn’t suit him at all so he deserted and joined the Cheshires, also on 22 years engagement. Going into another regiment was probably the best place for a deserter to hide and he got away with it for about six months but was eventually found out. He was arrested and thrown in the cells at the guard room but was soon back in the fold with us. Nothing ever came of it and we came to the conclusion that the army had made a sensible decision on the grounds that he was a valuable soldier who had simply arranged his own transfer. Of course, the fact that the Cheshires didn’t want to loose a good heavyweight boxer might have had some bearing on the matter! I remember that later while we were in Berlin, I got into trouble in a bar with a very aggressive Argyll and Sutherland Highlander, it was something to do with referring to his regiment as the ‘Sheep Shaggers’ and Mick rescued me from a fate worse than death by simply putting his arm round me and smiling at the bloke. You knew who your friends were and I have very warm memories of Mick, a lovely gentle man, just goes to show that being in gaol isn’t necessarily a good guide to character.

Shortly after Christmas 1954 we got word that the battalion was on the move again. At first we thought it might be Korea and I wasn’t very happy about this, I was too young to die! Eventually we were told that we were going to Berlin and this suited us down to the ground, at that time it was recognised as probably the best active service posting a regiment could have, we got active service pay but with minimal danger. I was to serve out the rest of my time holding back the communist hordes, but first, there was a spot of embarkation leave.

I arrived back home in Heaton Moor a very different lad than the one who had left home to go farming 18 months before. Bill Rae was in the army as well, he was in the Catering Corps and I think I missed seeing him that time. Home was much the same as ever, father was at GGA, mother was at home with Leslie and Dorothy was doing nursing training at Manchester Eye Hospital. I’ve just been talking to Dorothy today as I write this, asking whether she can remember Bernie Simms taking her out one night, he was on embarkation leave as well, she can’t remember a thing about it. As I remember it Bernie spun her some yarn about her meeting him at the end of Heaton Moor Road where he would pick her up in his car. I think he turned up on the bus with some cock and bull story about it having broken down. Whatever, Dorothy was very scathing about the sort of blokes I was mixing with in the army!

Pat Crawford with Old Alex and a grand daughter at Dubbo in 1950. Alex would be about 95 here. He was my granddad.

One bit of excitement while I was at home was a visit from my cousin Pat Crawford who was over in this country playing for Australia in the Ashes tour. This was so important that father let me have the car to drive Pat around. We got on well together and he went on to play in the 1955/56 Test Series. Afterwards, he signed as professional for the East Lancashire Cricket club during the Aussie winter months and met a lass from Blackburn called Sheila Wharmby who he married, I have an idea he did a second year at Church Cricket Club as pro. They had a boy but sadly, shortly afterwards Pat went AWOL back to Oz. The last anybody heard from him was in the late 50’s when he was managing a pub somewhere in the Outback, Uncle Stan did all he could to find him but as far as I know his wife never heard from him again. This was a big disappointment for father, he thought, and I agreed, that this was a lousy way to treat anyone. [In 2009 I got word that Pat had died aged 75, he was almost three years older than me and left a widow, he must have re-married.]

Re: National Service

Posted: 26 Feb 2019, 04:08

by Stanley

Leave was soon over and it was back to Colchester where we got stuck into packing everything up ready for the move to Berlin. I was about to leave England’s shores for the first time! This was in Spring 1955.

I had a strange experience at Colchester before we left. We had got into the habit of going for a drink at a pub in the main street which had a gentlemen only bar. This was presided over by a well built lady who ran a tight ship. We liked it for that reason, there was never any trouble with drunken and licentious soldiery in there. I have an idea the pub was called The Crown. One night though we got a bit silly and started drinking shorts, we must have been bored because we worked our way along the shelf behind the bar. The barmaid told us that it would end in tears but we took no notice, a couple of hours later we reached the Tia Maria and I decided it was a good time to go out the back and have a pee. That was the last thing I remembered for a while until I came to in the arms of the barmaid in the back of a large car driving sedately along the road to the Barracks. She told me that they had taken pity on me and were taking me home to bed. I remember clearly telling her she reminded me of my mother and just before settling down again on her ample bosom commented that if they drove in through the gates they would probably get the guard turned out for them! Imagine my horror when that was what happened, out sprang the guard resplendent in shiny boots and crisp uniforms and as they crashed to attention the driver of the car got out and walked slowly round the back. I was wishing a hole would open and swallow me up but had to admit that the bloke was doing all right. He inspected the guard, congratulated the Provost Sergeant on the turnout (by the way, it was he of the turds in the wash basins) got back into the car and drove down the lines. He knew exactly where to go and they helped me into the hut, laid me face down on the bed (the barmaid whispered in my ear that this would stop the dreaded whirling pit), he said goodnight, she kissed me goodnight and off I went to sleep.

Shortly after I had a rude awakening when I found the Provost Sergeant shaking me and frothing at the mouth. He didn’t like me because he knew I had sussed out his washbasin fetish. I didn’t understand what was going on but remember Ted Lancaster coming out of his little cubby hole at the end of the hut and asking what I had done wrong. As I was innocent of any breach of Queen’s Regulations I was left to sleep it off. The following morning Ted took me on one side and asked me where I had been the night before. I told him and asked him what was going on, he told me that the bloke who had brought me back to the billets was the Brigadier commanding the Colchester area and that was why the guard had turned out for him. I got a message later in the day from Major Cross, our Officer Commanding the company saying that from then on I was limited to one free Guinness every night in the gentlemen’s bar until we left on posting but that if I was seen drinking anywhere else I would be in the glasshouse so fast my feet wouldn’t touch the ground. To this day I don’t know who the bloke was but he certainly did me a good turn and I have never forgotten it.

BERLIN 1955 AND 1956

The first trip abroad must always be a memorable event but I think it was even more so for me because of the circumstances. We weren’t going on holiday but as a fighting unit dedicated to helping the defence of Berlin. This might seem a little melodramatic today but in those days Berlin was a beleaguered city, surrounded by the Russian Zone and divided into four occupied sectors, Russian, American, French and British. In 1948/49 the Russians had blockaded the city and it was supplied by air lift by the Allies. By 1961, the Berlin Wall was built to seal off the Russian Sector from the West. When I was there we had access to the Russian Sector quite freely but it was an uneasy truce as the Russians saw Berlin as an obstacle to their long term aim of making East Germany an autonomous state under communist control. I can remember this being a bit of a puzzle because we knew that in the war Russia had been an ally and we could all remember the heroic battles they had fought and the lives lost on the terrible convoys to Murmansk to get supplies to them. Now we were told that they were the enemy, very strange…

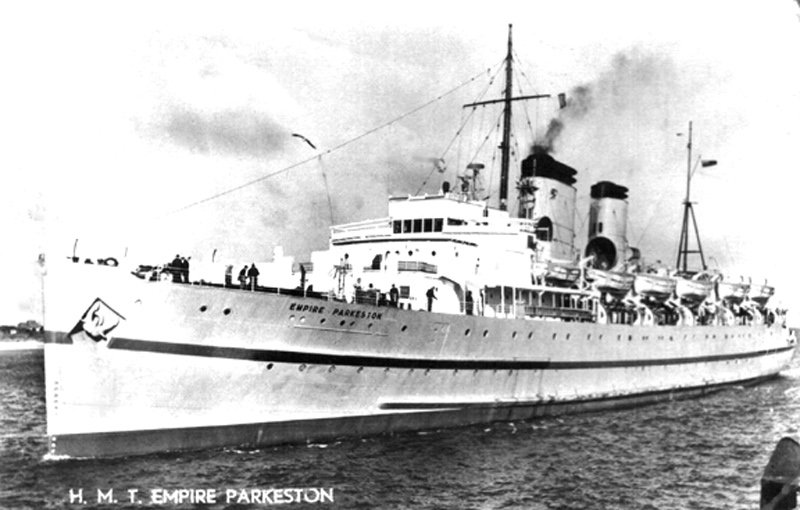

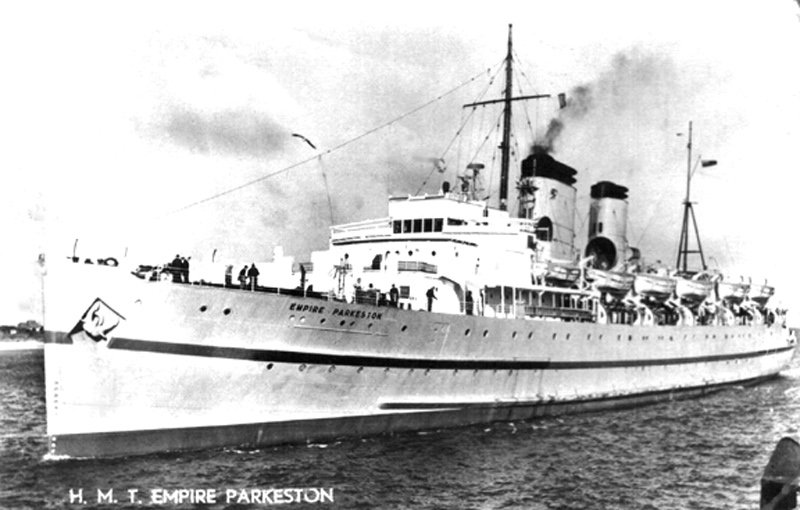

The battalion embarked at Harwich on the Empire Parkeston, the troopship which was to take us to the Hook of Holland. We were crammed into the ship and fed on mulligatawny soup, bread and tea. I asked one of the crew whether the rough finish on the paintwork below decks was some sort of fireproof coating and he told me that this was the barnacles from when she was last sunk! The crew told us the ship had started off in life as a German cattle boat, we had sunk it and raised it at the end of the war for conversion into a troopship. I seem to remember that eventually it sank again at its moorings in Harwich. However, this night it didn’t sink. I later found that as usual, the navy had been telling porkies. The Parkeston was the largest of the three troopships on the Harwich-Hook run weighing in at 6,893 tons. Built in 1930 and originally named the “Prince Henry”, it was purchased from the Canadian Government and renamed “Empire Parkeston”, Possibly because the quay that the troopships sailed from was called Parkeston Quay, just along the River Stour from Harwich. It was scrapped in 1962. It’s possible that the canard arose from the fact that one of the three ships was an ex-German minelayer.

Her Majesty’s Troopship Empire Parkeston.

We set off and soon realised that the North Sea was in a bad mood. Before long the heads were awash in half digested mulligatawny soup, I have an idea that they had a good reason for feeding us on soup, it made it easier to clean up by hosing down if there was a rough crossing. I was a bit queasy but survived without being sick and about seven hours later we disembarked and got onto the Blue Train which was to take us to Berlin.

The train ride was great, I’ve always loved train travel and this was a real journey, it took us over 24 hours to reach Berlin. Everything we saw was new and I soon became an important bloke because of the smattering of German I had picked up at school. I remember one of the lads commented on the fact that the Germans didn’t seem to have much imagination because all the stations were called Ausgang! I also remember clearly seeing the overhead railway running over the river at Wuppertal. Eventually, after several changes of loco we reached the border between West and East Germany. I’d like to say that it was here we saw our first Russians but we were made to lower the blinds before we got to the border and they weren’t raised again until we entered the British Sector in Berlin, very boring. The Russians didn’t want us to see anything as we passed through. This raised the question what they had to hide.