Another change brought about partly by the war but also by the general inter-war decline in the industry was that the tramp weavers disappeared. There used to be a pool of itinerant weavers, most of them excellent workers but averse to working in the same place all the time, they liked to keep moving. This was why we had the model lodging houses down the Butts, they had to sleep somewhere. Between the wars every mill in Barlick had a group of tramp weavers waiting in the warehouse at setting-on time in the morning. Any weaver who wasn’t at the looms ready for the engine starting was replaced by a tramp weaver and lost a days pay. After the war the shortage of weavers ensured that time-keeping became more relaxed.

In the five years after the war much had changed and the industry looked almost healthy despite what the manufacturers saw as retrograde steps. This was an illusion, things were slowly declining overall but in the better connected firms with reasonable orders this wasn’t immediately evident. Curiously enough one of the major factors that damaged the industry was the efficiency of the contract system overseen by the Royal Exchange in Manchester. Profit margins had always been low because of the security of this system when orders were plentiful. Once orders started to drop there was no room to improve the margins and another factor kicked in that wasn’t fully appreciated at the time. We need to look at the economics of the weaving shed and the effects of running under capacity… I can hear you groaning, deep joy, we are going to delve into economics. Bear with me, it will make the rest of the story easier to understand.

TEA BREAK: CONDITIONS IN THE MILL

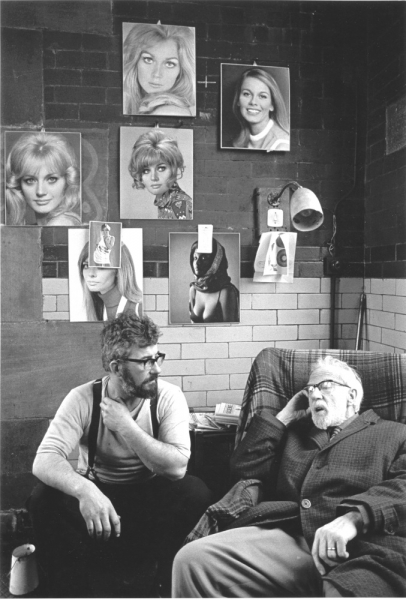

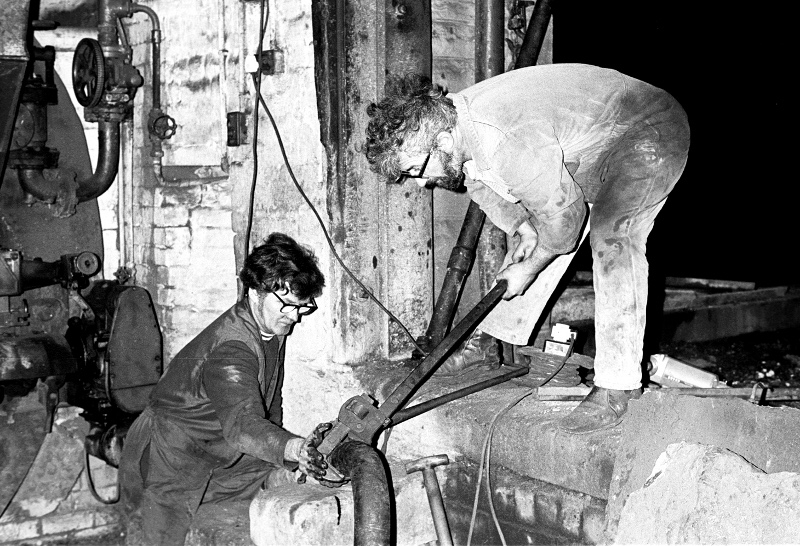

Fred was a mine of information on the inner workings of the mill and if I were to start to tell you all about that we would be here for a long time. He explained the role of tramp weavers and the practice of standing for work in the warehouse waiting to take the place of any weaver who didn’t turn up on time. He described the pressures put on the weavers by making them account for all their waste in the warehouse. I questioned him particularly about the pressure the tacklers could put on the weavers in their set if they were not performing well enough, remember that the tackler’s wage in those days depended on how well their weavers wove. All this evidence helps to build up a picture of how the management indirectly enforced discipline on the weavers to the point where it could be described as repression. Round about the 1930s this ethos started to change as the workers became more militant but traces of it hung on until the Second World War.

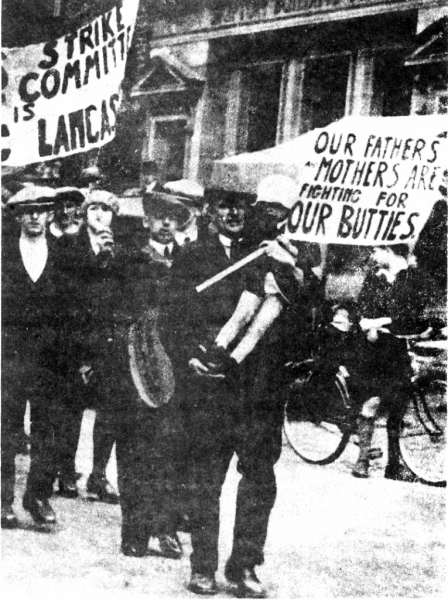

Fred also gave me evidence that supported my belief that a ‘black list’ was operated in the trade. This is incredibly hard to prove definitively but too many people have averred that it happened for any historian to ignore it. Talking about the strikes and picketing against the perceived evils of the ‘More Looms’ system he said “But that were a funny thing weren’t it. You went out on strike, you didn't know who were going to finish. You knew so many were going to have to finish, they didn't know who, and probably some of them what come out on strike and happen stood about a bit picketing, well them were marked, they didn't get back at all.” I asked Fred directly whether a black list was operated and he was absolutely definite that it did. In other words, the manufacturers were using the excuse of militancy to weed out workers to ease the necessity for running more looms. This was always covert, I will never be able to prove it as a fact but I think the evidence points us towards this conclusion.

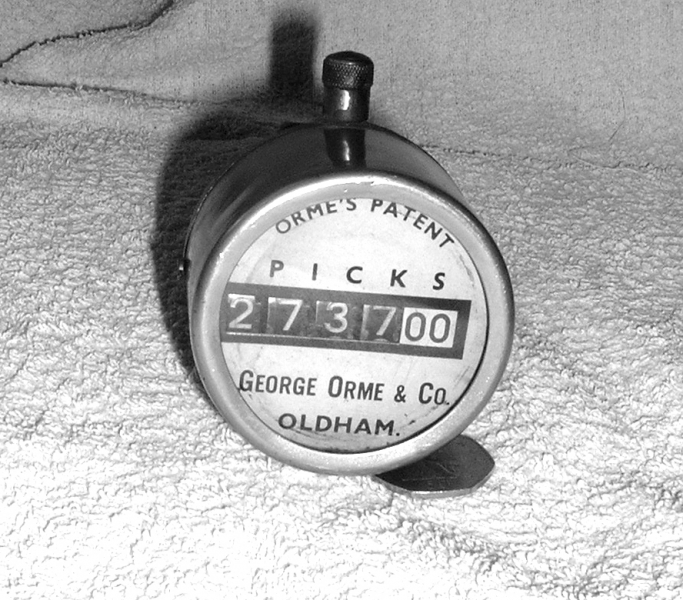

We talked about the practice of ‘time-cribbing’, starting the engine early and stopping late to get a few more minutes work out of the weavers. Fred told me about the informal network that the manufacturers ran to make sure the factory inspector didn’t catch them contravening the regulations. “And so they'd gain all them minutes, which add up over a period. I can well remember this. They’d come round would the tacklers and they'd say ‘Inspector’s coming round’. No young person or woman had to be in that mill and as soon as the engine stopped they'd to get out and they hadn't even to come in until the engine started, and that minute and half while the engine were getting its speed up they'd to oil their spindles and then they'd to be ready. They hadn't to oil their spindles while the engine were running according to the inspector. Well that inspector had probably been at Colne, they’d ring that through from Colne to Earby or Barnoldswick and they'd have somebody on Earby station. Station master ‘ud probably know this inspector and if he got on the train to Barlick he’d ring 'em up at Barlick and he’d also ring ‘em up at Earby. “He’s gone to Barlick!” He hadn't much chance of catching anybody hadn't the inspector 'cause it were all worked out, everybody know before he landed.”

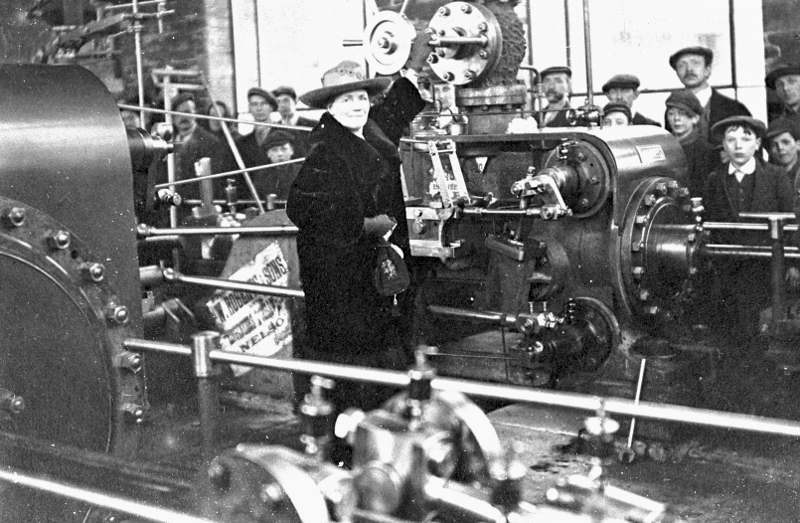

I know this sounds like something out of an Ealing comedy but given the close-knit relationships inside the trade and the local community I am absolutely sure that Fred is correct. Not only that, but as late as 1977 when I was running Bancroft engine there was a relationship between management and the inspectors and we always had prior warning of an inspection. I am not suggesting that this relationship was corrupt, indeed, I doubt if it could be. The process was that the inspectors knew that they had the power to cause the manufacturers a lot of trouble if they wanted to but in the end this would do the local economy no good at all in a period of bad trade. Shutting a mill down temporarily because of a minor infraction of the regulations wouldn’t help either the managers or the workers and in the end, the rules were there to protect the employees. This relationship didn’t always hold good, particularly in the early industry when there was a national campaign to improve the lot of the workers, particularly children, in industry. In Leonard Horner’s report to Parliament as Chief Factory Inspector for the half year ending in April 1850 he said that when he visited Mr Bracewell’s works [Old Shed, Earby] he was tipped off that under-age workers were hiding in the privies. He took a policeman and found ‘thirteen young children, male and female, packed so close together as they could lie on each other’. Colne magistrates fined Christopher Bracewell £136, this would be about £4,500 in today’s money.

Fred told me two more tales that illustrate the attitudes in those days. “Saturday morning, the engine stopped, we'll say at half past ten and you were dashing out, you’d get a black look, you were supposed to stop behind and clean your boxes a bit and titivate things up. And tacklers round here, they'd be same in Barlick and Earby, they never had to go home while twelve o'clock, unless there were sommat extraordinary. They’d to stop in and go round fastening spindles and putting buffers on, doing odd jobs, any warps out, gait warps. There were one instance a fella what comes in the White Lion now [1978], he’d be about seventy four, and he told a tale about there were a medal competition one night when football were on and there were three on ‘em weaving. As soon as the engine started slackening they stopped all their looms and run out. When they got to the door there were one of the bosses there. Now lads he says you’re coming out faster than what you go in, he says get back to your looms and come out at the same speed as what you go in. This chap said we daren’t do anything but walk back in and then walk out quietly. And then another time I'd been to the toilet and I were just fastening me pants up and he came did this boss. He says “Hasta been smoking?” “No, I don’t smoke.” (Sniffing sound) So he says, “It's twist smoke is that, somebody's been smoking twist.” I thought it's a damn good job I hadn't been smoking or he might have sent me home for the day or sommat like that.”

Life is always a balance between the good and the bad. It’s no use viewing the past through rose-tinted glasses, we have to report honestly, these things happened within living memory. In some ways at least, we have improved attitudes towards the workers but I often think that traces of the old ways still persist. I’ll leave it up to you to make up your own minds.

The Model lodging house in Butts in about 1920.