CHAPTER 27: SALTERFORTH SHED

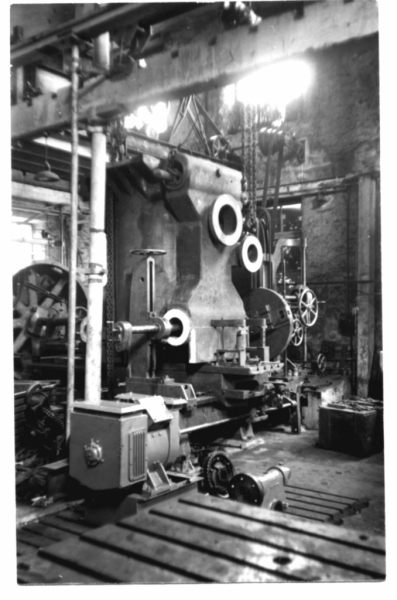

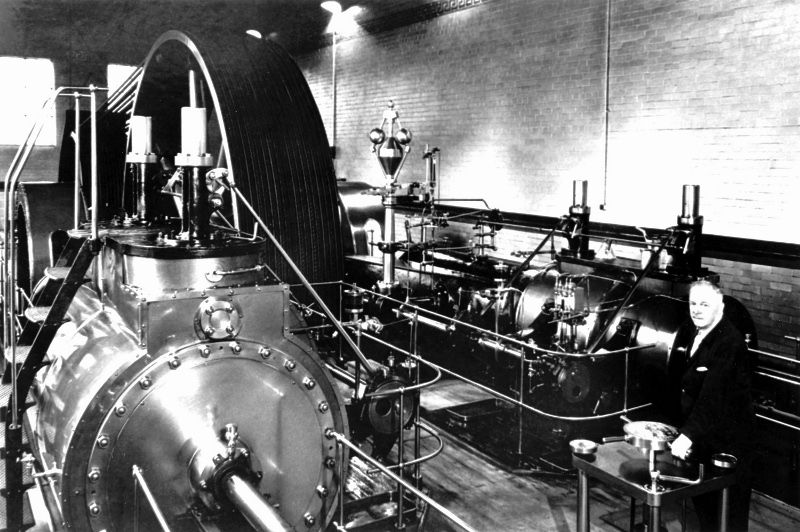

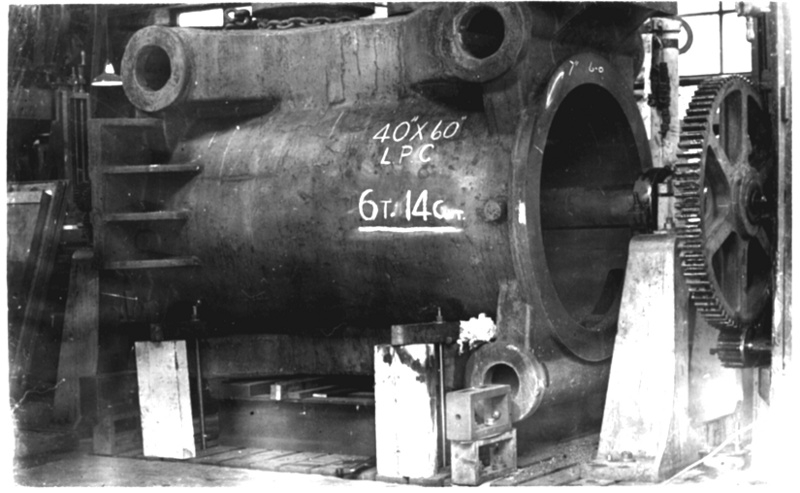

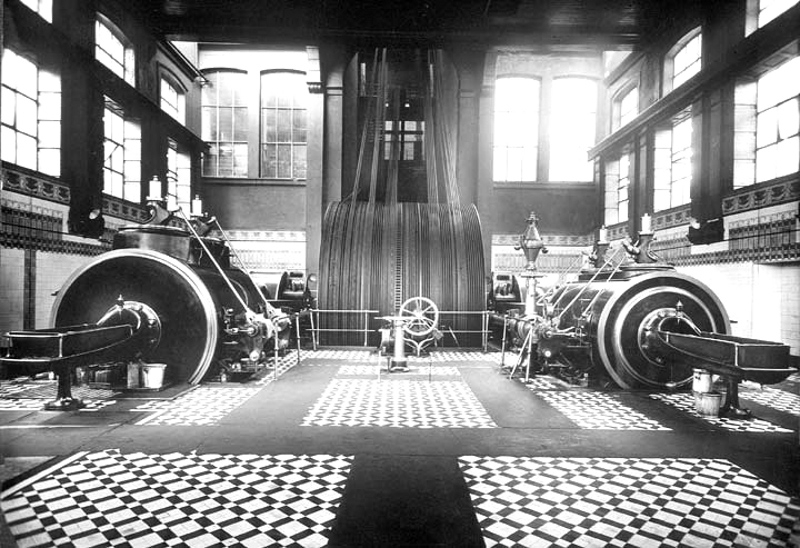

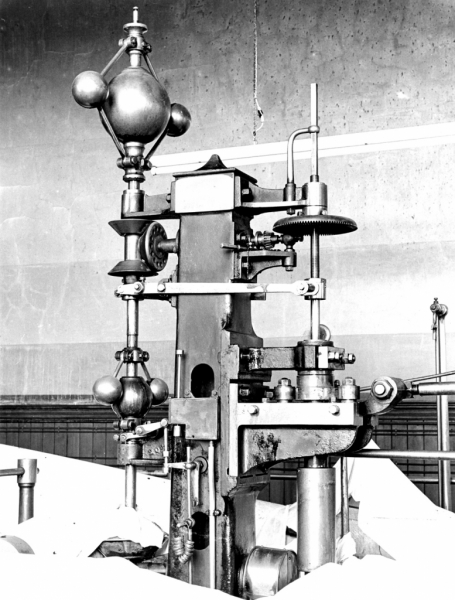

I asked Newton about Salterforth Shed (1888) because I knew he’s done a lot of work down there. “Oh, Salterforth, lovely. James Slaters at Salterforth, a little Roberts tandem, cost £395 to make and put in. Slide valve low pressure, slide valve high, Meyer (type) cut-off gear, which’ll take a lot of explaining will that, I don’t know where to start. It’s a Porter governor working some cams advanced and retarded which altered levers on the slide valve steam chest. These levers were connected to a double slide valve with some ports in and this gear altered the opening of the ports and so altered the cut-off and governed the engine. (A normal slide valve can’t be adjusted for cut-off, this is dictated by the way the valve is made and so the engine can only be governed on the throttle by an equilibrium valve. The Meyer gear was an attempt to change this and they were very effective but soon replaced by Corliss valves and later drop valves. The only engine I know that has this gear is the Yates that I moved from Jubilee at Padiham to Masson Mill at Matlock Bath in Derbyshire. I later discovered that there was more than one version of slide valve expansion gear and the one that Newton is talking about was probably Roberts’ version but the same principle.) A very efficient gear.

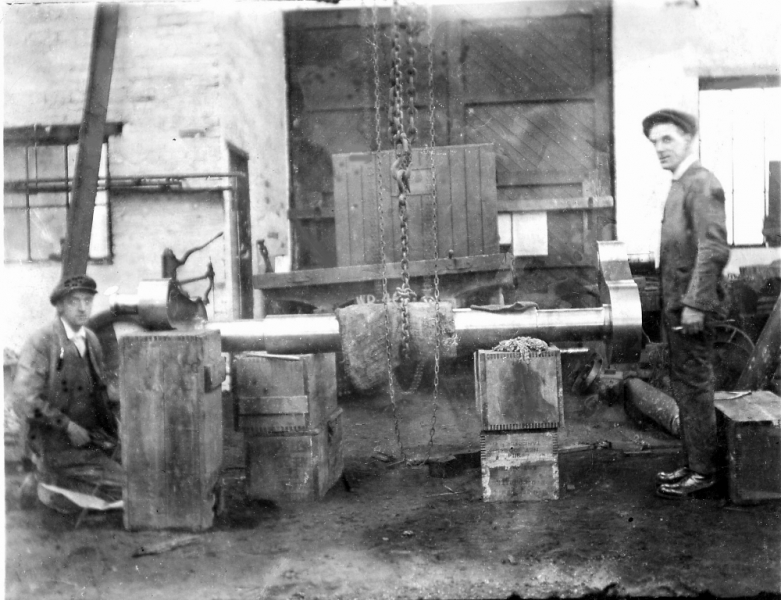

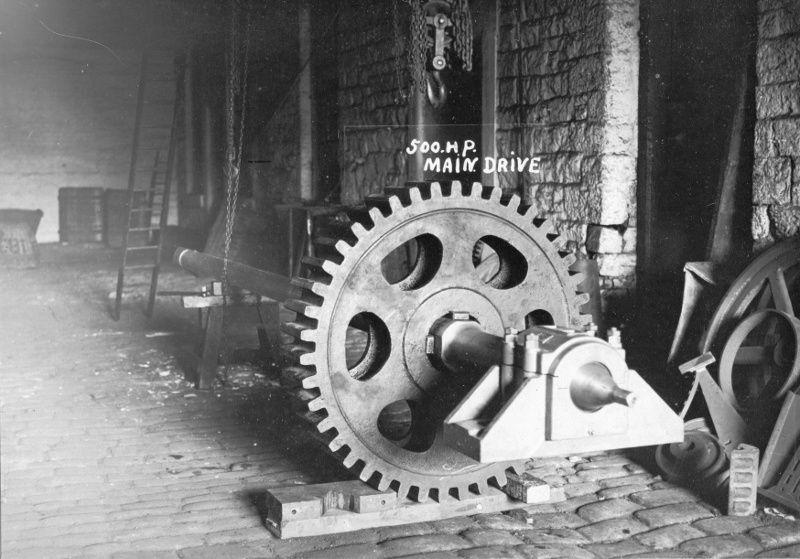

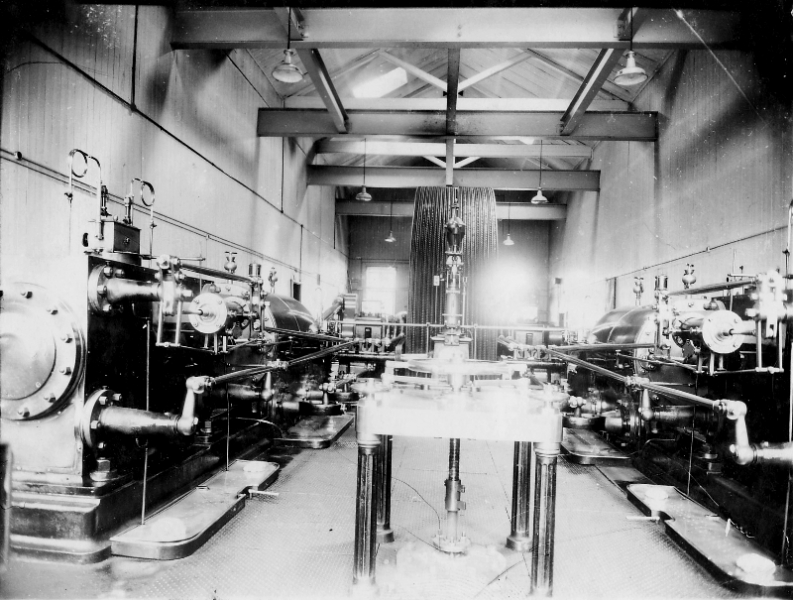

It run at about 40 or 45 revs a minute, it’ud be four foot six stroke, beautiful flywheel and gear drive. The gears just ran like wood wheels, you could hardly hear ‘em, just rumbled, it were a beautiful thing. I had a few weeks there at one time, they had a fire you know. (Craven Herald 29th of March 1929 reports a fire at Salterforth Mill on Friday 22nd of March. The fire was confined to the engine house roof.) It brought the engine house roof in and it weren’t long afore they had it running. It bent the governor shaft and I went down, I were only a lad then (13 years), I went down wi’ the men and we soon had it straightened up. They got a good joiner there, Tom Parker, and he soon had baulks across and a new roof on. Oh, it’d happen be running in a fortnight or so.

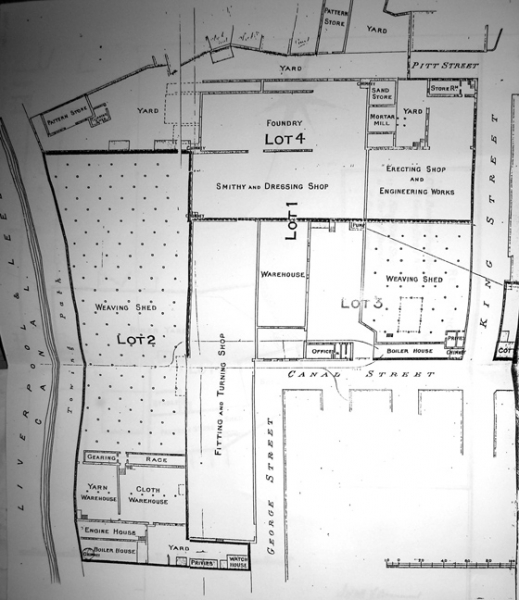

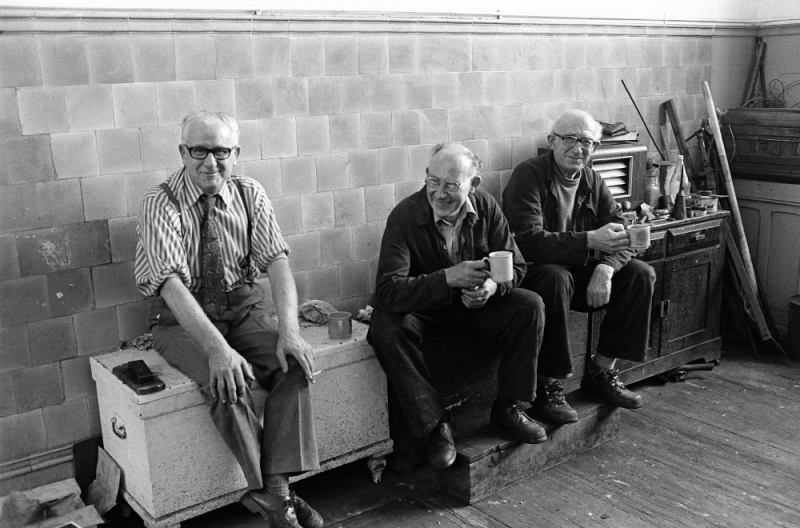

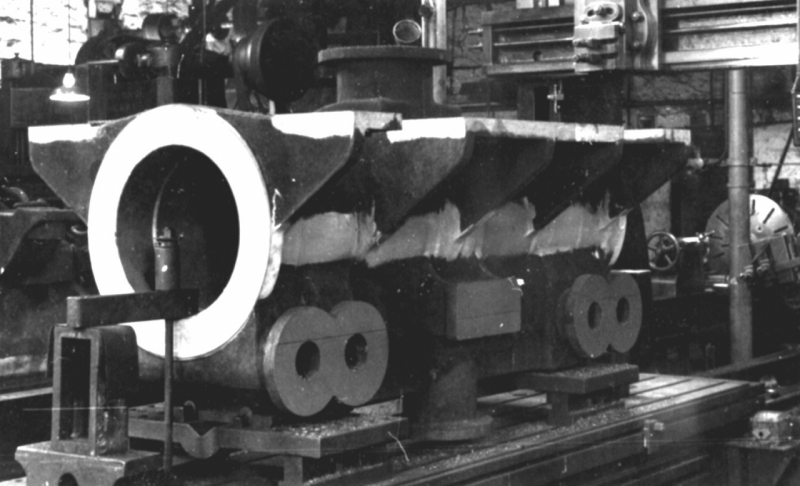

Then during t’war it was stopped and after t’war me father said to me one day, Jim Slater’s rung up from Salterforth Newton and he wants you to go down there and get the engine running, will you go down? I says course I will! So I went down and Donald Plummer had got t’job of engine driver, he were with his father running Coates Mill and little Donald, he’s at Wellhouse now (1978), he got th’engine at Salterforth after the war. So off we went to Salterforth and Donald’s already there. He’d got it cleaned up and it looked alright but they just wanted me to give it the once over before they ran it and it were funny, I looked at the flywheel, it weren’t cased in then because that‘s where the fire had started and I said to Harry, it does look funny does that flywheel, I’m going to get me father down here. I came up to t’shop and I says the segments on Salterforth flywheel look a bit funny to me, they’re a little bit out. He says how much? Well, I says, you can feel it with your finger. Oh he says, don’t bother me wi’ it, they’ve given us a free hand, lift one off. Just like that, lift one off! They weighed about two ton apiece, they’d be about ten inches wide and about eighteen inches deep, they were the rim of the wheel. Just exactly, more or less, like that wheel at Harle Syke so you know what I’m talking about. They were cottered you know. So we got some girders across and some tackle up ‘cause they’d put the new roof up without girders, it were just oak baulks. So we put some girders up across two of the baulks and we got some blocks on and gets the cotters knocked out and we lifted this segment off and my god, it were a good job we did!

These segments have a square hole cast in where they fit on top of the arms and then you’ve a cotter hole through your segments and a cotter hole through the top of your arms and you’ve gibs and cotters in there. Well in there you’ve a two and a half inch square dowel that your cotters fastened to at each end and that’s what ties your segments on to the top of your arms. They were both broken were them dowels. So we lifted that quietly on to the floor and Harry says hadn’t we better take another off? So out of six segments that made the gear up, it were a six arm wheel, there were five of them dowels broken. Them segments were just hanging on the top of them arms wi’t sheer fit of being cottered that way. It were just a ring loose on top of six arms more or less, except for one dowel. Every one of them broken right slap in the middle, that ‘ud be done in the fire you know. When the wheel expanded with the heat of the fire it’d stretched them dowels but when it went cold, when t’arms pulled back again to their original length it’s broke ‘em off, every one. And that engine had run like that, it must have run ten years after t’fire like that. Anyway, we put all new dowels in it of course and put the segments back on, all the gearing back on and we were there many a week with that job. We got it running and it ran until the end of its days with no trouble.

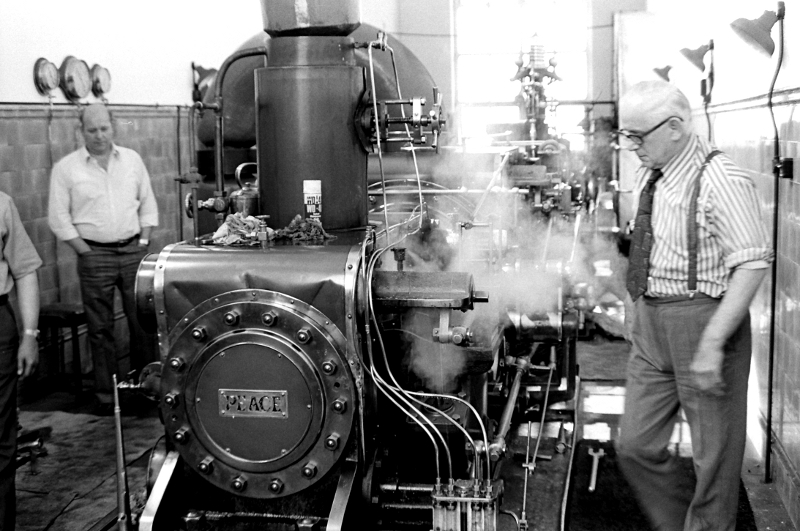

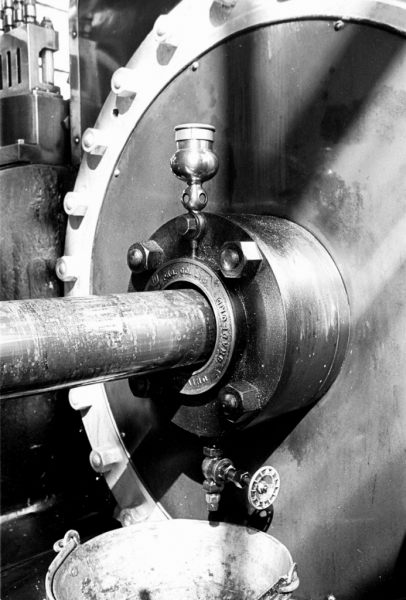

We just had one little do with it, we put a new equilibrium valve on it. It were an equilibrium valve knock-off and the insurance were getting particular about stop motions. We tested it and found that when we knocked it off it wouldn’t stop so we took the equilibrium valve out and it were very badly worn. Me father and Denis took particulars for a new one and they made a new valve for it. (What Newton is talking about here is the automatic stop motion on the engine. This is a mechanism which is triggered either by a violent fluctuation in engine speed, up or down, or by breaking the glass on a box in the mill very similar to a fire alarm. The way the signal actually stops the engine is that it triggers a mechanism that shuts the steam off. On a Corliss valve engine this is easily achieved by breaking the linkage to the valves which then stay shut. On other engines it was effected by a spring loaded stop valve which shut itself when the catch holding the spring was released by the signal. On the Salterforth engine an older system was used, the signal actuated a special type of valve which could be closed by a simple weight. This was achieved by making the valve very easy to close. The problem with normal valves is that when they close they have to act against the boiler pressure on the valve. The equilibrium valve was made with two seats arranged so that boiler pressure acted against the outside surfaces of both valves with steam passing to the engine through a central passage between the valves. This meant that the weight of steam on the two outside surfaces opposed each other and achieved equilibrium at any port opening, hence the name given to the valve. The problem with equilibrium valves is that as the two valve faces are a fixed distance apart, it is crucial that both faces coincide with each other exactly when the valve closes. This is the problem Newton is about to come across.)

Dennis and I went down at Saturday morning a week or two after to replace the valve. We put this valve in and we’d made a special cutter to re-cut both seats, you know, right good, grind them in and both seats touching perfect. Puts it all together, sets it on and knocked the stop motion off, I just tapped the hook (In the linkage) and knocked it off. No, it didn’t stop! Well, Johnny said we’ll have to put a vacuum breaker on it. I said I told you that didn’t I, it wants a vacuum breaker on! (Even when the steam is shut off the vacuum in the system can keep the engine going. The cure is to have a valve in the system between the low pressure cylinder and the condenser which opens to atmosphere and destroys the vacuum.) Oh, me father says, it’s nowt isn’t that, we put a vacuum breaker on you know, piped it up during the week ready for coupling up, coupled it up on Saturday. Right, start her up Donald, reight big stop valve hand wheel, you’d have thought you were starting Mons engine, it were about two feet in diameter. Started it up, knocked it off, it didn’t stop did it. Me father tells me it’s an odd do is this, you’d better go down and grind that valve in again, re-face them. So I goes down meself with Bob Fort this time we re-faced it again with the special cutter, just took a thou off, ground the valve in and I turned round and I says to Bob, it never bloody well will stop! Oh, he says, don’t tell thi father, don’t tell thi father what tha says or there’ll be a reight row! I says It never bloody will stop, go on Donald, try it again. He sets on does Donald, knocks it off, it slowed down but the bugger wouldn’t stop, it just trailed on without vacuum until the air pump sweltered (boiled). So I went back to t’shop Monday morning, well, how’ve you gone on wi’ it this week? That’s how he talked you know. Were it all right? No, I said, it’ll never stop, it’ll never stop in a bloody month of Sundays Johnny won’t yon thing! He says, why, is it cracked in’t seats or sommat? I says No! He says well what’s up wi’ it? I says well, it’s a cast iron box and tha’s made a brass valve. Oh bloody hell fire! he says, just like that. Get that pattern to’t foundry, up to’t Ouzledale and tell ‘em to make a cast iron one. He he he. It were the heat expanding it, the brass were lengthening a sixteenth more than the bloody box. He he he! He thought they were doing something clever when they put a brass one in. Gun metal, lovely thing it were, all fluted with ribs on. I just says to Bob that morning we’re wasting us bloody time, we might as well have been out courting or sommat, it never will bloody stop. It must have been a sixteenth longer than t’box when it got hot and it ‘ud be whistling through the top seat as happy as a lark would t’steam wouldn’t it. Engine kept trailing round and round at about five revs a minute, just the same every weekend, trailing round at about five revs when we knocked off. It never stopped, it were getting enough steam to keep it going.

Aye, that were Salterforth. We electrified Salterforth oh, 1955 or 1956 (Geoff says 1949 and I think he is right.). It were one of the first sheds to get electrified. The boiler were done tha knows. Me and me father went to Yates and Thom at Blackburn, it were a special size boiler and you couldn’t put anything bigger in the boiler house. I think it were only a seven footer wi’ two fire holes. I think it were a seven footer or seven foot six, it weren’t an eight footer anyway, because an eight footer wouldn’t go in there, there wasn’t room for the side flues and the side flues were narrow enough, they used to have a job to flue ‘em. Me and me father went to Yates and Thom and they promised to make us a new boiler. Anyway, the insurance company did a rotten trick wi’ ‘em at Salterforth, they pulled their insured pressure down from 120 to 100psi. Now you could only just manage wi’ 100 pound when you’d all the looms running. They said you’re all right now, you can stay at that for ten years. They walked in the summer after and said it’ll have to come down to 80 pound and that did it. They more or less condemned it and they’d just had new connies put in and all. So me and me father went to Yates and Thom, the insurance company give ‘em a bit of grace to see whether they could make a new boiler for it and they said they could. They said they would make them a new ‘un. Anyway they weighed one thing against another, they talked about package boilers and me father said it wouldn’t do, he said it’d just prime it away. So they decided to electrify the shafting. We put motors up on the wall, electrified the shafting and after that they sailed on. It ran a lot of years and they kept the boiler in. Oh, that were another thing they told ‘em, they said righto, if you do away with the engine and electrify the shafting we’ll let you keep your boiler and work it at 60pound for the heating. One winter, and that were it, it ran one winter and they condemned the boiler altogether. They’d to go out and buy a new boiler. I don’t know what their reason was, age, that were all that were wrong with it. I don’t think they could find anything wrong with it, they never said get some rivets in it or weld round the fire tubes or get new front lengths in the fire tubes. They just condemned it at t’finish up. There were a bit of a do going round then though, there were a lot of boilers condemned just round about that time that were built in the 19th century. That engine ‘ud be put in about 1885 or sommat like that? You see what’s happening Stanley with such as Pendle Street and all them shops with engines in of that age, they had their engines modified and new boilers put in in the twenties. Well they were all right, they sailed on. But such as Salterforth that had never had any trouble with their engines never did any modernising. They should have modernised it after the First World War and put boiler pressure up to 160psi with two new cylinders which would have saved ‘em coal, it ‘ud have saved the price of the job but they never had it done. See, the old people thought it ran beautiful, you couldn’t hear that engine from outside the engine house. I had an experience there one afternoon. I run it a time or two when they the engineer was poorly sick. I used to like to go to Salterforth and I fell asleep outside on the form, middle of summer and you were on your own you know. You’d both the engine and the boiler. Nobody used to come round to see you. I woke up and shook me head, I looked in through the door and I had 40pounds on the clock! I soon woke up Stan! Straight up to th’engine, it were going, just. Downstairs to get some greasy waste in the firebox and get the fire going and do you know I got steam back up, big shifts and little shifts and nobody came anywhere near! I don’t know what speed the engine were running at, about 30 revs happen. It were still going, t’governor were laid on the bottom, equilibrium valve absolutely wide open, driving on the low pressure and it kept going and there weren’t a soul came near. I looked at that clock Stan and I had 40 pound on and how many looms would I have running, 600? He he he. I were literally running on the low pressure cylinder.”

I like the story Newton tells of him getting one over his dad with the equilibrium valve but I think I can add something from my own experience when I was re-building the Whitelees engine. The use of an equilibrium valve controlled by the stop motion was very old-fashioned and was a hangover from the days when such a valve was controlled by the governor to regulate the speed on an engine. The Yates Jubilee engine which I moved to Masson Mill had exactly the arrangement Newton describes, variable ports on the high pressure slide valve and an equilibrium valve controlled by the stop motion but I have never seen the interior of it. The valve on the Whitelees beam engine certainly did have a gunmetal bobbin because I had to make a new one for it. I think the difference may have been that the valve I made was for 40psi and therefore much cooler and it may have had a shorter distance between the seats. As it was a governor valve it wasn’t critical for it to be steam tight when fully closed and it may well have been that the similar valves that Johnny had seen before were like this and so his mistake was quite natural. Like all of us, Newton enjoyed being right and it’s his story.

I do have one instance of a Newton mistake. He once told me off tape about doing a job on a big low pressure slide valve and when they were packing the tackle up afterwards they realised that they were short of a stink lamp. It wasn’t a cast iron one, it was made out of tin so they decided that it must have been left in the steam chest but would not be solid enough to cause any problems. They started the engine and ran it and it was OK. Nothing more was heard about it and Newton said it had either stayed in the chest or the steam had blown it somewhere where it could do no damage. One thing is certain, humans make mistakes and I suppose that when we listen to Newton we should bear this in mind but also remember that he’s telling his story and if he wants to put himself in the bast light it’s entirely understandable. It doesn’t diminish the quality of the information he is giving us.

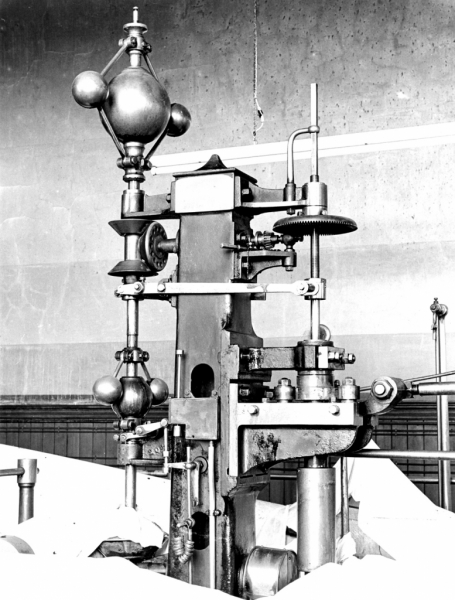

The Yates governor on the Jubilee engine which controls both the speed and the slide valve setting. If you study it long enough and hard enough you’ll be able to work out how it functions…