STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 90298

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

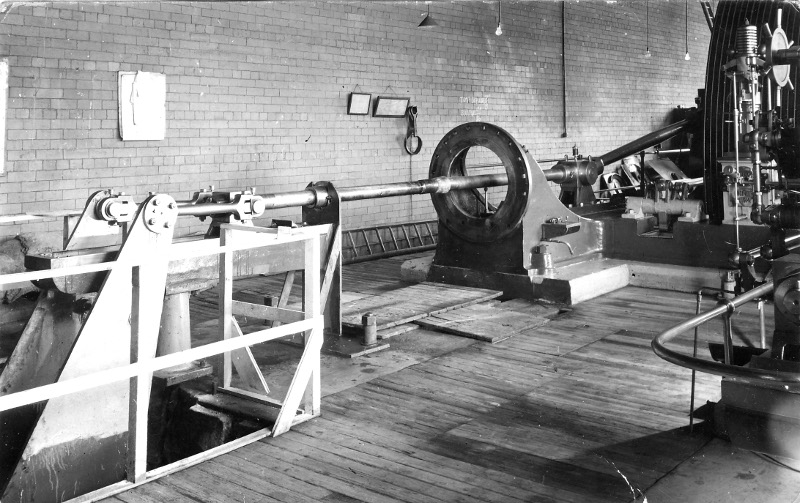

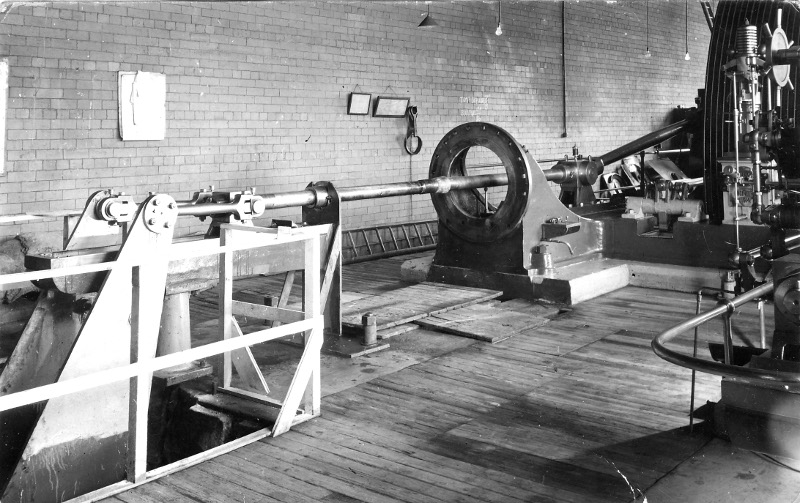

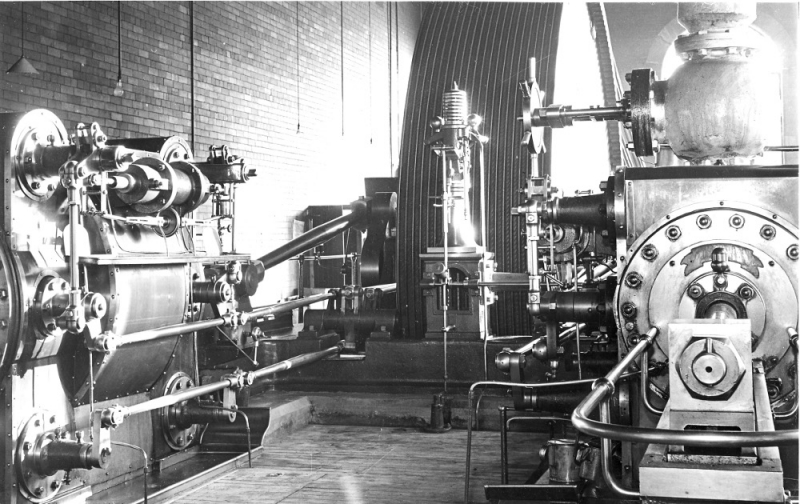

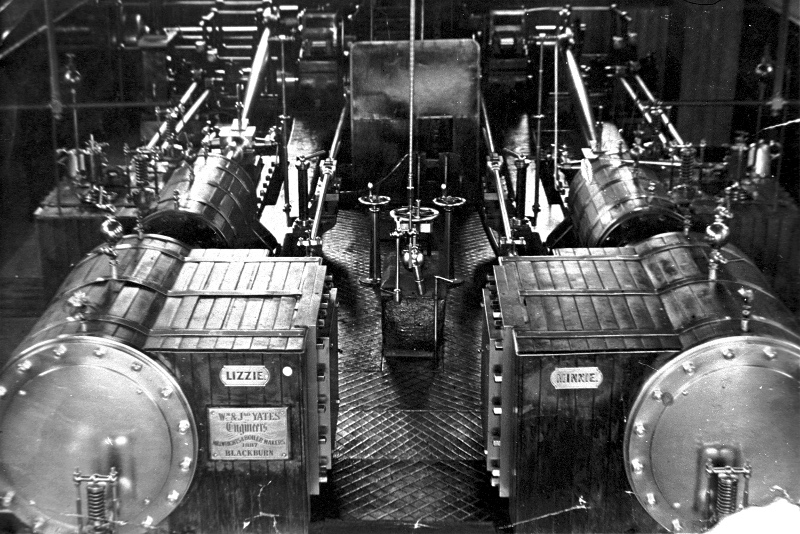

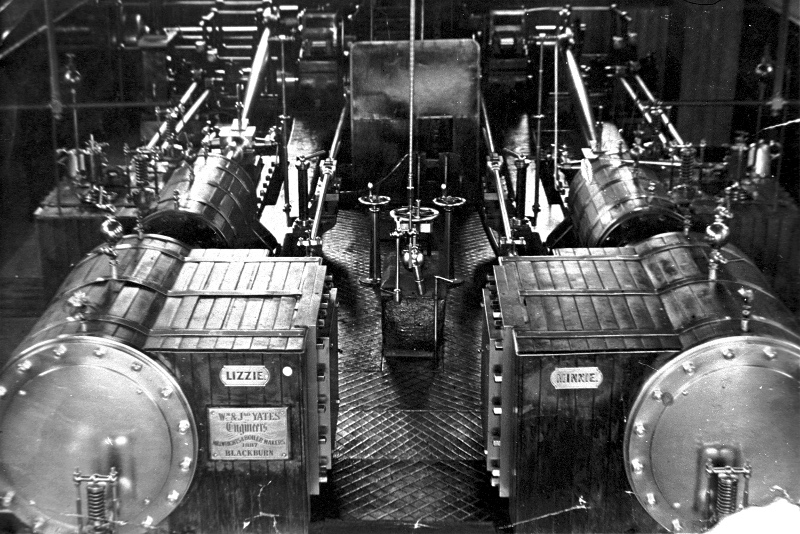

Now there were always trouble wi’ bad vacuum. Th’air pumps were absolutely jiggered. (The air pump on a condensing engine is the pump driven by the engine which removes the condensed water which is produced constantly in the condenser as the engine runs. The efficiency of this pump governs the vacuum in the exhaust system which is most important for efficiency. It pumps water but is always called the ‘air’ pump because the water has air entrained with it from small leaks on the vacuum side of the engine.) There were water squirting out everywhere bar where it should have done. The coffin bottoms had been broken and they were all cemented up and they were leaking. The delivery plates were rotten. So at t’finish up I says to me father there’s going to have to be something done about these air pumps. There’s going to have to be some new uns. He says reight oh and rings Teddy Woods up at Burnley, he were the secretary of the mill company (Edward Woods was a partner in the firm of Proctor and Proctor, chartered accountants in Burnley. They acted for many of the mill companies in the area. Edward Woods was secretary for the Earby Mill Co, he was very interested in the engineering side of the job and supervised all the engine repairs.) Teddy Woods and Captain Smith came along to the shop at Barlick. Captain Smith were the boss at Pillings (They were ironfounders specialising in loom manufacture at Primet Bridge Colne.) and he was also a big shareholder in the Earby Mill Company. They talked about this job between them and me father came out of the office and he says we’ve got a reight job Newton. I said what have we got? He said, to make two new air pumps for Victoria Mill. I said We aren’t putting ‘em in them blooming holes where the old uns are are we? He says No, we’re not, we’re going to make a completely new unit and we’ll put them in the old devil hole and run ‘em off the lineshaft, we’ll make ‘em independent. (Victoria Mill was a spinning mill in its early days and the name ‘Devil Hole’ is a hang over from that trade. It was a room that used to house the devils, the breaking machines that opened the cotton fibre up. They were called devils because they were notorious for catching fire if a small stone of piece of metal got into the drums. When I was doing the spinning section of the LTP at Spring Vale Mill in Haslingden I saw the devils catch fire several times, it was a common occurrence.) We made two sets of Edward’s air pumps all on one bed, properly independent, proper individual air pumps all fastened together in a pair like a set of twin pumps. (The design of the Edward’s air pump was superb because it did away with the need for valves on the air pump piston. A great advantage which made them very efficient and reliable.) We ran ’em by two seven foot rope pulleys with six ropes on. Now that were some job, I think them pumps weighed seventeen tons when they were on the bed. We put them in one September holidays, they stopped for a week for us and when we started up we had twenty seven and a half inch of vacuum and that engine had never had anything like that in it’s life. I never saw it wi’ more than twenty one or twenty two inch on it and the coal bill went down by seventeen ton a week. Aye, it did that and that’s fully loaded you know. Which it would do when you think about it Stanley, there were two low pressure cylinders seven foot stroke, vacuum at both sides of the piston on every stroke and that’s running at 38rpm.

That were the last major job that were done as far as rebuilding was concerned till all at once it developed a funny noise. (I asked Newton the date and he said 1953 but Johnny wrote a letter to the ME about the job in December 1954 in which he says that the shaft had run 82 years and the flywheel 57 years. So Johnny’s date for this job is 1954 and the first replacement shaft is 1874 with a new flywheel in 1899 assuming a start date of 1856. Tricky stuff this history, these dates always vary slightly from source to source but I think we are close enough.) This all started months before it happened. Me father lands in to t’shop, “I’ve just been down to Earby Newton and I’ve been in yon, I’ve been up at t’mill just to have a look at Almond (Tommy Almond, the engineer) I haven’t been for owt particular but yon engine has a queer noise. I wish you’d go down there”. I hadn’t been for a week or two so I said, Aye, I’ll go down. I sat and listened to it a long while and I talked to Old Almond and I never said nowt. I never said nowt, I came back to t’shop. (You may think that listening to the engine isn’t a very precise way of diagnosing a fault but in fact the engineer’s ears and his nose are two of the best diagnostic tools he has. Much can be learned from simply listening properly and the smell of hot metal gets your attention faster than anything else. As Newton often said of bearings “I’d rather hear ‘em than smell ‘em. Meaning of course that a bit of play was far better than a hot neck.) Me father says “What’s ta think of yon engine?” I said I don’t know, I think the flywheel shaft’s breaking. “Oh Newton, for God’s sake, look at t’size of it and don’t talk so blooming silly! There’s a bolt loose, I’ve heard ‘em make that sort of noise before when I were a young chap. There’s a bolt loose, go down there at weekend and take some men with you and run round all the bolts”. (Johnny was talking about the bolts that held the gear segments on the rim of the flywheel)

So we went down there at weekend, three of us, we’d all t’spanners and we went round all the bolts and I didn’t find anything. There were four bolts in each arm, and then in each segment, the arms were under the centre of the segments, there were gibs and cotters through, always laid flush, you couldn’t actually see ‘em when it was running, they were chipped flush so’s they wouldn’t catch anybody. Anyhow we tested everything and all the bolts were tight, all the cotters were tight. Now in between them segments they had some tapered plates and sometimes it used to get one of them loose and it would sound buzzz… as it were going through the teeth and we knew about that so we used to put new uns in. So I came back again and he says “Has it gone?” I says no, the shaft’s breaking. He walked away and ignored me when I said that. He went down again during the week, he weren’t satisfied and he came back and he says “Go down again this weekend and try all them plates”. I said I tried ‘em all last Saturday. He says “Well go down and try them again! Tha’s missed one! There’s either a bolt loose in that flywheel or there’s one of them plates loose!” I says there’s nowt loose. So anyhow, we all went down again and we went round everything and I were getting sick and Bob and Crabby were getting sick and Tommy Almond were getting sick because he couldn’t go to the pub. We didn’t find owt and this time I tried all the boss cotters, the cotters that held the arms in the flywheel boss, I tried them all and they were tight. Now that flywheel had a cracked boss and it had had some kidney rings shrunk on, so I tried ‘em and they were all right. So I came back to the shop on Monday morning. “Well, did you find owt?” No I says, the shaft’s breaking. Well he set into me good and proper, he says “What’s tha acting on about wi’ that bloody engine. There’s a bolt loose in that flywheel and give up saying that t’shafts breaking”. So I walked away and left him, I thought there’s going to be a right falling out do here over a blooming old steam engine if I’m not careful, that were at Monday. Tuesday morning outside Vicarage Road (where Newton lived) banging on the front door at quarter past seven, there were a taxi. Young Almond, Tommy Almond’s lad were there. “Newton, come down to t’mill reight sharp will you, yon engine’s making a reight bloody noise!” I says well, has yer father getten it stopped? He says “No, he won’t stop it.” I says all right, I’ll come in me own motor, I had me little van outside. I gets some shoes on and a jacket and off I went to Earby Mill. I just stood at t’back of the flywheel while it ran, it were totally enclosed in a tin case but you could see the rim. I stood there behind it and watched it and it were trembling like a fiddle string. I says to Tommy Almond, get this engine stopped quick! He says I’ll have to go round and tell the tenants first. He’d about six tenants in you know and he were well loaded, he had about 1300hp on. I said reight oh Tommy, thee go and tell thi tenants and as soon as he went down t’ruddy steps Newton went round to the governor and pulled the catch off and shut the stop valve. Th’engine stopped, tenants or no tenants and the flywheel shaft at the low pressure side were smoking.

That were the last major job that were done as far as rebuilding was concerned till all at once it developed a funny noise. (I asked Newton the date and he said 1953 but Johnny wrote a letter to the ME about the job in December 1954 in which he says that the shaft had run 82 years and the flywheel 57 years. So Johnny’s date for this job is 1954 and the first replacement shaft is 1874 with a new flywheel in 1899 assuming a start date of 1856. Tricky stuff this history, these dates always vary slightly from source to source but I think we are close enough.) This all started months before it happened. Me father lands in to t’shop, “I’ve just been down to Earby Newton and I’ve been in yon, I’ve been up at t’mill just to have a look at Almond (Tommy Almond, the engineer) I haven’t been for owt particular but yon engine has a queer noise. I wish you’d go down there”. I hadn’t been for a week or two so I said, Aye, I’ll go down. I sat and listened to it a long while and I talked to Old Almond and I never said nowt. I never said nowt, I came back to t’shop. (You may think that listening to the engine isn’t a very precise way of diagnosing a fault but in fact the engineer’s ears and his nose are two of the best diagnostic tools he has. Much can be learned from simply listening properly and the smell of hot metal gets your attention faster than anything else. As Newton often said of bearings “I’d rather hear ‘em than smell ‘em. Meaning of course that a bit of play was far better than a hot neck.) Me father says “What’s ta think of yon engine?” I said I don’t know, I think the flywheel shaft’s breaking. “Oh Newton, for God’s sake, look at t’size of it and don’t talk so blooming silly! There’s a bolt loose, I’ve heard ‘em make that sort of noise before when I were a young chap. There’s a bolt loose, go down there at weekend and take some men with you and run round all the bolts”. (Johnny was talking about the bolts that held the gear segments on the rim of the flywheel)

So we went down there at weekend, three of us, we’d all t’spanners and we went round all the bolts and I didn’t find anything. There were four bolts in each arm, and then in each segment, the arms were under the centre of the segments, there were gibs and cotters through, always laid flush, you couldn’t actually see ‘em when it was running, they were chipped flush so’s they wouldn’t catch anybody. Anyhow we tested everything and all the bolts were tight, all the cotters were tight. Now in between them segments they had some tapered plates and sometimes it used to get one of them loose and it would sound buzzz… as it were going through the teeth and we knew about that so we used to put new uns in. So I came back again and he says “Has it gone?” I says no, the shaft’s breaking. He walked away and ignored me when I said that. He went down again during the week, he weren’t satisfied and he came back and he says “Go down again this weekend and try all them plates”. I said I tried ‘em all last Saturday. He says “Well go down and try them again! Tha’s missed one! There’s either a bolt loose in that flywheel or there’s one of them plates loose!” I says there’s nowt loose. So anyhow, we all went down again and we went round everything and I were getting sick and Bob and Crabby were getting sick and Tommy Almond were getting sick because he couldn’t go to the pub. We didn’t find owt and this time I tried all the boss cotters, the cotters that held the arms in the flywheel boss, I tried them all and they were tight. Now that flywheel had a cracked boss and it had had some kidney rings shrunk on, so I tried ‘em and they were all right. So I came back to the shop on Monday morning. “Well, did you find owt?” No I says, the shaft’s breaking. Well he set into me good and proper, he says “What’s tha acting on about wi’ that bloody engine. There’s a bolt loose in that flywheel and give up saying that t’shafts breaking”. So I walked away and left him, I thought there’s going to be a right falling out do here over a blooming old steam engine if I’m not careful, that were at Monday. Tuesday morning outside Vicarage Road (where Newton lived) banging on the front door at quarter past seven, there were a taxi. Young Almond, Tommy Almond’s lad were there. “Newton, come down to t’mill reight sharp will you, yon engine’s making a reight bloody noise!” I says well, has yer father getten it stopped? He says “No, he won’t stop it.” I says all right, I’ll come in me own motor, I had me little van outside. I gets some shoes on and a jacket and off I went to Earby Mill. I just stood at t’back of the flywheel while it ran, it were totally enclosed in a tin case but you could see the rim. I stood there behind it and watched it and it were trembling like a fiddle string. I says to Tommy Almond, get this engine stopped quick! He says I’ll have to go round and tell the tenants first. He’d about six tenants in you know and he were well loaded, he had about 1300hp on. I said reight oh Tommy, thee go and tell thi tenants and as soon as he went down t’ruddy steps Newton went round to the governor and pulled the catch off and shut the stop valve. Th’engine stopped, tenants or no tenants and the flywheel shaft at the low pressure side were smoking.

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 90298

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

This the funny part about it, low pressure side of the shaft were smoking and young Tommy says “What’s up wi’ it Newton?” I said the bloody shaft’s broken. Oh heck he says. Anyhow I comes back to Barlick, leaves it stopped, can’t do owt wi’out tackle and I were there be meself so I gets me breakfast, gets a boiler suit on and a tie and gets straightened up. Gets me mate and a couple of labourers and off we went down. Takes some blocks and some chains. The first job we did was get some blocks and chains up and we lifted the caps on the main bearings, which we’d had off oft enough and we had ‘em off within an hour. I says, bar it round. Couldn’t find owt, perfect were them bearings, lovely shaft, beautiful shine on it, very few marks to say it had run knocking up a hundred years. I couldn’t find owt. I thought oh Pickles, tha’s dropped a reight clanger here, you’ve stopped two and a half thousand looms for nowt! Harry Crabtree were at one side and I were at the other side and I’d Charlie Bateman with me and another labourer. I says go on, bar it round again and I couldn’t find a damn thing, I looked in all the places like radius corner (In the cheeks of the journal, a common propagation point for a crack) and back o’t cranks and all that and I couldn’t find owt. So I went round to’t low pressure side, that one that’d been hot. I were wi’ Harry at the low pressure side and I says to him, I’ve dropped a reight clanger here haven’t I. He says it looks so, it isn’t often tha drops a clanger like this, what the hell have we stopped the mill for, but let’s face it Newton, what were making that bloody noise? Go on I says to young Tommy Almond, bar it round again. And little Charlie Bateman were stood at the side of the high pressure crank and t’barring engine were at the low pressure side. Tom went to the barring engine and started it up like, you know how you do. ‘Oh, what the hell’s he want it barring for again’ sort of attitude you know, whizzed steam on to it and it moved with a bit of a shudder and little Charlie, the other side, says oh Newton, come round here. I says What’s up Charlie? Well he says, it were like this cranks here and that cranks there, it were quartered you know, and he says I’m bloody sure when that crank moved at your side mine didn’t! I says arta certain? He says I’m bloody certain! That crank moved afore mine did. I says tha’s made my day, get that barring engine stopped. Harry, come on, get these eccentrics off at this side. The two eccentrics that worked, they were circular slide valves on, you know, were’t valves on that engine. They were Corliss high pressure but t’lows had circular piston valves in. What I mean by that it twisted ‘em round to the ports. They didn’t go up and down, it twisted ‘em round. (These cylinders were made in 1898 by John Petrie at Rochdale who favoured the big old-fashioned cylindrical slide valves.)

Anyhow I said let’s get these eccentrics off at this side, high pressure side. Because these two eccentrics were right up to one another and right up to the flywheel boss. You couldn’t get your rule down between the eccentrics and the boss, it had always been a fault with that thing. Well, they took a fair bit of getting off because they were big eccentrics, they’d be about three feet six inches in diameter. We got the straps off and fastened the rods up and then uncottered the middles and slid ‘em this way (away from the flywheel boss) up to the bearing, we’d about six inches of room to move ‘em. Harry looked over the top of the eccentrics and pulled his great big two foot out, Harry always had a two foot in his pocket, one of them old ones about and inch and a quarter wide and about three sixteenths of an inch thick that he had had since he was a lad. He just pulled it out of his pocket, opened it up to two foot and he says here we are Newton, sithee, here’s thee noise! And he shoved it right through the bloody shaft and pulled it out at the bottom.

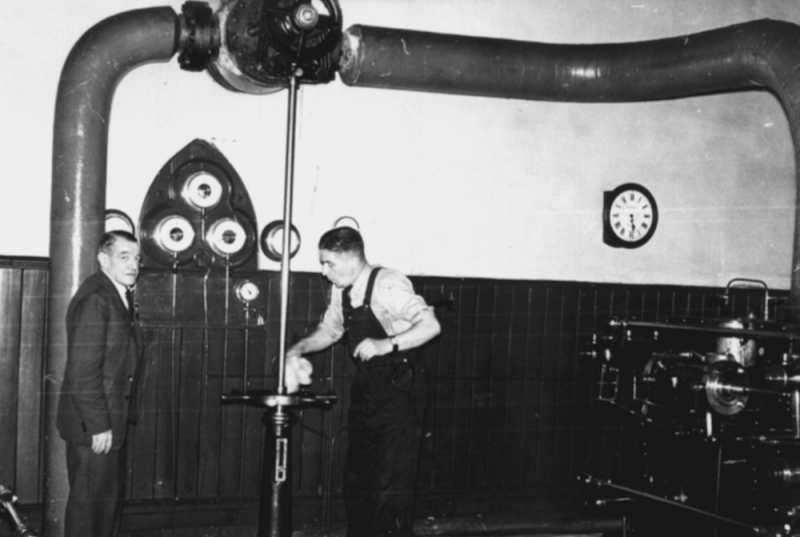

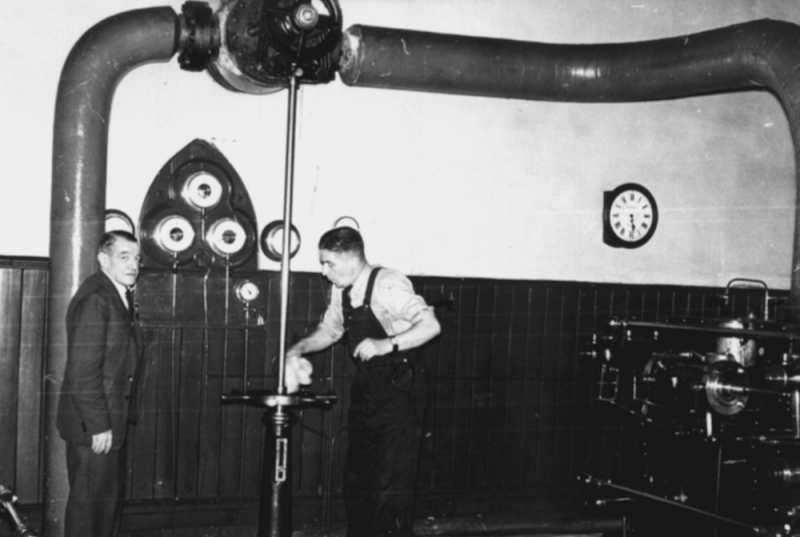

I think you have a picture somewhere of us stood on that pedestal with Harry and his two foot. I said to Harry, tha’s made my day! I don’t like anyone to be broken down but that’s made my ruddy day. I’ve been arguing with me father for a fortnight about this engine. It had just broken like you’d sawn it, it was straight as a die, you couldn’t have sawn it, you couldn’t have cut it with a flame torch owt like it, it were a hollow shaft, it had about a three and a half inch hole right through it. (It’s very common with shafts of this vintage for them to be bored right through the middle. This removed ‘piping’ which was an area of slag inclusion and weakness which could propagate cracks. This was a concomitant of the early technology of forging large shafts and the early engineers soon found that boring them in this way got rid of the starter zone for cracks and made the shafts more reliable.) It had just been hanging on with half an inch round the bore for ages, well, a fortnight anyway ever since the noise started. Anyway I get me father down and he were very quiet like and all the directors, they were quiet like.

“Give us an idea how long we’ll be stopped.” I says a fortnight. Me father says tha can’t put a shaft in this engine in a fortnight. Well I says, I were only trying to give them an idea, don’t tie me down to it. First of all he says, how are you going to get it out of the engine house? Oh I says, that’s one thing I hadn’t thought about. It won’t go past the low pressure cylinder and through the door not with a crank on it won’t. We’re talking now about three and a half or four ton you know, even with the broken pieces off. Oh I says, don’t worry, I wonder if them tenants in the shed down there’ll shift me some looms? The engine house windows overlooked the shed in the bottom. No travelling crane or owt like that you know. Why he says, what you going to do with it? I says I’m going to take the roof off and drop it into t’shed. I can put a girder up and put it through one of these windows and put a carriage on it to hang the blocks on, get hold of it in here, when I get it out take it over the top of the shed and drop it down into the shed with me long lift blocks on to the truck. I’ll never forget this, he says “Which truck arta going to use, that wi’t rubber tyres or that wi’t iron wheels, ‘cause if tha uses that wi’t rubber wheels I think they’ll go flat!” He he he! So that put us on like a friendly footing again. He must have thought I were barmy or sommat ‘cause we had a bloody truck, it’d carry about fifty ton, he made it years and years ago. I’ll just explain this truck, it were about six foot long and five foot wide and the top boards were four inch thick railway sleepers, all bolted on to some iron brackets that formed the frame and they were made out of three be one steel, and t’wheels were eighteen inches diameter and about five inches wide, they must have weighed a couple of hundredweight apiece and it used to take six of us to pull it down the yard empty! He he he, Old Johnny’s truck. Anyway it came in handy for jobs like that I’ll tell you, nobody were afraid of the truck collapsing! But beauty of it were they’d only put a piece of inch and a half leather loom belt on it to pull it wi’ at t’front! Anyhow we worked night and day and we got the flywheel jacked up (It was 22ft 6” diameter and weighed at least 45 tons).

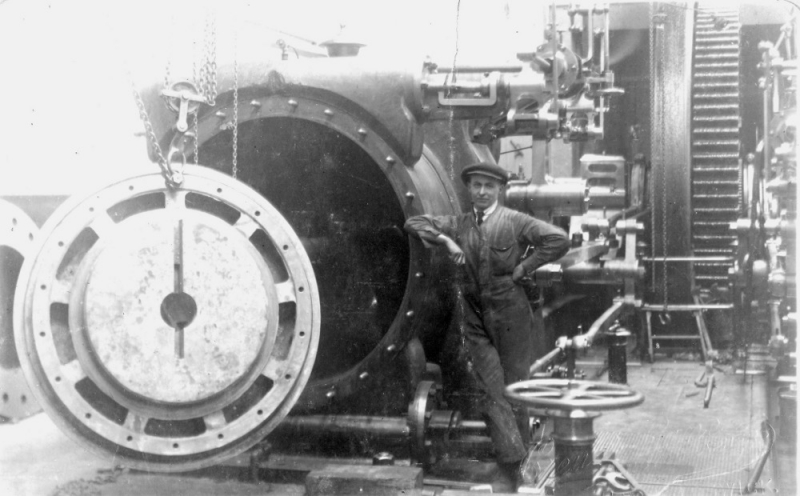

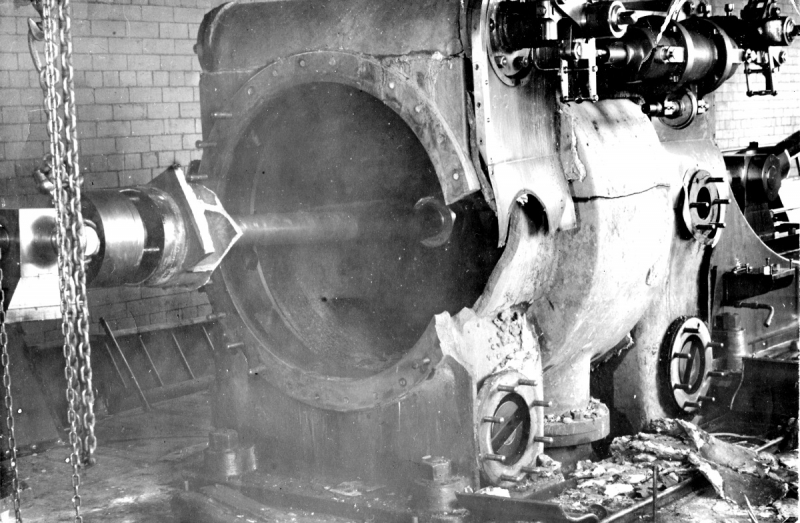

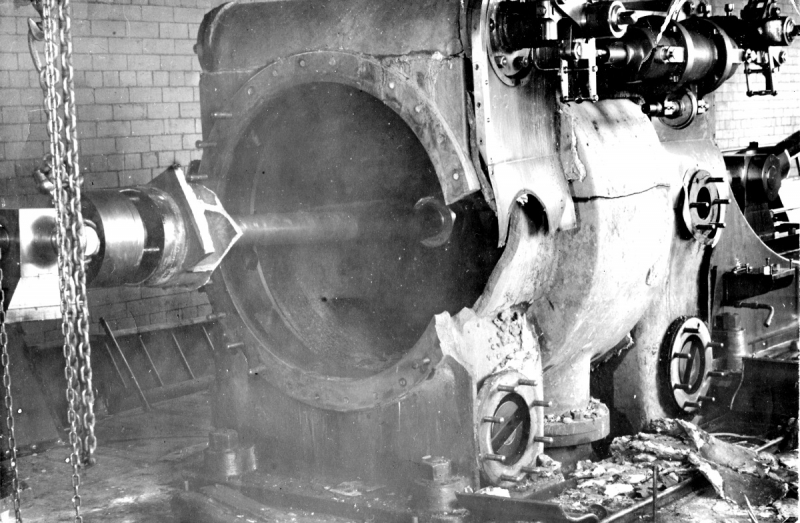

Newton, fag in mouth, watches Harry Crabtree pushing his big two foot rule through the shaft. Isn't it good that someone did the picture!

Anyhow I said let’s get these eccentrics off at this side, high pressure side. Because these two eccentrics were right up to one another and right up to the flywheel boss. You couldn’t get your rule down between the eccentrics and the boss, it had always been a fault with that thing. Well, they took a fair bit of getting off because they were big eccentrics, they’d be about three feet six inches in diameter. We got the straps off and fastened the rods up and then uncottered the middles and slid ‘em this way (away from the flywheel boss) up to the bearing, we’d about six inches of room to move ‘em. Harry looked over the top of the eccentrics and pulled his great big two foot out, Harry always had a two foot in his pocket, one of them old ones about and inch and a quarter wide and about three sixteenths of an inch thick that he had had since he was a lad. He just pulled it out of his pocket, opened it up to two foot and he says here we are Newton, sithee, here’s thee noise! And he shoved it right through the bloody shaft and pulled it out at the bottom.

I think you have a picture somewhere of us stood on that pedestal with Harry and his two foot. I said to Harry, tha’s made my day! I don’t like anyone to be broken down but that’s made my ruddy day. I’ve been arguing with me father for a fortnight about this engine. It had just broken like you’d sawn it, it was straight as a die, you couldn’t have sawn it, you couldn’t have cut it with a flame torch owt like it, it were a hollow shaft, it had about a three and a half inch hole right through it. (It’s very common with shafts of this vintage for them to be bored right through the middle. This removed ‘piping’ which was an area of slag inclusion and weakness which could propagate cracks. This was a concomitant of the early technology of forging large shafts and the early engineers soon found that boring them in this way got rid of the starter zone for cracks and made the shafts more reliable.) It had just been hanging on with half an inch round the bore for ages, well, a fortnight anyway ever since the noise started. Anyway I get me father down and he were very quiet like and all the directors, they were quiet like.

“Give us an idea how long we’ll be stopped.” I says a fortnight. Me father says tha can’t put a shaft in this engine in a fortnight. Well I says, I were only trying to give them an idea, don’t tie me down to it. First of all he says, how are you going to get it out of the engine house? Oh I says, that’s one thing I hadn’t thought about. It won’t go past the low pressure cylinder and through the door not with a crank on it won’t. We’re talking now about three and a half or four ton you know, even with the broken pieces off. Oh I says, don’t worry, I wonder if them tenants in the shed down there’ll shift me some looms? The engine house windows overlooked the shed in the bottom. No travelling crane or owt like that you know. Why he says, what you going to do with it? I says I’m going to take the roof off and drop it into t’shed. I can put a girder up and put it through one of these windows and put a carriage on it to hang the blocks on, get hold of it in here, when I get it out take it over the top of the shed and drop it down into the shed with me long lift blocks on to the truck. I’ll never forget this, he says “Which truck arta going to use, that wi’t rubber tyres or that wi’t iron wheels, ‘cause if tha uses that wi’t rubber wheels I think they’ll go flat!” He he he! So that put us on like a friendly footing again. He must have thought I were barmy or sommat ‘cause we had a bloody truck, it’d carry about fifty ton, he made it years and years ago. I’ll just explain this truck, it were about six foot long and five foot wide and the top boards were four inch thick railway sleepers, all bolted on to some iron brackets that formed the frame and they were made out of three be one steel, and t’wheels were eighteen inches diameter and about five inches wide, they must have weighed a couple of hundredweight apiece and it used to take six of us to pull it down the yard empty! He he he, Old Johnny’s truck. Anyway it came in handy for jobs like that I’ll tell you, nobody were afraid of the truck collapsing! But beauty of it were they’d only put a piece of inch and a half leather loom belt on it to pull it wi’ at t’front! Anyhow we worked night and day and we got the flywheel jacked up (It was 22ft 6” diameter and weighed at least 45 tons).

Newton, fag in mouth, watches Harry Crabtree pushing his big two foot rule through the shaft. Isn't it good that someone did the picture!

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 90298

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

But let’s finish that tale here, what had saved that engine from a complete smash-up running wi’ all that load on had been them two pinions set at a third of the circumference because she’d just dropped into the bottom of the teeth and stopped there. (The pinion gearing was the same width as the rim gear on the flywheel, 15”.) And she must have been in the bottom of the teeth for a fortnight, and that were the different noise we were hearing. With being machine cut wheels them teeth ‘ud go right into t’bottom. She’d ridden on the bottom of the teeth so the wheel didn’t go down into the cellar and jam anything up you know. It didn’t get hot in the second motion, it’s a wonder they didn’t get hot. First intimation they had that morning were the low pressure main bearing getting hot because of all the extra pressure there were on it. The high pressure bearing were just hanging on wi’ nothing, just going round. It were still driving the mill you know. I couldn’t understand that, it were a miracle, it still kept going on going round, high pressure crank and low so it must have been low pressure and intermediate that were running the mill. It must have been and yet his back pressure gauges had never shown any difference for a fortnight, his compound pressure. (The pressure gauge that showed the effective pressure on the low pressure cylinders rather than boiler pressure. They also measure vacuum if the engine is running light.)

Anyway we got it out and we got it into the shop and we put it on the borer to take the crank off that were on the broken end and I bored the shaft out of the other one. (When a component is going to be sacrificed, like a seized piston in a cylinder, the best way to separate the parts is to bore the damaged one out. That way you do no further damage.) We did all this at nights while we were waiting for the forging. I fetched the forging from Webb’s at Bury and it were red hot, it were sizzling, they put it on some steel girders for me at Webb’s, fastened it on wi’ some chains and I brought it red hot and it were drizzling wi’ rain. I’ll bet everybody thowt the wagon were on fire when I were coming through Burnley, all steaming up. It were like the rest of them, you got ‘em here on Saturday and you might as well have gone for it on Monday. We couldn’t turn it till Sunday night when we got cracking, it were too hot. We got it in’t lathe and we got it on top of the bed but it were too hot to begin turning. We started turning it at Sunday night, I worked on nights, me and Harry Crabtree. We were turning t’shaft, we also had the old broken shaft on the borer and we were boring the ends out. What I mean wi’th’ends, we bored the old shaft out (of the cranks) to save unshrinking ‘em. We didn’t want to warm ‘em unduly. You might as well bore ‘em out, you’ve plenty of time and them cranks weighed two ton apiece. They were seven foot stroke you know, eight or eight foot six. They were a hell of a length were them.

I asked Newton about machining the forging. “That forging you brought back from Webb’s. Just to get down to the technicalities of the job a bit, that forging ‘ud have a fair skin on it.” Oh aye, a lot of scale. “Now the first roughing cut down that like, what would you do that with?” Ordinary high speed steel. “You take your first cut so you were going down under the skin into the metal.” Aye, we’d a fair lathe. Get under the skin, scale ud be flying up on to the top of the tool box! We’d have about five eighths a side on the tool, as much as the lathe ud drive. “Five eighths a side! How deep were you going, an inch?” Aye well there’d be about an inch and a half or two inch to come off it uniform, you know, pretty uniform. Uniform at t’side o’t forging. “So you were taking a cut about half an inch deep?” We were lessening the diameter an inch. You know it were an irregular shape were that forging, there were the flats you know. But on the corners of your flats you’d got half an inch or five eighths of cut on the first time down. “That swarf ud be coming off in bloody lumps!” Oh it were blue and big lumps aye! (Blue because of the heat generated by the cut.)

Newton again. “I got into a bit of bother wi’ me swarf you see. You see when you’ve flats on your turnings come off in bits, but when you’ve been up once and you grind your tool up and you get a right rake on and get another half an inch of cut off they come off all curly and each turning when it breaks off is nearly as much as a man can lift when it gets cold enough! At Sunday night we had a damn good do and we’d a fair lot of turnings on Monday morning when Sidney come on the lathe. We put Sidney on the lathe during the day ‘cause he was a damn good turner were Sid. But I allus seemed to manage to get the night job. Now all these turnings were piled up behind the door you see so we had a chap on that used to move turnings and he shifted ‘em and then Sidney turned all day. Now he’d more or less be just taking the rough off like I were, taking the scale off. On Monday night it were starting to look like a shaft, it had got clean then so Newton comes in, grinds up (re-sharpened his cutting tool) and gets some cut on. At Tuesday morning Sidney comes in about quarter to seven, best to come in sooner and then if the other turner has anything to tell you it’s better than leaving notes. He could see where I were like and he says “Oh, I’m all right for today.” I’d only be about half way up it. The chap came in and shifted the turnings and when I came in at seven o’clock that night Sidney said I had a hell of a job wi’ Old Tommy this morning! I says Why? He said he went home, he threatened he were going to chuck up, it were your father that fetched him back. I said what the hell had he chucked up for? You see what we did we raked all the turnings from under the lathe and piled ‘em behind the door and when he came in at morning and saw the pile of turnings that I’d made during the night he says I’m not having this! ‘Cause we were allus pulling his leg you know. He says “Yon bugger’s fetched all the turnings back in that I took out yesterday morning!” So he went home! Anyhow, we got the job done. Now the biggest nightmare to me with that engine were, although I’d done all this before but not on so big a scale, were when I’d finished the flywheel shaft and I’d to put it back in the flywheel. This engine weren’t a staked wheel, it were a plug fit. What I mean to say is that the shaft were the same size as the bore of the flywheel. (This is not common. Flywheel bosses are usually bored bigger than the shaft so that they can be temporarily fitted with staking wedges before fitting the final permanent stakes on the flats. Notice that earlier when Newton was talking about refitting the pinion in the cellar it wasn’t a plug fit and he used wedges to hold the pinion in position on the second motion shaft. The flywheel had keyways cut in it and the shaft had flats to match these keyways but fitted the bore perfectly.) So we made gauges to fit the flywheel bore, it had been a bit slack on the old shaft so I made some gauges to the bore and we made it a better fit. But it had six keys in, not four, but you see with doing that and making it a plug fit it made the keys a bit lighter. The keys were only about three and a half inches wide and about two feet long, six keyways in the boss and six flats on the shaft. So anyhow, we got flywheel shaft back in, cut it a bit shorter and got, no need to true the wheel, just set it in position in the pinions and get it keyed on, put six new keys in. (Three keys from each side of the boss.) Then it comes doesn’t it, we had to put the cranks back on, these bloody great cranks at two tons apiece.

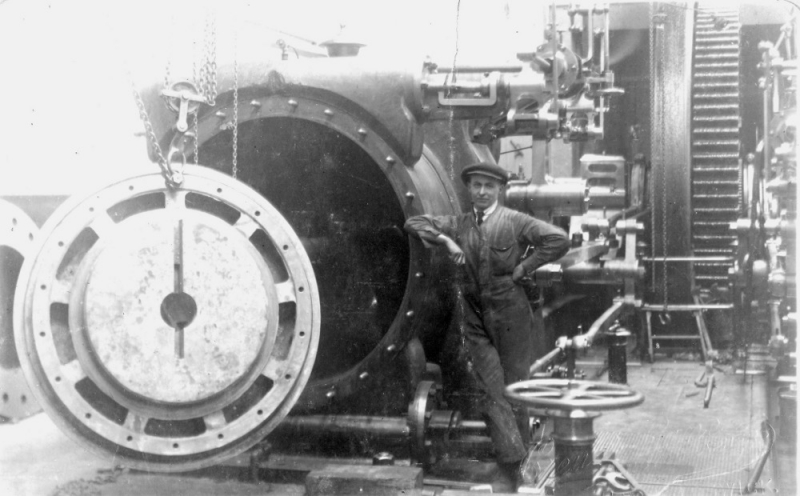

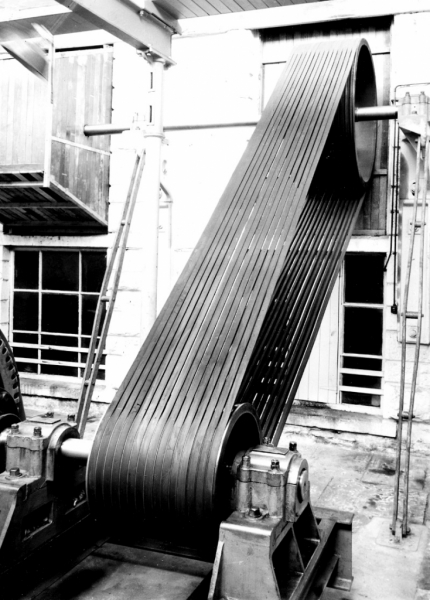

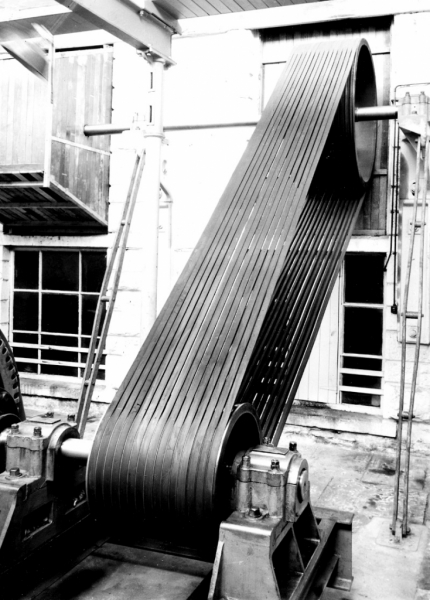

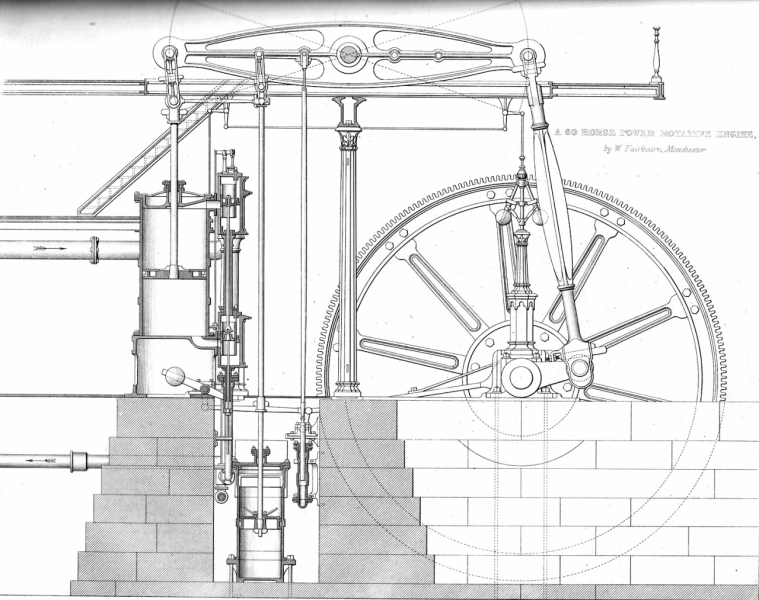

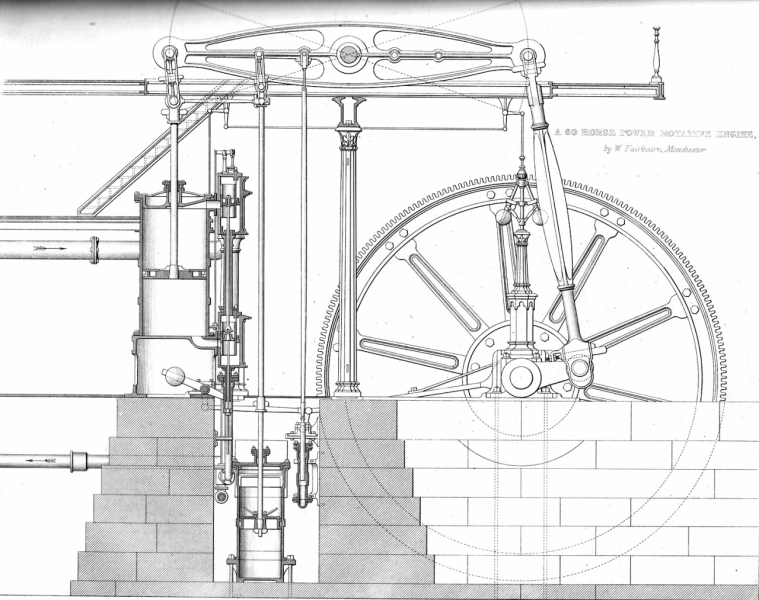

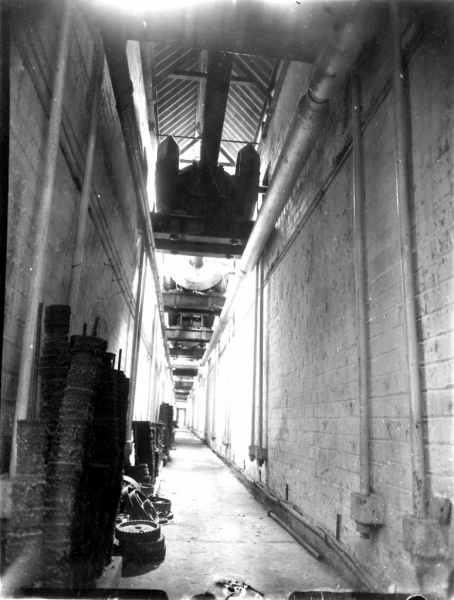

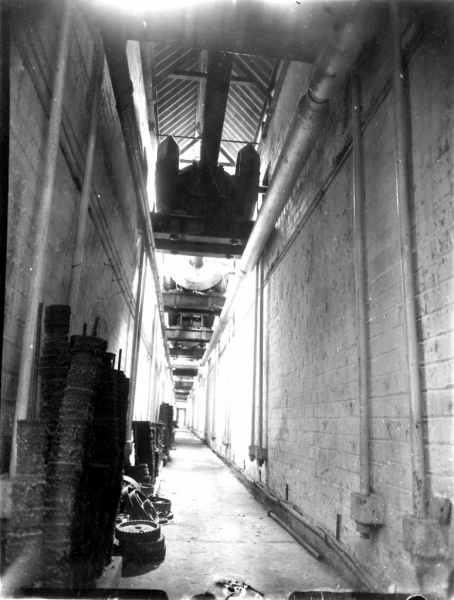

I'm not certain but I think this is the skyhook that Newton erected to get the shaft out and into the weaving shed.

Anyway we got it out and we got it into the shop and we put it on the borer to take the crank off that were on the broken end and I bored the shaft out of the other one. (When a component is going to be sacrificed, like a seized piston in a cylinder, the best way to separate the parts is to bore the damaged one out. That way you do no further damage.) We did all this at nights while we were waiting for the forging. I fetched the forging from Webb’s at Bury and it were red hot, it were sizzling, they put it on some steel girders for me at Webb’s, fastened it on wi’ some chains and I brought it red hot and it were drizzling wi’ rain. I’ll bet everybody thowt the wagon were on fire when I were coming through Burnley, all steaming up. It were like the rest of them, you got ‘em here on Saturday and you might as well have gone for it on Monday. We couldn’t turn it till Sunday night when we got cracking, it were too hot. We got it in’t lathe and we got it on top of the bed but it were too hot to begin turning. We started turning it at Sunday night, I worked on nights, me and Harry Crabtree. We were turning t’shaft, we also had the old broken shaft on the borer and we were boring the ends out. What I mean wi’th’ends, we bored the old shaft out (of the cranks) to save unshrinking ‘em. We didn’t want to warm ‘em unduly. You might as well bore ‘em out, you’ve plenty of time and them cranks weighed two ton apiece. They were seven foot stroke you know, eight or eight foot six. They were a hell of a length were them.

I asked Newton about machining the forging. “That forging you brought back from Webb’s. Just to get down to the technicalities of the job a bit, that forging ‘ud have a fair skin on it.” Oh aye, a lot of scale. “Now the first roughing cut down that like, what would you do that with?” Ordinary high speed steel. “You take your first cut so you were going down under the skin into the metal.” Aye, we’d a fair lathe. Get under the skin, scale ud be flying up on to the top of the tool box! We’d have about five eighths a side on the tool, as much as the lathe ud drive. “Five eighths a side! How deep were you going, an inch?” Aye well there’d be about an inch and a half or two inch to come off it uniform, you know, pretty uniform. Uniform at t’side o’t forging. “So you were taking a cut about half an inch deep?” We were lessening the diameter an inch. You know it were an irregular shape were that forging, there were the flats you know. But on the corners of your flats you’d got half an inch or five eighths of cut on the first time down. “That swarf ud be coming off in bloody lumps!” Oh it were blue and big lumps aye! (Blue because of the heat generated by the cut.)

Newton again. “I got into a bit of bother wi’ me swarf you see. You see when you’ve flats on your turnings come off in bits, but when you’ve been up once and you grind your tool up and you get a right rake on and get another half an inch of cut off they come off all curly and each turning when it breaks off is nearly as much as a man can lift when it gets cold enough! At Sunday night we had a damn good do and we’d a fair lot of turnings on Monday morning when Sidney come on the lathe. We put Sidney on the lathe during the day ‘cause he was a damn good turner were Sid. But I allus seemed to manage to get the night job. Now all these turnings were piled up behind the door you see so we had a chap on that used to move turnings and he shifted ‘em and then Sidney turned all day. Now he’d more or less be just taking the rough off like I were, taking the scale off. On Monday night it were starting to look like a shaft, it had got clean then so Newton comes in, grinds up (re-sharpened his cutting tool) and gets some cut on. At Tuesday morning Sidney comes in about quarter to seven, best to come in sooner and then if the other turner has anything to tell you it’s better than leaving notes. He could see where I were like and he says “Oh, I’m all right for today.” I’d only be about half way up it. The chap came in and shifted the turnings and when I came in at seven o’clock that night Sidney said I had a hell of a job wi’ Old Tommy this morning! I says Why? He said he went home, he threatened he were going to chuck up, it were your father that fetched him back. I said what the hell had he chucked up for? You see what we did we raked all the turnings from under the lathe and piled ‘em behind the door and when he came in at morning and saw the pile of turnings that I’d made during the night he says I’m not having this! ‘Cause we were allus pulling his leg you know. He says “Yon bugger’s fetched all the turnings back in that I took out yesterday morning!” So he went home! Anyhow, we got the job done. Now the biggest nightmare to me with that engine were, although I’d done all this before but not on so big a scale, were when I’d finished the flywheel shaft and I’d to put it back in the flywheel. This engine weren’t a staked wheel, it were a plug fit. What I mean to say is that the shaft were the same size as the bore of the flywheel. (This is not common. Flywheel bosses are usually bored bigger than the shaft so that they can be temporarily fitted with staking wedges before fitting the final permanent stakes on the flats. Notice that earlier when Newton was talking about refitting the pinion in the cellar it wasn’t a plug fit and he used wedges to hold the pinion in position on the second motion shaft. The flywheel had keyways cut in it and the shaft had flats to match these keyways but fitted the bore perfectly.) So we made gauges to fit the flywheel bore, it had been a bit slack on the old shaft so I made some gauges to the bore and we made it a better fit. But it had six keys in, not four, but you see with doing that and making it a plug fit it made the keys a bit lighter. The keys were only about three and a half inches wide and about two feet long, six keyways in the boss and six flats on the shaft. So anyhow, we got flywheel shaft back in, cut it a bit shorter and got, no need to true the wheel, just set it in position in the pinions and get it keyed on, put six new keys in. (Three keys from each side of the boss.) Then it comes doesn’t it, we had to put the cranks back on, these bloody great cranks at two tons apiece.

I'm not certain but I think this is the skyhook that Newton erected to get the shaft out and into the weaving shed.

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 90298

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

I’d had it on me mind ever since I’d started the job about putting the cranks on. I gave ‘em fourteen thou of nip, which is a hell of a lot. What I mean by that is I turned the shaft fourteen thou bigger than the hole in the crank and the shaft were about fifteen inch diameter. The cranks would be about nine inch thick, I were going to say ten but I’ll say nine inch, it’s a hell of a crank that’s nine inches wide. But they were big cranks and I thought now then, I’ve that bugger to warm now and I’ve got to shrink them on to there and get ‘em in the right place with only one keyway in. (The only hold the cranks had on the shaft was the grip created by shrinkage. The cranks were set ninety degrees apart, with the LP crank leading the HP in order to quarter the engine. It was essential to make sure that when fitted the crank was oriented properly and in order to locate it a single dummy key was used. It was called a ‘dummy’ because it had no part in stopping the crank moving on the shaft, this was entirely due to the grip of the crank generated by it shrinking. This is why Newton made the shaft .0014” bigger than the bore in the crank and is also why the crank had to be heated so as to expand the bore so the crank would go on. Sorry about the lecture but many people will not understand what Newton was doing.)

We got all the tackle up and had a practice run with one crank before we started heating it. What I mean by a practice run, you get all your blocks in the correct position, one set where you’re going to put it to warm it and another set over the shaft where you’re going to transfer it to shove it on. Now them blocks over your shaft, you don’t leave any chances. They’re set in position where that crank’ll go on to that shaft without anybody touching that chain at all. Just take it off the first pair of blocks after using them to adjust the height, straight on to the other and on to the shaft. No bloody pulling or saying up a bit and down a bit, transfer it and shove it straight on. So we started warming just after tea I don’t know what day it was. We’d two sets of rose jets on oxygen and acetylene and I think I’d about ten bottles of each outside and also we’d two great big paraffin blow lamps that we’d had for years and I got them down there as well. (Something Newton doesn’t mention is that one problem that can be encountered using oxy-acetylene is that when large volumes of gas are being used for big pepper-pot burners the cylinders cool down as the gas pressure drops, the same principle as a refrigeration plant, and you have to be ready to swap from one cylinder to another so that the cold cylinder can regain some temperature. This is why caravan owners use propane instead of Calor gas in winter because Calor gas freezes at a higher temperature than propane.) We built an asbestos cupboard round the crank, packed it up on firebricks and we started warming it. About one o’clock in the morning the gauge ud just about go in, by the gauge going in I mean I’d made a gauge to the diameter of the shaft with a handle on it so’s we could try it in the crank as we were warming it. At one o’clock it decided to go in the bore of the crank and we’d been blowing at it for like five or six hours. At about two o’clock Harry says, it’ll go on now Newton. I says aye, it will. It had about two inch of travel, by two inch of travel I mean when you put your gauge point on at one end it’d travel two inch from side to side at the other. He said it’ll go on now. I said, We’ll give it another half an hour Harry.”

I asked Newton to explain his gauge because not many people use this method these days. (A pointed steel rod fractionally less than the bore you are measuring.) “If you hold the point of your gauge on the bottom of the bore you can move it across about two inches at the top. That’s what we call travel on the gauge. Now that two inches is equivalent to about ten or fifteen thou of tolerance which made that bore ten or fifteen thou bigger than the shaft. So Harry knew, he’d been with me before on these big jobs, he says it’ll go now and I said give it another half an hour, we’ll get it as big as we can. It were glowing red this two ton of metal. So we blew at it till I think about half past two. I said let’s not take any chances. When you’re warming something like that you allus get some scale forming so I had a wire brush handy to de-scale it before you push it on. Then we just picked it up and transferred it off one set of blocks on to t’other. There were four of us, I’m emphasising that because you were better wi’ four than you were wi’ bloody ten because if you’ve too many men about things happen. You have a clip round it, a special clip so you could have one man one side and one at t’other to keep it straight. When you transfer it to the final set of blocks you’ve two pieces of two inch shafting handy, me at one side and Harry at t’other ready to push it on the cheeks to shove it straight on. At the same time you have a dummy key on a handle so you don’t burn yourself and as soon as it’s on you pop that in to make sure it’s lined up right. (This was to ensure that the cranks were in their correct positions when both had been installed, 90 degrees to each other. Usually the low pressure was set 90 degrees in front of the high pressure.) Believe me or believe me not it went straight on Stanley, it just slid up the shaft straight up to the collar, key in and drop the weight on it. What I mean by that is we slacked the block to let the weight of the crank drop on the shaft to stop it sliding about on its own when we let go. I bet that crank weren’t three minutes by any clock in the world before hell wouldn’t have shifted it, it had shrunk that sharp on to the cold shaft you know. (Newton doesn’t mention it but once the crank had nipped on the shaft, the dummy key with the handle is removed for use on the other crank. The keyway that is left is filled with a dummy key made to fit. It’s called a dummy because it isn’t actually doing anything, the nip on the shaft is more than adequate to hold the crank.)

Aye, the lads were suited, I can see ‘em yet, they were really chuffed with that crank being on but I soon stopped ‘em from laughing! There were a sink in the engine house and they all went to the sink when I said reight lads, a bit of supper now! Like, that’s it, we’ll run home now. I didn’t tell them for how long though. They all went to the sink to wash off you know, off wi’t overalls and hang ‘em up. So I went to the sink to have a wash and Crabby knew, he knew did Harry. I went up to t’sink and then I says Aye, that’s right lads. Get theselves weshed, you’ve done a good job, get theselves off home and be back in an hour! He he he! That were three o’clock in the morning. Eh what? Well I says, you don’t think I’m going to bed wi’ one crank on and the other off do you? Not likely. I’ll go to bed when the other bugger’s on. Anyway, we got the other on be dinnertime and then I let ‘em have the afternoon off. I think they’d been out long enough, two days. We were running on Friday, we’d been stopped, well we weren’t really stopped a fortnight, we were running at Friday and the mill went into production on Monday morning. It never ailed another thing didn’t that engine as far as any major operations were concerned. No teething troubles, no hot bearings, nothing at all.”

I asked Newton if it ran different afterwards. “It run quieter. It allus had a bit of a fault, when I come to set the flywheel in position to key it on I noticed that one pinion had been running about three eighths over the edge of the teeth. Well, you can’t set a flywheel to two that’s staggered. So what I did I set it to the back one which was the most awkward to get at. I set it in line with the back one and I left the front one where it were and it ran till Earby holidays and then I went down with Harry Crabtree and young Jimmy Fort and we knocked the keys back and moved it into line so they were both in line. But otherwise it never give any trouble didn’t pinion being three eighths out of line but it had been out of line t’other way before. What they couldn’t see was that with running out of line it had worn some ledges on the back pinion so while we were doing the big job I set a labourer on to file the ledges out of the pinion and I lined it up with that wheel ‘cause the front one were easier to get at. That were the last major operation that were done on that engine apart from the usual, take up the crankpin bearing or take the beam trunnions up, you know, bits of things like that.

It ran a lot you know at the end of its life. It ran from seven in the morning until ten at night. (Housewife’s shift, six till ten.) He went and got blooming mumps did th’engineer and I went down ‘cause I were the only one that could run it apart from him. He were only a young chap were Tom then. I ran it from seven in the morning until ten at night for about seven or eight bloody week. I thought they were only off a day or two wi’ mumps and I says to a doctor friend of mine I’m running that bloody engine at Earby, how long does it take ‘em to come back wi’ mumps? He says how old is he Newton? Oh I says, forty one or forty two. Oh Christ he says, he’ll be months! Bloody dangerous is mumps when thart forty five, it can stop thee from getting childer! I didn’t know that. Anyway the boss came one afternoon, Captain Smith frae Colne and I’m stood on’t balcony like, looking down the yard and looking a bit sorry for meself. He came out to me on the balcony, he were a nice chap and I could get on wi’ him, a lot of people couldn’t but I could because I used to be straight wi’ the feller. I just turned to him and I said How long’s this bloody caper going to be going on? He says what do you mean Newton? Are you having some trouble? I says no but isn’t it a ruddy long while from getting up at half past five in the morning to going home at quarter to eleven at night from here? He says What? Well I says, you know you’ve a night shift running here while ten o’clock? I’m running the night shift, t'other feller were all right weren’t he, he came at half past six and three nights a week he went home at half past five and Joe Plushy (A dialect term for a ‘fall guy’.) were running it while ten. He says oh blooming heck Newton, I never thought of that! You’re not going to give up are you and leave us all stopped? No, I said, I’m not going to give up but I were there six or seven week wi’ t’mumps job. I didn’t think anybody could get mumps and stop off work seven week.”

I asked Newton about something he had told me one day in a conversation. “I think I once heard you talk about that and you said that when you went down the first time on relief you had a bit of bother with the stokers.” Newton again, “Oh, second morning. First day I had a bit of bother ‘cause t’steam were down and all that, you go down into the boiler house and you get ‘em to steam up and your troubles are over that doesn’t happen no more. But when I went down the second morning, no fireman, he hadn’t turned up and I hung about and hung about because th’oiler didn’t come till ten to seven because he only got paid from that time and he didn’t come so I’d to get down into the boiler house and waken the boilers up. I set on wi’ only fifty five pound of steam and two thousand loom running. He he he! (The normal practice at Victoria because of the heavy load was to have all the boilers up to 160psi and blowing off when the engine started.) Anyhow he comes trailing in at ten past eight and of course he did this three days in one week. I started to complain about this and they threatened to sack him and the boss came and anyhow they got me a bloke to fire at night that came from Colne and he were a moulder (In a foundry). Now he were a right case he were, that moulder. He came dashing up one night and he says Newton, you’d better come down quick! I said What’s to do? He said I think I’ve getten too little water in one boiler, I can’t see it in the gauge! I flew down them steps ‘cause it weren’t so long before they’d had a set of tubes down because of running without water you know. I flew down them steps and I listened to me blooming engine and I thought it’s a bit queer is this. So I went down into t’boiler house and never mind the boiler being blooming empty, it were full reight up to t’lid! He he he! Anyhow he had a good head of steam so I cracked the blow-down valve at the bottom of the boiler and watched it come out into the dam about as thick as your wrist and it were half an hour before it came into the bloody glass. Course, I daren’t open it full do because we’d only one boiler on. It were about an hour and a half before it started showing in the glass. Now there were one advantage there of course, that engine were about ten or fifteen feet higher than the boiler house or else we’d have been in a right mess there. But I flew up them stairs and opened me high pressure drains I can tell you.”

“So because of the height of the engine above the boiler any water that primed had a good chance of running back down the pipe?”

“Oh aye, well it would run down the pipe you see, it went straight up out of the boiler house and then across the yard and then up again and it had an expansion pipe up there where it went over into the stop valve like a big ‘U’ pipe and that took it up another two or three feet. It were full up to the lid, there’s no doubt about that and I daren’t open the blow-down too far wi’ all the looms I had running. I’d 600 looms running in Johnson’s shed. If I’d opened the blow off far enough to get rid of it in say ten to fifteen minutes, I’d have had no steam in the blinking boiler would I and the other boiler were banked up. So anyway, he didn’t do that any more didn’t that character.”

There were other smaller jobs at Victoria over the years and Brown and Pickles did all of them. Not all the jobs were on such a heroic scale, I have a copy of a letter dated September 2nd 1911 from W H Atkinson, architect and surveyor of Shaw Street in Colne who acted for the Mill Company. It was written to Henry Brown and Sons, Earby and accepted Brown’s tender for moving two tape machines, size becks, donkey engines and some other machinery in the warehouse for a re-organisation of the space. The price was £28-1-0 in old money. This sort of job was typical right up to the 1980s and what is interesting about this letter is that Atkinson is dealing with Henry Brown at Earby as a separate entity even though they had been established in Barlick for 11 years. This fits in with the constant references throughout the later history of the firm to the Browns having an enduring connection with the Earby. I often wonder whether it was never part of the Havre Park liquidation but that in reality Henry Brown and Sons in Albion Street at Earby survived far longer than I thought.

Brown and Pickles provided all sorts of services to the mills they serviced and sometimes it didn’t work in their favour. Another of my informants in the LTP, Horace Thornton, worked on the Big Mill engine for a couple of years after 1945 before becoming a taper for Johnsons. He told me about the load on the engine in 1945. They were burning 60 tons of coal a week in three boilers and the firebeater Charlie Sculthorpe was struggling, he wasn’t up to the job and Horace said they were frequently short of steam. Charlie got fed up and left to go to Armoride’s at Grove Shed in Earby for more money. Billy Lindsay was sent to Victoria from Bracewell’s Airebank Mill at Gargrave where he was firebeater. Only problem was that at the time Airebank Mill was only firing at 40psi for process steam and heat, the mill had been electrified. He was no better than Charlie so Johnny Pickles lent the Mill Company one of his men, Tommy Almond who was an expert firebeater. Tommy liked the job so well he stayed and in 1947 became engineer replacing Billy Lancaster. The Mill Company got a good man, Johnny lost one.

One more interesting thing about the engine. I have copies of indicator diagrams taken by the National Vulcan surveyor in May 1951 which show a vacuum of 26” water gauge. This is a good figure for an engine of this age. Newton loved the engine because in its later years, despite being the oldest engine in the district and very heavily loaded, in terms of coal burned and horse power delivered it was the most economical engine on Newton’s books. Not a bad record for an engine that ran for 107 years.

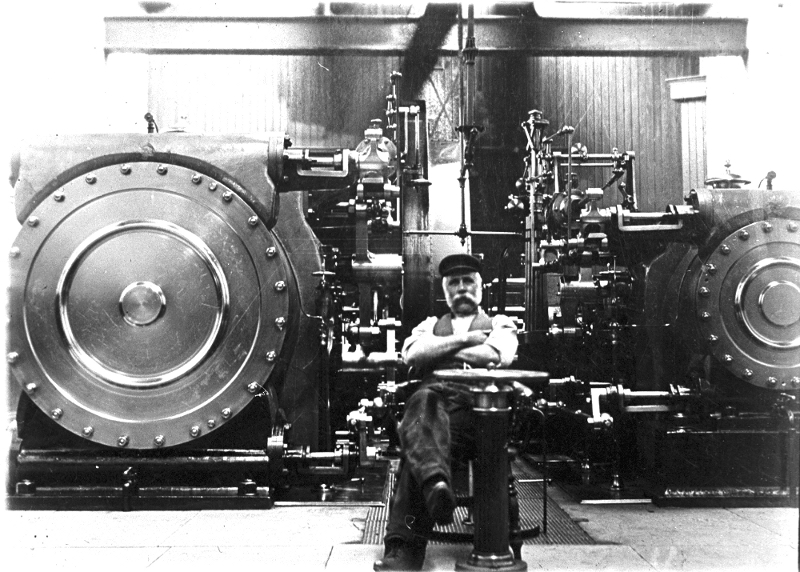

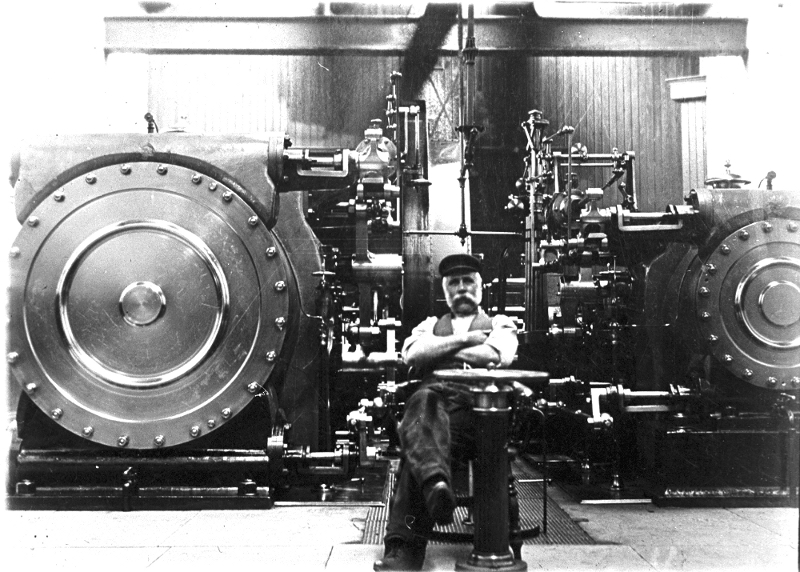

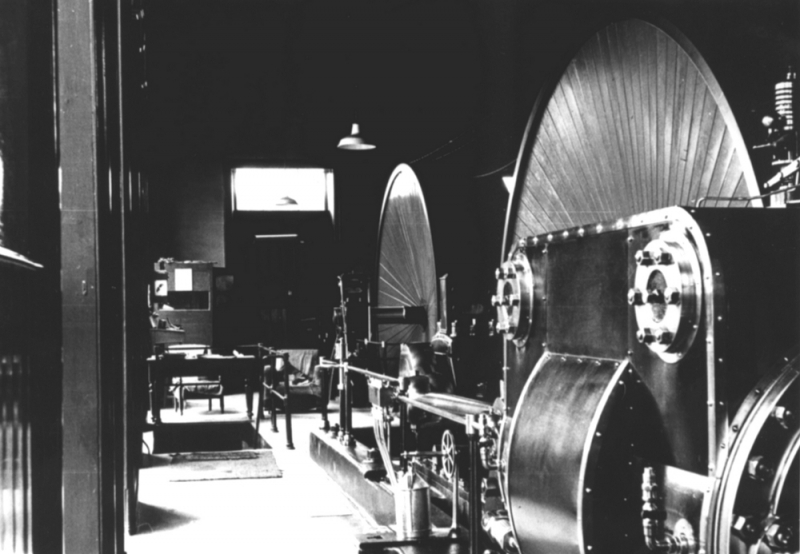

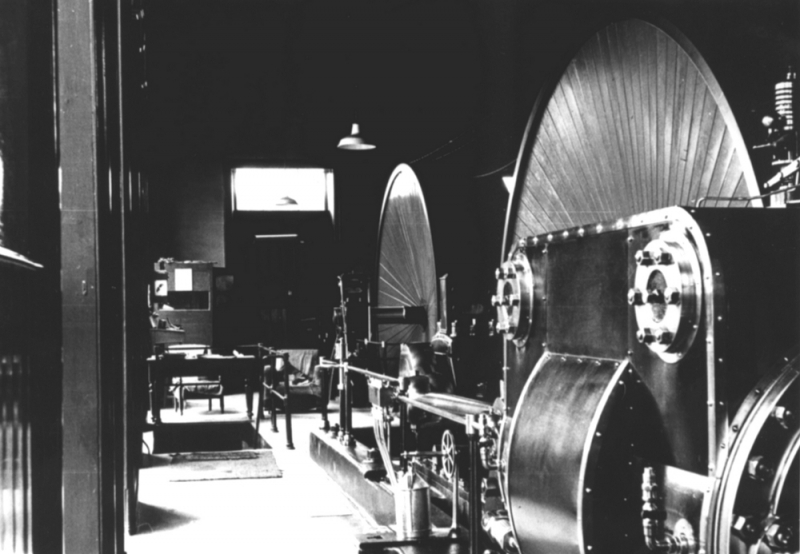

Victoria Mill, Earby in 1954, the broken fly shaft. Johnny Pickles is on the right and the man stood in front of him in the pin stripe suit is Teddy Woods from Procter and Procter at Burnley. I think the man behind Johnny is Tommy Almond who was engineer at the mill.

We got all the tackle up and had a practice run with one crank before we started heating it. What I mean by a practice run, you get all your blocks in the correct position, one set where you’re going to put it to warm it and another set over the shaft where you’re going to transfer it to shove it on. Now them blocks over your shaft, you don’t leave any chances. They’re set in position where that crank’ll go on to that shaft without anybody touching that chain at all. Just take it off the first pair of blocks after using them to adjust the height, straight on to the other and on to the shaft. No bloody pulling or saying up a bit and down a bit, transfer it and shove it straight on. So we started warming just after tea I don’t know what day it was. We’d two sets of rose jets on oxygen and acetylene and I think I’d about ten bottles of each outside and also we’d two great big paraffin blow lamps that we’d had for years and I got them down there as well. (Something Newton doesn’t mention is that one problem that can be encountered using oxy-acetylene is that when large volumes of gas are being used for big pepper-pot burners the cylinders cool down as the gas pressure drops, the same principle as a refrigeration plant, and you have to be ready to swap from one cylinder to another so that the cold cylinder can regain some temperature. This is why caravan owners use propane instead of Calor gas in winter because Calor gas freezes at a higher temperature than propane.) We built an asbestos cupboard round the crank, packed it up on firebricks and we started warming it. About one o’clock in the morning the gauge ud just about go in, by the gauge going in I mean I’d made a gauge to the diameter of the shaft with a handle on it so’s we could try it in the crank as we were warming it. At one o’clock it decided to go in the bore of the crank and we’d been blowing at it for like five or six hours. At about two o’clock Harry says, it’ll go on now Newton. I says aye, it will. It had about two inch of travel, by two inch of travel I mean when you put your gauge point on at one end it’d travel two inch from side to side at the other. He said it’ll go on now. I said, We’ll give it another half an hour Harry.”

I asked Newton to explain his gauge because not many people use this method these days. (A pointed steel rod fractionally less than the bore you are measuring.) “If you hold the point of your gauge on the bottom of the bore you can move it across about two inches at the top. That’s what we call travel on the gauge. Now that two inches is equivalent to about ten or fifteen thou of tolerance which made that bore ten or fifteen thou bigger than the shaft. So Harry knew, he’d been with me before on these big jobs, he says it’ll go now and I said give it another half an hour, we’ll get it as big as we can. It were glowing red this two ton of metal. So we blew at it till I think about half past two. I said let’s not take any chances. When you’re warming something like that you allus get some scale forming so I had a wire brush handy to de-scale it before you push it on. Then we just picked it up and transferred it off one set of blocks on to t’other. There were four of us, I’m emphasising that because you were better wi’ four than you were wi’ bloody ten because if you’ve too many men about things happen. You have a clip round it, a special clip so you could have one man one side and one at t’other to keep it straight. When you transfer it to the final set of blocks you’ve two pieces of two inch shafting handy, me at one side and Harry at t’other ready to push it on the cheeks to shove it straight on. At the same time you have a dummy key on a handle so you don’t burn yourself and as soon as it’s on you pop that in to make sure it’s lined up right. (This was to ensure that the cranks were in their correct positions when both had been installed, 90 degrees to each other. Usually the low pressure was set 90 degrees in front of the high pressure.) Believe me or believe me not it went straight on Stanley, it just slid up the shaft straight up to the collar, key in and drop the weight on it. What I mean by that is we slacked the block to let the weight of the crank drop on the shaft to stop it sliding about on its own when we let go. I bet that crank weren’t three minutes by any clock in the world before hell wouldn’t have shifted it, it had shrunk that sharp on to the cold shaft you know. (Newton doesn’t mention it but once the crank had nipped on the shaft, the dummy key with the handle is removed for use on the other crank. The keyway that is left is filled with a dummy key made to fit. It’s called a dummy because it isn’t actually doing anything, the nip on the shaft is more than adequate to hold the crank.)

Aye, the lads were suited, I can see ‘em yet, they were really chuffed with that crank being on but I soon stopped ‘em from laughing! There were a sink in the engine house and they all went to the sink when I said reight lads, a bit of supper now! Like, that’s it, we’ll run home now. I didn’t tell them for how long though. They all went to the sink to wash off you know, off wi’t overalls and hang ‘em up. So I went to the sink to have a wash and Crabby knew, he knew did Harry. I went up to t’sink and then I says Aye, that’s right lads. Get theselves weshed, you’ve done a good job, get theselves off home and be back in an hour! He he he! That were three o’clock in the morning. Eh what? Well I says, you don’t think I’m going to bed wi’ one crank on and the other off do you? Not likely. I’ll go to bed when the other bugger’s on. Anyway, we got the other on be dinnertime and then I let ‘em have the afternoon off. I think they’d been out long enough, two days. We were running on Friday, we’d been stopped, well we weren’t really stopped a fortnight, we were running at Friday and the mill went into production on Monday morning. It never ailed another thing didn’t that engine as far as any major operations were concerned. No teething troubles, no hot bearings, nothing at all.”

I asked Newton if it ran different afterwards. “It run quieter. It allus had a bit of a fault, when I come to set the flywheel in position to key it on I noticed that one pinion had been running about three eighths over the edge of the teeth. Well, you can’t set a flywheel to two that’s staggered. So what I did I set it to the back one which was the most awkward to get at. I set it in line with the back one and I left the front one where it were and it ran till Earby holidays and then I went down with Harry Crabtree and young Jimmy Fort and we knocked the keys back and moved it into line so they were both in line. But otherwise it never give any trouble didn’t pinion being three eighths out of line but it had been out of line t’other way before. What they couldn’t see was that with running out of line it had worn some ledges on the back pinion so while we were doing the big job I set a labourer on to file the ledges out of the pinion and I lined it up with that wheel ‘cause the front one were easier to get at. That were the last major operation that were done on that engine apart from the usual, take up the crankpin bearing or take the beam trunnions up, you know, bits of things like that.

It ran a lot you know at the end of its life. It ran from seven in the morning until ten at night. (Housewife’s shift, six till ten.) He went and got blooming mumps did th’engineer and I went down ‘cause I were the only one that could run it apart from him. He were only a young chap were Tom then. I ran it from seven in the morning until ten at night for about seven or eight bloody week. I thought they were only off a day or two wi’ mumps and I says to a doctor friend of mine I’m running that bloody engine at Earby, how long does it take ‘em to come back wi’ mumps? He says how old is he Newton? Oh I says, forty one or forty two. Oh Christ he says, he’ll be months! Bloody dangerous is mumps when thart forty five, it can stop thee from getting childer! I didn’t know that. Anyway the boss came one afternoon, Captain Smith frae Colne and I’m stood on’t balcony like, looking down the yard and looking a bit sorry for meself. He came out to me on the balcony, he were a nice chap and I could get on wi’ him, a lot of people couldn’t but I could because I used to be straight wi’ the feller. I just turned to him and I said How long’s this bloody caper going to be going on? He says what do you mean Newton? Are you having some trouble? I says no but isn’t it a ruddy long while from getting up at half past five in the morning to going home at quarter to eleven at night from here? He says What? Well I says, you know you’ve a night shift running here while ten o’clock? I’m running the night shift, t'other feller were all right weren’t he, he came at half past six and three nights a week he went home at half past five and Joe Plushy (A dialect term for a ‘fall guy’.) were running it while ten. He says oh blooming heck Newton, I never thought of that! You’re not going to give up are you and leave us all stopped? No, I said, I’m not going to give up but I were there six or seven week wi’ t’mumps job. I didn’t think anybody could get mumps and stop off work seven week.”

I asked Newton about something he had told me one day in a conversation. “I think I once heard you talk about that and you said that when you went down the first time on relief you had a bit of bother with the stokers.” Newton again, “Oh, second morning. First day I had a bit of bother ‘cause t’steam were down and all that, you go down into the boiler house and you get ‘em to steam up and your troubles are over that doesn’t happen no more. But when I went down the second morning, no fireman, he hadn’t turned up and I hung about and hung about because th’oiler didn’t come till ten to seven because he only got paid from that time and he didn’t come so I’d to get down into the boiler house and waken the boilers up. I set on wi’ only fifty five pound of steam and two thousand loom running. He he he! (The normal practice at Victoria because of the heavy load was to have all the boilers up to 160psi and blowing off when the engine started.) Anyhow he comes trailing in at ten past eight and of course he did this three days in one week. I started to complain about this and they threatened to sack him and the boss came and anyhow they got me a bloke to fire at night that came from Colne and he were a moulder (In a foundry). Now he were a right case he were, that moulder. He came dashing up one night and he says Newton, you’d better come down quick! I said What’s to do? He said I think I’ve getten too little water in one boiler, I can’t see it in the gauge! I flew down them steps ‘cause it weren’t so long before they’d had a set of tubes down because of running without water you know. I flew down them steps and I listened to me blooming engine and I thought it’s a bit queer is this. So I went down into t’boiler house and never mind the boiler being blooming empty, it were full reight up to t’lid! He he he! Anyhow he had a good head of steam so I cracked the blow-down valve at the bottom of the boiler and watched it come out into the dam about as thick as your wrist and it were half an hour before it came into the bloody glass. Course, I daren’t open it full do because we’d only one boiler on. It were about an hour and a half before it started showing in the glass. Now there were one advantage there of course, that engine were about ten or fifteen feet higher than the boiler house or else we’d have been in a right mess there. But I flew up them stairs and opened me high pressure drains I can tell you.”

“So because of the height of the engine above the boiler any water that primed had a good chance of running back down the pipe?”

“Oh aye, well it would run down the pipe you see, it went straight up out of the boiler house and then across the yard and then up again and it had an expansion pipe up there where it went over into the stop valve like a big ‘U’ pipe and that took it up another two or three feet. It were full up to the lid, there’s no doubt about that and I daren’t open the blow-down too far wi’ all the looms I had running. I’d 600 looms running in Johnson’s shed. If I’d opened the blow off far enough to get rid of it in say ten to fifteen minutes, I’d have had no steam in the blinking boiler would I and the other boiler were banked up. So anyway, he didn’t do that any more didn’t that character.”

There were other smaller jobs at Victoria over the years and Brown and Pickles did all of them. Not all the jobs were on such a heroic scale, I have a copy of a letter dated September 2nd 1911 from W H Atkinson, architect and surveyor of Shaw Street in Colne who acted for the Mill Company. It was written to Henry Brown and Sons, Earby and accepted Brown’s tender for moving two tape machines, size becks, donkey engines and some other machinery in the warehouse for a re-organisation of the space. The price was £28-1-0 in old money. This sort of job was typical right up to the 1980s and what is interesting about this letter is that Atkinson is dealing with Henry Brown at Earby as a separate entity even though they had been established in Barlick for 11 years. This fits in with the constant references throughout the later history of the firm to the Browns having an enduring connection with the Earby. I often wonder whether it was never part of the Havre Park liquidation but that in reality Henry Brown and Sons in Albion Street at Earby survived far longer than I thought.

Brown and Pickles provided all sorts of services to the mills they serviced and sometimes it didn’t work in their favour. Another of my informants in the LTP, Horace Thornton, worked on the Big Mill engine for a couple of years after 1945 before becoming a taper for Johnsons. He told me about the load on the engine in 1945. They were burning 60 tons of coal a week in three boilers and the firebeater Charlie Sculthorpe was struggling, he wasn’t up to the job and Horace said they were frequently short of steam. Charlie got fed up and left to go to Armoride’s at Grove Shed in Earby for more money. Billy Lindsay was sent to Victoria from Bracewell’s Airebank Mill at Gargrave where he was firebeater. Only problem was that at the time Airebank Mill was only firing at 40psi for process steam and heat, the mill had been electrified. He was no better than Charlie so Johnny Pickles lent the Mill Company one of his men, Tommy Almond who was an expert firebeater. Tommy liked the job so well he stayed and in 1947 became engineer replacing Billy Lancaster. The Mill Company got a good man, Johnny lost one.

One more interesting thing about the engine. I have copies of indicator diagrams taken by the National Vulcan surveyor in May 1951 which show a vacuum of 26” water gauge. This is a good figure for an engine of this age. Newton loved the engine because in its later years, despite being the oldest engine in the district and very heavily loaded, in terms of coal burned and horse power delivered it was the most economical engine on Newton’s books. Not a bad record for an engine that ran for 107 years.

Victoria Mill, Earby in 1954, the broken fly shaft. Johnny Pickles is on the right and the man stood in front of him in the pin stripe suit is Teddy Woods from Procter and Procter at Burnley. I think the man behind Johnny is Tommy Almond who was engineer at the mill.

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 90298

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

CHAPTER 13: BOILERS AND BUTTS MILL

Butts mill in Barnoldswick has the distinction of being the first purpose-built steam driven mill in the town. It was erected by William ‘Billycock’ Bracewell in 1846 and was fully operational as a spinning and weaving mill in 1848.

I’m going to do it again, I feel a diversion coming on which will give us a good background and help us understand our subject. We need to know about boilers. Let’s take a step back and look at the boilers that were available in 1848. A local historian in Barlick, William Parkinson Atkinson, writing in about 1900 mentioned the boilers at Clough and Butts Mills in some detail. Here’s what he said, he is using the old term of ‘pan’ for the boilers: “Before going further, an explanation of the word ‘pan’ then in use, may be a little interesting and this will bring in also references to Butts as the two places, Clough and Butts, were in progress concurrently. (They were both being re-boilered at the time, 1862.) The ‘pan’ had no flues through it's centre, but was placed on a circular bed of brick-work which allowed a space of about eighteen inches or more between the bottom of the pan and the fire grate with a single oblong door in the centre, while the fire space would extend some three or four yards back from the door after which an aperture was allowed for the smoke before reaching the damper. The first two pans which came to Butts in 1848 were of this old style construction whilst those which came afterwards were of the modern type with two flues in each (now called) boiler. These were considered a great and economical improvement. Mr. William Bracewell had the two old pans taken out in the slack time and broken up about 186I. (This was during the Cotton Famine.) It was at this time, and while this work was being done that poor Jack Riding lost his life whilst superintending these operations. The boilers that came to Butts were made (by James Wardman) at Sandbeds near Keighley from thick iron plates and were much heavier than present day steel boilers, and when these old style boilers were brought by road and came to Gill Brow some thirty extra horses were required and caused quite a commotion round the town. At Clough Mill and New Shed (Referring to the new weaving shed at Clough) a new pan arrived, and a good bit of merriment was caused by the breaking of a rope whilst a lot of men and boys were helping to tug the pan from Low Gate(Walmsgate) across Peggy Field to the back of the mill. Nobody was hurt, and all seemed to enjoy the fun whilst they were laid prostrate on the ground.”

This is the account of a man who evidently witnessed what he described and I think we can trust the detail. It is reinforced in a diary for the year 1862 written by Richard Ryley who notes: “March 22nd. Went to meet the steam engine boiler which weighed fourteen and a half tons and the wagon on which it was brought weighed upwards of five tons more, altogether about twenty tons. It required twenty one horses and sixty or seventy men to drag it up Gill Brow.” It’s not certain whether this boiler was for Clough or Butts as both mills seem to have been supplied from Sandbeds .

One of the nice things about pursuing local history is that you have to range across the whole spectrum of the divisions historians create to make their subject manageable. In order to tell you the story we have to understand every aspect of it otherwise we arrive at situations where we haven’t enough knowledge to fully understand what’s going on. This is why I have to drag you sideways into what seem like diversions but are in fact essential guides to the content of the story.

I found myself in this position at one point when I was collating my research on the watermill at Lothersdale, near Cowling in the West Riding. There was a reference to the mill escaping the attention of the ‘plug drawers’ during the industrial unrest in the area in 1842 because it was in a remote valley. I knew that Bracewell’s Old Shed in Earby had been attacked and stopped by the same mob, presumably because it was more accessible but how much did I actually know about the Plug Riots? I decided to go forth to see what I could glean.