STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 90698

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

May 26th 1937. That a quotation from P D Bilborough dated May 18th 1937 for the supply of coal to both mills for 12 months to June 30th 1938 at 21/4 per ton for either Bentley washed singles or Airedale ditto, delivered at Barlick station less 1/2 per ton when delivered in our wagons be accepted.

June 16th 1937. Reported that a letter had been received re the tender for coal accepted at the previous meeting stating that the Coal Sales committee had refused to agree to it and that a revised tender would be necessary. Res. That the minute of the previous meeting be rescinded and that a contract be approved for the purchase of 1500 tons of Allerton Bywater washed singles at 23/4 per ton delivered at the station and for a supply of Bentley washed singles as required at 24/4 per ton delivered at the station. [The Coal Mines Act of 1930 introduced a system of quotas in the coal industry. Under the legislation companies were only allowed a certain market share in order to restrain competition. Local committees were set up in Lancashire which regulated prices and sources of supply but these were generally ineffective and were superseded by the later war measures (Emergency Powers (Defence) Act, 1939) under which the coal industry was controlled by central government who dictated prices and distribution policy. This was the end of private management of collieries until the Coal Mines Act of 1994 abolished the National Coal Board and led to privatisation of the 15 remaining pits.]

June 16th 1938. Coal contract. A tender for the supply of coal for 12 months from June 30th 1938 was received from P D Bilborough giving a price of 24/11 for Bentley coal and 24/4 for Airedale coal delivered at Barnoldswick station less 1/2 per ton for CH wagons. The contract for 1500 tons of Cortonwood at 24/4 expires on June 30th 1938. That the chairman and secretary settle the contracts for next year on the best terms possible.

July 21st 1938. That 1200 tons of Cortonwood coal at 25/7 per ton be purchased for the year ending June 30th 1939 and the balance required to be Bentley and Airedale at 24/11 and 24/4 respectively. [The Cortonwood contract may be directly with the colliery and not via a merchant.]

June 15th 1939. That the present coal contracts be continued for a further 12 months to June 30th 1940 at the present prices: Cortonwood 1200 tons at 25/7 per ton. Bentley 24/11 and Airedale 24/4.

May 23rd 1940. A letter from P D Bilborough was read re the coal contract, in which he quoted: Bentley washed singles at 27/5 per ton delivered to Barlick station. Airedale ditto 26/10. That the secretary confirm acceptance of the contract.

During the war no coal was purchased for the mills. It seems that one boiler was kept running for heating at Wellhouse fired with coke from the gasworks but this was not controlled by CHSC.

November 15th 1945. The secretary reported that a request had been made for an allocation of coal for Wellhouse Mill in place of coke but from the correspondence it seemed very doubtful that the application would be successful. [Coke was a by-product of the local gasworks and cut down on transport if it was used instead of coal.]

June 19th 1958. It was reported that considerable stocks of coal remained at Wellhouse Mill and it was agreed that deliveries be suspended for the time being. [Last entry on coal, shortly afterwards the engine was stopped.]

Coal must have been bought after 1945 but there is no mention in the minutes. The only evidence of coal costs is from the General Trading Accounts included with the balance sheets for the half yearly general meetings but we only have one: June 1945, £586. The payment of accounts in the minutes has no details so we are left in the dark. I think it's safe to assume that they pursued the same policy as pre-war, annual contracts with a merchant. Nationalisation made no difference to this mechanism as sale and distribution of coal was still done by established merchants acting for the National Coal Board. When I was running Bancroft in the 1970s the fuel was delivered by R Dennison and Son, a haulage contractor working for British Fuel which I think was a semi-official amalgamation of existing coal merchants.

It was a long haul from coal as low as 8/- a ton to modern prices via the amazing peak of almost 55/- during the General Strike. I'll leave it to the economists to produce an adjusted price based on real values, what interests me is what the directors had to cope with and their strategies.

June 16th 1937. Reported that a letter had been received re the tender for coal accepted at the previous meeting stating that the Coal Sales committee had refused to agree to it and that a revised tender would be necessary. Res. That the minute of the previous meeting be rescinded and that a contract be approved for the purchase of 1500 tons of Allerton Bywater washed singles at 23/4 per ton delivered at the station and for a supply of Bentley washed singles as required at 24/4 per ton delivered at the station. [The Coal Mines Act of 1930 introduced a system of quotas in the coal industry. Under the legislation companies were only allowed a certain market share in order to restrain competition. Local committees were set up in Lancashire which regulated prices and sources of supply but these were generally ineffective and were superseded by the later war measures (Emergency Powers (Defence) Act, 1939) under which the coal industry was controlled by central government who dictated prices and distribution policy. This was the end of private management of collieries until the Coal Mines Act of 1994 abolished the National Coal Board and led to privatisation of the 15 remaining pits.]

June 16th 1938. Coal contract. A tender for the supply of coal for 12 months from June 30th 1938 was received from P D Bilborough giving a price of 24/11 for Bentley coal and 24/4 for Airedale coal delivered at Barnoldswick station less 1/2 per ton for CH wagons. The contract for 1500 tons of Cortonwood at 24/4 expires on June 30th 1938. That the chairman and secretary settle the contracts for next year on the best terms possible.

July 21st 1938. That 1200 tons of Cortonwood coal at 25/7 per ton be purchased for the year ending June 30th 1939 and the balance required to be Bentley and Airedale at 24/11 and 24/4 respectively. [The Cortonwood contract may be directly with the colliery and not via a merchant.]

June 15th 1939. That the present coal contracts be continued for a further 12 months to June 30th 1940 at the present prices: Cortonwood 1200 tons at 25/7 per ton. Bentley 24/11 and Airedale 24/4.

May 23rd 1940. A letter from P D Bilborough was read re the coal contract, in which he quoted: Bentley washed singles at 27/5 per ton delivered to Barlick station. Airedale ditto 26/10. That the secretary confirm acceptance of the contract.

During the war no coal was purchased for the mills. It seems that one boiler was kept running for heating at Wellhouse fired with coke from the gasworks but this was not controlled by CHSC.

November 15th 1945. The secretary reported that a request had been made for an allocation of coal for Wellhouse Mill in place of coke but from the correspondence it seemed very doubtful that the application would be successful. [Coke was a by-product of the local gasworks and cut down on transport if it was used instead of coal.]

June 19th 1958. It was reported that considerable stocks of coal remained at Wellhouse Mill and it was agreed that deliveries be suspended for the time being. [Last entry on coal, shortly afterwards the engine was stopped.]

Coal must have been bought after 1945 but there is no mention in the minutes. The only evidence of coal costs is from the General Trading Accounts included with the balance sheets for the half yearly general meetings but we only have one: June 1945, £586. The payment of accounts in the minutes has no details so we are left in the dark. I think it's safe to assume that they pursued the same policy as pre-war, annual contracts with a merchant. Nationalisation made no difference to this mechanism as sale and distribution of coal was still done by established merchants acting for the National Coal Board. When I was running Bancroft in the 1970s the fuel was delivered by R Dennison and Son, a haulage contractor working for British Fuel which I think was a semi-official amalgamation of existing coal merchants.

It was a long haul from coal as low as 8/- a ton to modern prices via the amazing peak of almost 55/- during the General Strike. I'll leave it to the economists to produce an adjusted price based on real values, what interests me is what the directors had to cope with and their strategies.

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 90698

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

The first thing that strikes me is their first tentative moves into the coal market and the process of trial and error which led them to trusted suppliers and long term contracts. Along the way the most surprising entry is that of March 28th 1900 when they were considering buying a colliery, shades of William Bracewell and the Ingleton Collieries. I think that as far as they were concerned, the purchase of Silesian coal in June 1926 was probably quite astounding. The original minute referred to 'Sicilian' coal, it had taken the minute taker by surprise!

The overall problem they had was that coal was an international commodity. It's price and availability was governed by the export trade or lack of it after re-valuation of the currency. This in turn affected wage levels in the industry and cuts by the colliery owners led to the strikes which immediately had an effect on supply and price. Uncontrolled recruitment for the army in the early part of WW1 led to a labour shortage and had repercussions on supply. All these factors affected the running costs of the mills and rent levels. Coal price fluctuations were at first badly handled. True there was a coal clause in the rents but we have noted the problem which arose when the tenants thought the penalties of higher prices should be adjusted as soon as the price altered while the board were working on the price paid for the coal currently being burned which of course was a later date than the price change. One is reminded of the constant dichotomy today between world fuel prices and the cost to the consumer, the mechanism seems to be that the retail price rises with market price but lags behind any fall in the market. Reading between the lines, common sense prevailed and an accommodation was arrived at with the tenants.

Criticism based on hindsight is dangerous. Bearing this in mind it still surprises me that it took so long to recognise the benefit of long term contracts at an assured price as opposed to opportunistic cherry-picking of the market based on spot prices. There is a technical matter embedded in this thought. Firebeaters and engineers operated most efficiently with known fuels. The characteristics of coal vary from seam to seam and the strategies needed to burn them efficiently vary as well. We have a good example of this in the minute of April 18th 1917 where bad coal causes one firebeater to vote with his feet and his mate refuses weekend working. One of the consequences of bad coal is more frequent ashing-out which, apart from being a burden on the firebeater is grossly inefficient as regards fuel economy. Notice how, if an engine and boiler pant are hard pressed the board recognises this by giving them the best coal.

I have personal experience of this matter. During the miner’s strike in the 1970s I had to burn all the stock at Bancroft and when I got to the back of the stockpile I found some strange red rusty-looking stuff. It was some of the Lease-Lend brown coal which we imported from America after WW2 and I found out just how bad it was. On normal coal we ashed out twice a day, with this we were cleaning the fires every hour. When Newton Pickles had to burn this at Clough after the war he had to add old motor tyres to get it to burn!

Funnily enough a wagon turned up one day with a load of coal and instead of being the usual six-wheeler it was an eight-wheeler. We had a job getting him into the yard but managed and got him tipped. It was Sutton Manor washed singles from Lancashire, just about the best engine coal you could get and a big change from the rubbish we were burning. When I signed the driver's note I saw that the destination on it was not Bancroft but Bankfield, Rolls Royce. I didn’t say anything but just took the ticket up into the office and never heard anything more about it. I’ve often wondered who paid for that coal, it was lovely stuff and burned like candle ends so we used it with the red muck and it made the job a lot easier. I told Newton about it and we agreed that there must be a providence that looks after drunken men and firebeaters on bad coal.

One more peripheral matter. During my term as engineer at Bancroft I took fuel efficiency very seriously, read all I could on the subject and made significant improvements without major alterations to the plant. If you want to explore this further find my book on Bancroft Shed on Lulu.com, it's a complicated subject. What always struck me was that even in the 1970s the management never took fuel economy seriously, in fact, after I had reported on fuel economy one day the managing director told me that the only thing that would interest him would be when I sent coal back to the pit. The directors of CHSC were aware of these matters in later years and Teddy Wood in particular made significant improvements in the efficiency of the plant but I don't think they ever fully realised the scale of improvement that was possible. Another example of this from my own experience.

In 1978 I put a scheme up to the management at Bancroft whereby we could significantly improve fuel efficiency at no capital cost by burning the 300 tons of stock and using the savings on the coal account plus an available government grant to replace our old stokers with modern under-fired equipment. The result was that having realised the potential asset of burning the stock they told me to go ahead and as soon as it was gone they shut a profitable mill! (You're quite right, I may be biased.)

My point is that the technical blind spot I describe was, and I suspect still is, common. This despite the fact that during WW2 the government put a lot of effort into fuel efficiency, they had got the message. In 1944 the Ministry of Fuel and Power published 'The Efficient Use of Fuel' This was the first authoritative compendium of all the existing knowledge on the subject and it took a world war to initiate the work. My copy was bought by a man called Hilbert Burton, a mill owner in Brierfield, who had evidently seen the light. I allow myself the fantasy of how much money the board of the CHSC could have saved over the years if they had access to this knowledge. Ah well....

The bottom line of my enquiry into the CHSC and its use of coal is that despite all the perceived deficiencies visible with hindsight they paid a dividend almost every year. This was their goal and in those terms they did well.

The overall problem they had was that coal was an international commodity. It's price and availability was governed by the export trade or lack of it after re-valuation of the currency. This in turn affected wage levels in the industry and cuts by the colliery owners led to the strikes which immediately had an effect on supply and price. Uncontrolled recruitment for the army in the early part of WW1 led to a labour shortage and had repercussions on supply. All these factors affected the running costs of the mills and rent levels. Coal price fluctuations were at first badly handled. True there was a coal clause in the rents but we have noted the problem which arose when the tenants thought the penalties of higher prices should be adjusted as soon as the price altered while the board were working on the price paid for the coal currently being burned which of course was a later date than the price change. One is reminded of the constant dichotomy today between world fuel prices and the cost to the consumer, the mechanism seems to be that the retail price rises with market price but lags behind any fall in the market. Reading between the lines, common sense prevailed and an accommodation was arrived at with the tenants.

Criticism based on hindsight is dangerous. Bearing this in mind it still surprises me that it took so long to recognise the benefit of long term contracts at an assured price as opposed to opportunistic cherry-picking of the market based on spot prices. There is a technical matter embedded in this thought. Firebeaters and engineers operated most efficiently with known fuels. The characteristics of coal vary from seam to seam and the strategies needed to burn them efficiently vary as well. We have a good example of this in the minute of April 18th 1917 where bad coal causes one firebeater to vote with his feet and his mate refuses weekend working. One of the consequences of bad coal is more frequent ashing-out which, apart from being a burden on the firebeater is grossly inefficient as regards fuel economy. Notice how, if an engine and boiler pant are hard pressed the board recognises this by giving them the best coal.

I have personal experience of this matter. During the miner’s strike in the 1970s I had to burn all the stock at Bancroft and when I got to the back of the stockpile I found some strange red rusty-looking stuff. It was some of the Lease-Lend brown coal which we imported from America after WW2 and I found out just how bad it was. On normal coal we ashed out twice a day, with this we were cleaning the fires every hour. When Newton Pickles had to burn this at Clough after the war he had to add old motor tyres to get it to burn!

Funnily enough a wagon turned up one day with a load of coal and instead of being the usual six-wheeler it was an eight-wheeler. We had a job getting him into the yard but managed and got him tipped. It was Sutton Manor washed singles from Lancashire, just about the best engine coal you could get and a big change from the rubbish we were burning. When I signed the driver's note I saw that the destination on it was not Bancroft but Bankfield, Rolls Royce. I didn’t say anything but just took the ticket up into the office and never heard anything more about it. I’ve often wondered who paid for that coal, it was lovely stuff and burned like candle ends so we used it with the red muck and it made the job a lot easier. I told Newton about it and we agreed that there must be a providence that looks after drunken men and firebeaters on bad coal.

One more peripheral matter. During my term as engineer at Bancroft I took fuel efficiency very seriously, read all I could on the subject and made significant improvements without major alterations to the plant. If you want to explore this further find my book on Bancroft Shed on Lulu.com, it's a complicated subject. What always struck me was that even in the 1970s the management never took fuel economy seriously, in fact, after I had reported on fuel economy one day the managing director told me that the only thing that would interest him would be when I sent coal back to the pit. The directors of CHSC were aware of these matters in later years and Teddy Wood in particular made significant improvements in the efficiency of the plant but I don't think they ever fully realised the scale of improvement that was possible. Another example of this from my own experience.

In 1978 I put a scheme up to the management at Bancroft whereby we could significantly improve fuel efficiency at no capital cost by burning the 300 tons of stock and using the savings on the coal account plus an available government grant to replace our old stokers with modern under-fired equipment. The result was that having realised the potential asset of burning the stock they told me to go ahead and as soon as it was gone they shut a profitable mill! (You're quite right, I may be biased.)

My point is that the technical blind spot I describe was, and I suspect still is, common. This despite the fact that during WW2 the government put a lot of effort into fuel efficiency, they had got the message. In 1944 the Ministry of Fuel and Power published 'The Efficient Use of Fuel' This was the first authoritative compendium of all the existing knowledge on the subject and it took a world war to initiate the work. My copy was bought by a man called Hilbert Burton, a mill owner in Brierfield, who had evidently seen the light. I allow myself the fantasy of how much money the board of the CHSC could have saved over the years if they had access to this knowledge. Ah well....

The bottom line of my enquiry into the CHSC and its use of coal is that despite all the perceived deficiencies visible with hindsight they paid a dividend almost every year. This was their goal and in those terms they did well.

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

-

BillHowcroft

- Donor

- Posts: 102

- Joined: 19 Aug 2017, 17:39

- Location: Derby

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

I think I've still got a battered copy of The Efficient Use of Fuel in a box in the loft. In the mid-70s I was using it for steel-works energy efficiency studies. A lot of good British technical literature was triggered by the war whereas the Americans seemed to generate it during peacetime as well.

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 90698

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

I have a copy Bill and also 'The Efficient use of steam'. Still worth consulting, the basic physics hasn't changed!

CONCLUSIONS

There comes a point where research and interpretation has to stop. This always happens before you have finished extracting all the available evidence. There is so much more to be found by close examination of the balance sheets and financial performance. Much more could be done on the public perception of the shed companies, to a large extent they were shielded from negative feelings directed towards the 'rapacious' manufacturers as evidenced by the frequent strikes over wages, conditions and structural changes in management. However, anyone who researches Barlick in any depth will come across references to the 'Forty Thieves', a natural human reaction to the group of men who seemed to control the town and the shed company directors do not escape attention. I have evidence that an informal association of capital holders did exist and colluded to maximise their profits. Like any other human enterprise, the development of a town like Barlick is no random walk and contains the full spectrum from honest endeavour to cynical exploitation. The CHSC Minute Books are not a road map to this complex subject, they are a shaft of light on some important elements of the whole and individual readers will draw their own conclusions.

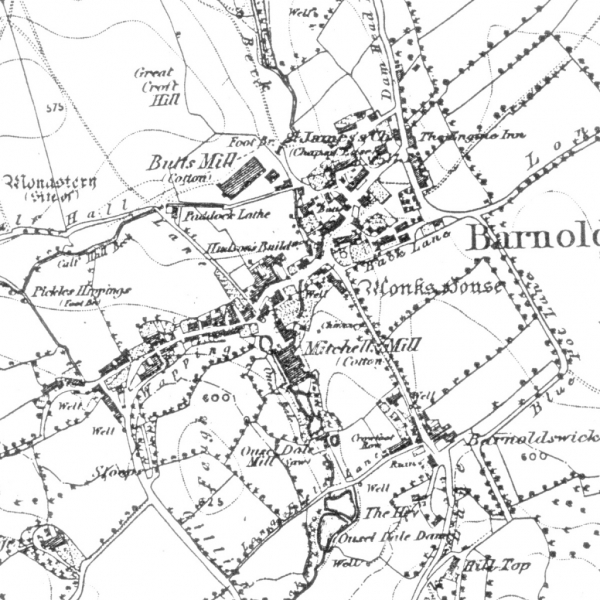

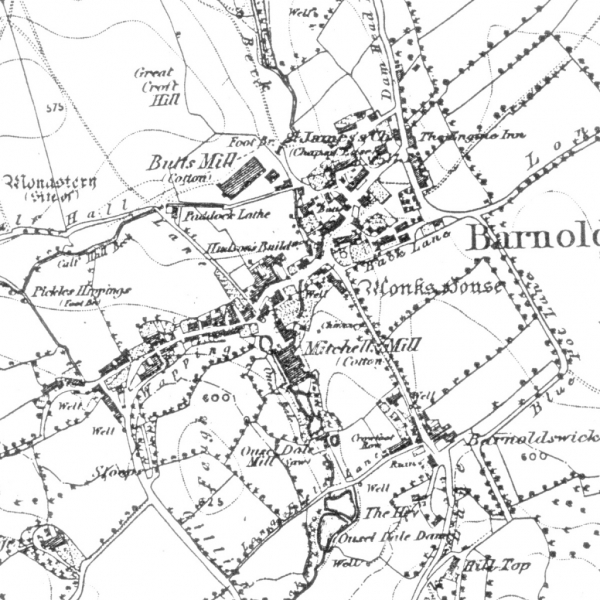

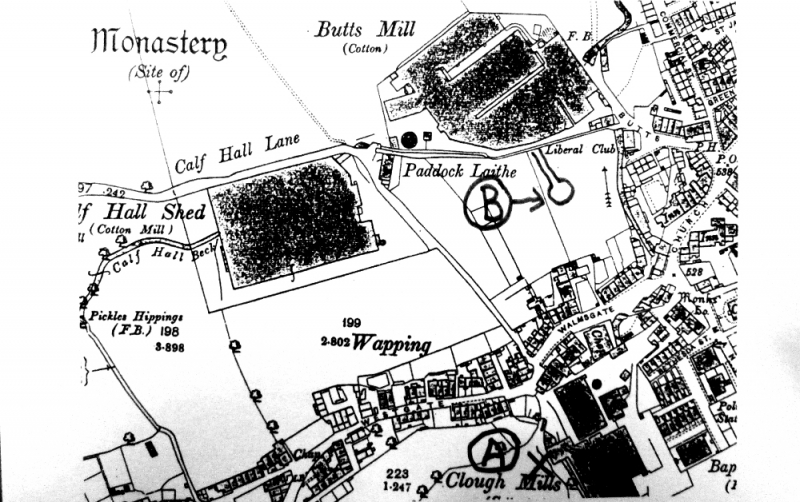

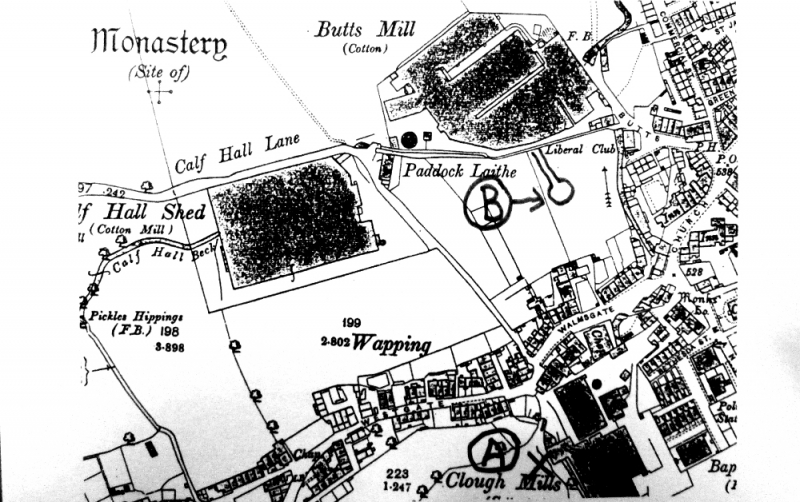

One thing we would do well to bear in mind is that what we have seen in Barlick didn't happen in a vacuum. We should always be aware of outside influence by national events. I have a kite to fly about this. I occasionally allow my mind to wander around the timing of Billycock's original incursion into Barlick to take advantage of what he evidently saw as an opportunity for expansion. Britain had one of its worst economic downturns in 1841/42. Butts Mill was under construction during the recovery of 1844/47 which saw a national boom in railway construction and an optimistic financial climate. There is a curious parallel in 1888 when the CHSC was promoted. There was a severe local crisis but nationally this was a time of peak profitability in the weaving trade. Timing is all and in this respect Bracewell and the CHSC might have much in common.

I have to admit to a sneaking regard for the promoters of the company. On the one hand they are a classic example of 19th century laissez faire capitalism but on the other, they were a group of public minded entrepreneurs who saw a problem, a possible solution and a way to go forward. I don't think anyone can immerse themselves in the story without getting a definite impression that one of their aims was the betterment of the town. Granted, this had implications for them, their status and personal fortunes but at no point do I detect that this was the over-riding goal. Look at the tone of the speeches reported from the christening ceremony at Calf Hall in 1889. Brooks Banks, the chairman said “He would rather take 100 sheep with little wool than one blustering tup with it all.” I'm sure he was making a reference to the dead hand of the Bracewell hegemony and putting himself, the directors and their enterprise firmly in the anti-Bracewell camp. Even a commentator as deferential as William Parkinson Atkinson alluded to the “big dog and little dog” problems. I talked to Stephen Pickles, son of the Stephen Pickles in the minutes, and he confirmed that my feeling that Bracewell and Sons had a bad press was correct. What we don't get from the minutes is that in 1866 the Pickles family gave up on Barlick and moved en masse to New England on the promise of three acres and a cow. They soon realised their mistake and came back but the memory of the failure of the town's industry to support budding entrepreneurs remained strong down the generations. In the end of course, the small manufacturers produced the giants of the Barlick trade and some like the Pickles family outlasted the rest of the industry. The last weaving shed in Barlick was Holden's 90 looms at Wellhouse.

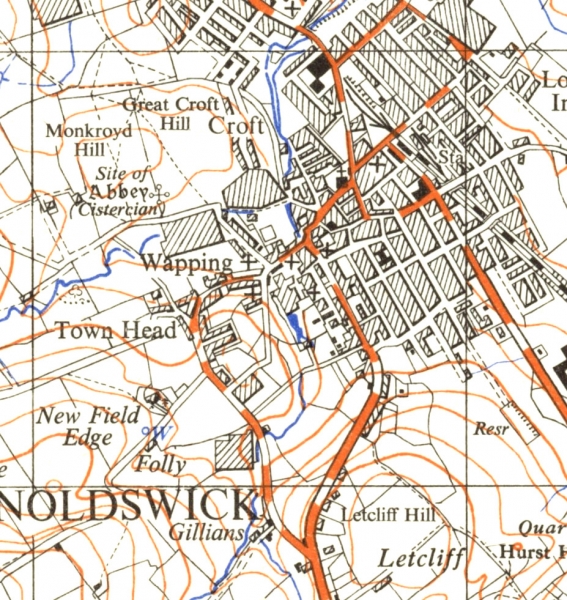

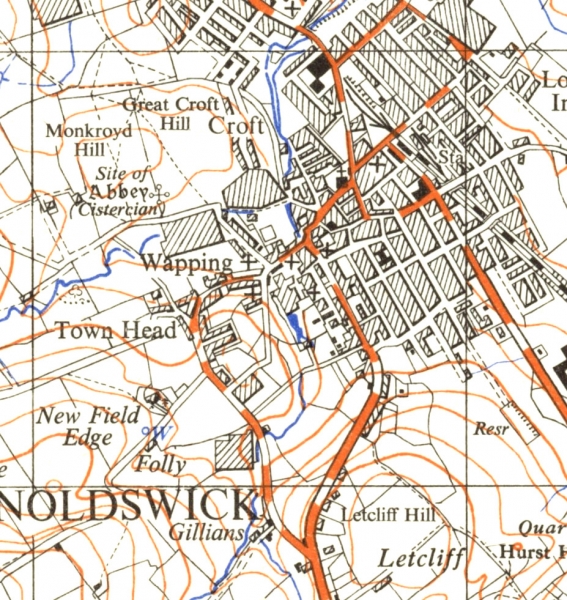

One of my main objectives in publicising the minutes and writing this book was to put some flesh on the bones of what is known generally about the shed companies and their operations. You will be the judge of whether I have added anything to the research. As for the advent of the shed companies in Barlick, we can have no doubt that in at least one respect, the CHSC promoters triumphed completely. The growth of Barlick from 1890 to 1914 is a direct consequence of the impetus given to manufacturing by the low threshold of entry into the trade by room and power provided by the shed companies. The names of the promoters of the new mills built in the town are synonymous with the early tenants in the Long Ing and Calf Hall companies. The additional investment which financed the new builds after 1900 came from the retail trades who had done well out of the general expansion. Barnsey Shed built in 1911 had two nicknames, one was 'Bouncer' and the other was 'Pots and Pans', the latter because one of the major shareholders was Sam Yates the tinsmith from Church Street, his wife christened the HP cylinder. There is only one manufacturer amongst the first directors at Barnsey, all the others were from retail trade and service industries. Economists often cite the 'trickle down effect' of investment in key industries. Nowhere is this more true than in Barlick.

It doesn't end there. House building and population exploded alongside the mills. It was the attraction of the family wage and equal pay under the piecework system that drove inward migration to the mill towns. Many families with children working in the mills had very substantial incomes particularly if the father was one of the working class aristocracy, a taper, tackler or winding master. These families built houses to rent, often with a shop attached to provide employment for the wife. This was seen as provision for old age in the days when the fear of the workhouse was still very real. The consequence was that from 1914 until the council house building post 1945, apart from a few houses built as infill, there was no new housing needed in the town. Visitors to the town, especially from the US often comment that almost every building would be a Landmark building at home.

Despite the vicissitudes of occasional downturns in trade the workers, on the whole, prospered. There was enough money in the town to support three cinemas, at one time a roller skating rink, three orchestras and even, in the middle of the inter war depression, a country club at Bracewell Hall. The basis of this growth in the culture of Barlick was the solid bedrock of money that came out of the mills at all levels. The legacy of well built stone houses serves us to this day, these were not archetypal slums, but sound properties. I live in one myself and wouldn't dream of swapping it for a new house even if I could afford it.

We must take note of one last legacy of the expansion triggered by room and power in the shed companies. This was the availability of large empty mills in 1939 which allowed the Shadow Factories to be located here. After the war these modernised premises attracted the new industries which are still with us today and gave us the Rolls Royce works. Without this sequence of events it's difficult to see what Barlick's course from the death of weaving into the modern world would have been. By an accident of fate the government was forced to inject investment into the town and it's salutary to note that our greatest benefactor was probably Adolph Hitler. There's an unlikely combination for you, the shed companies and an evil dictator. Time to put up a monument? I occasionally wonder what the effect would have been on the inter-war depression if the same principles of rational reorganisation and public investment had been applied to industry still locked into 19th century laissez faire principles.

CONCLUSIONS

There comes a point where research and interpretation has to stop. This always happens before you have finished extracting all the available evidence. There is so much more to be found by close examination of the balance sheets and financial performance. Much more could be done on the public perception of the shed companies, to a large extent they were shielded from negative feelings directed towards the 'rapacious' manufacturers as evidenced by the frequent strikes over wages, conditions and structural changes in management. However, anyone who researches Barlick in any depth will come across references to the 'Forty Thieves', a natural human reaction to the group of men who seemed to control the town and the shed company directors do not escape attention. I have evidence that an informal association of capital holders did exist and colluded to maximise their profits. Like any other human enterprise, the development of a town like Barlick is no random walk and contains the full spectrum from honest endeavour to cynical exploitation. The CHSC Minute Books are not a road map to this complex subject, they are a shaft of light on some important elements of the whole and individual readers will draw their own conclusions.

One thing we would do well to bear in mind is that what we have seen in Barlick didn't happen in a vacuum. We should always be aware of outside influence by national events. I have a kite to fly about this. I occasionally allow my mind to wander around the timing of Billycock's original incursion into Barlick to take advantage of what he evidently saw as an opportunity for expansion. Britain had one of its worst economic downturns in 1841/42. Butts Mill was under construction during the recovery of 1844/47 which saw a national boom in railway construction and an optimistic financial climate. There is a curious parallel in 1888 when the CHSC was promoted. There was a severe local crisis but nationally this was a time of peak profitability in the weaving trade. Timing is all and in this respect Bracewell and the CHSC might have much in common.

I have to admit to a sneaking regard for the promoters of the company. On the one hand they are a classic example of 19th century laissez faire capitalism but on the other, they were a group of public minded entrepreneurs who saw a problem, a possible solution and a way to go forward. I don't think anyone can immerse themselves in the story without getting a definite impression that one of their aims was the betterment of the town. Granted, this had implications for them, their status and personal fortunes but at no point do I detect that this was the over-riding goal. Look at the tone of the speeches reported from the christening ceremony at Calf Hall in 1889. Brooks Banks, the chairman said “He would rather take 100 sheep with little wool than one blustering tup with it all.” I'm sure he was making a reference to the dead hand of the Bracewell hegemony and putting himself, the directors and their enterprise firmly in the anti-Bracewell camp. Even a commentator as deferential as William Parkinson Atkinson alluded to the “big dog and little dog” problems. I talked to Stephen Pickles, son of the Stephen Pickles in the minutes, and he confirmed that my feeling that Bracewell and Sons had a bad press was correct. What we don't get from the minutes is that in 1866 the Pickles family gave up on Barlick and moved en masse to New England on the promise of three acres and a cow. They soon realised their mistake and came back but the memory of the failure of the town's industry to support budding entrepreneurs remained strong down the generations. In the end of course, the small manufacturers produced the giants of the Barlick trade and some like the Pickles family outlasted the rest of the industry. The last weaving shed in Barlick was Holden's 90 looms at Wellhouse.

One of my main objectives in publicising the minutes and writing this book was to put some flesh on the bones of what is known generally about the shed companies and their operations. You will be the judge of whether I have added anything to the research. As for the advent of the shed companies in Barlick, we can have no doubt that in at least one respect, the CHSC promoters triumphed completely. The growth of Barlick from 1890 to 1914 is a direct consequence of the impetus given to manufacturing by the low threshold of entry into the trade by room and power provided by the shed companies. The names of the promoters of the new mills built in the town are synonymous with the early tenants in the Long Ing and Calf Hall companies. The additional investment which financed the new builds after 1900 came from the retail trades who had done well out of the general expansion. Barnsey Shed built in 1911 had two nicknames, one was 'Bouncer' and the other was 'Pots and Pans', the latter because one of the major shareholders was Sam Yates the tinsmith from Church Street, his wife christened the HP cylinder. There is only one manufacturer amongst the first directors at Barnsey, all the others were from retail trade and service industries. Economists often cite the 'trickle down effect' of investment in key industries. Nowhere is this more true than in Barlick.

It doesn't end there. House building and population exploded alongside the mills. It was the attraction of the family wage and equal pay under the piecework system that drove inward migration to the mill towns. Many families with children working in the mills had very substantial incomes particularly if the father was one of the working class aristocracy, a taper, tackler or winding master. These families built houses to rent, often with a shop attached to provide employment for the wife. This was seen as provision for old age in the days when the fear of the workhouse was still very real. The consequence was that from 1914 until the council house building post 1945, apart from a few houses built as infill, there was no new housing needed in the town. Visitors to the town, especially from the US often comment that almost every building would be a Landmark building at home.

Despite the vicissitudes of occasional downturns in trade the workers, on the whole, prospered. There was enough money in the town to support three cinemas, at one time a roller skating rink, three orchestras and even, in the middle of the inter war depression, a country club at Bracewell Hall. The basis of this growth in the culture of Barlick was the solid bedrock of money that came out of the mills at all levels. The legacy of well built stone houses serves us to this day, these were not archetypal slums, but sound properties. I live in one myself and wouldn't dream of swapping it for a new house even if I could afford it.

We must take note of one last legacy of the expansion triggered by room and power in the shed companies. This was the availability of large empty mills in 1939 which allowed the Shadow Factories to be located here. After the war these modernised premises attracted the new industries which are still with us today and gave us the Rolls Royce works. Without this sequence of events it's difficult to see what Barlick's course from the death of weaving into the modern world would have been. By an accident of fate the government was forced to inject investment into the town and it's salutary to note that our greatest benefactor was probably Adolph Hitler. There's an unlikely combination for you, the shed companies and an evil dictator. Time to put up a monument? I occasionally wonder what the effect would have been on the inter-war depression if the same principles of rational reorganisation and public investment had been applied to industry still locked into 19th century laissez faire principles.

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 90698

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

So, what's my conclusion? The concept of the shed company which built mills specifically to cater for the small manufacturers while never entering the trade themselves was efficient and enlightened. Efficient because it gave a low threshold of entry and freedom to specialise. Enlightened because the aim was to increase employment and nurture profitable enterprises. They were a natural successor to the concept of partners renting space in the old water-powered mills and it's noticeable that the only firm which prohibited this sharing of opportunity, the Bracewells, was the one which failed. The verdict must be that they were a complete success.

I'll leave you with that thought, a recommendation and a story. Seek out one of my favourite books, Harold Macmillan's 'Middle Way' published in 1938. The story is that one day in 1979 I happened to be on King's Cross station and had occasion to ask the passenger in a car that was causing an obstruction if he could move. I tapped on the rear window and when it was wound down I found myself face to face with our Harold! I was so taken aback the only thing that came out of my mouth was “I've read the Middle Way”. He smiled and said “I wish others would do the same!” My point is that the man seen by many as a right wing reactionary advocated public ownership, government investment in key industries and a middle way between 19th century laissez faire Capitalism and rampant Socialism.

Couldn't resist that. Incidentally, I recently found a quotation attributed to Harold less than a month before he died in 1986. He had seen the figure for unemployment in his old constituency of Stockton on Tees which was 28%, just one percentage point lower than when he was MP from 1924-1929. He said it was “A rather sad end to one's life”.

APPENDICES

These two documents are not directly CHSC related but they put some flesh on the bones of the effects of WW2 on the manufacturers in Barlick and give an idea of the human scale behind the impersonal data embedded in the number of looms. 625 workers in a 1000 loom unit. These are human beings working to feed families and fill bottom drawers ready for a wedding. We do well to remember them.

One example; we can calculate from the Bancroft list an average of four and a half looms per worker. Looking at the totals for looms in 1941 and 1947 we can make the educated estimate that 2,970 workers ran the Barlick looms in 1941 and only 1640 in 1947. A loss of 1,330 jobs.

LICENSED LOOMS IN BARLICK WW2

In the 1930s the government, as part of the measures to correct problems in the textile industry, formed a statutory body called The Cotton Control Board. One of the board's strategies was to make a census of all looms in use and during WW2 they brought in a licensing scheme whereby they could control the number of looms operating and where they were situated. This meant that some mills were forced to go out of production and many redundant looms were stored all over the town in the expectation that the end of the war would bring a revival in the trade.

Like many of these initiatives, we know they existed but have very little reliable local evidence. Luckily, when Bancroft Shed was being demolished I managed to save some papers from the office and one of these was a little gem, the pre-war census figures for looms in the town and a list made by year of those running during the war.

It would be too complicated to give the complete figures but here are enough of them to give an idea of how the manufacturers fared under licensing which came into effect after April 1941.

NUMBER OF LOOMS OPERATING

FIRM March 1940 Nov. 1941 Oct 1947

S Pickles and Son 432 nil nil

Craven Man. Co Ltd 1260 nil nil

Butts Man. Co Ltd 420 nil nil

New Road Man. Co Ltd 432 nil nil

S Pickles and Sons Ltd nil 1680 1722

B&EM Holden Ltd 432 282 240

M Horsfield and Sons Ltd 414 151 163

Cairns and Lang Ltd 635 524 335

Robinson Brooks Ltd 987 731 730

James Nutter Ltd 1183 1152 945

Horsfield (B'field) Ltd 321 120 109

Proctor&Co (Barlick) Ltd 420 250 250

WE&D Nutter Ltd 1125 nil nil

John Widdup & Sons Ltd 1116 700 650

Alderton Bros Ltd 432 293 293

T S Edmondson 432 nil nil

Nutter Bros Ltd 1192 406 325

James Slater Ltd 638 nil 302

H Ellison Ltd 50 88 99

Ellerbank Man Co Ltd 118 110 110

Manock Gill and Co Ltd 660 520 550

Edmondson (F'bank) Ltd 660 520 550

Totals. 13359 7529 7373

In November 1941 the licence fee per loom per annum was 1/3. From February 1942 until the end of licensing in 1947 it was 1/6 per loom per annum.

LIST OF WORKERS AT BANCROFT SHED ON

DECEMBER 5th 1941

Name address occupation age

W E Nutter The Knoll Man. Director 59

F W Mattocks Gisburn Road Salesman

Vernon Nutter 25 Park Road Manager 42

W Bracewell 44 Lower Rook St Clerk 17

Fred Midgley 1 Calf Hall Rd Engineer

Harry Brown 2 Mosley St Fireman 27

W W Wilson 12 Rainhall Rd Motor driver

R Sharples 28 Park Ave Cloth looker 37

J T Isherwood 18 Back Park St Cloth looker 41

George Nutter 61 Park Rd Cloth looker 61

Jn. Greenhalgh 12 Skipton Rd Cloth looker

Walter Naylor 3 Robert St Cloth looker 33

Thomas Roper 12 Frank Street Warehouseman 54

Harold Parker 12 North Parade Warehouseman 46

Cyrus Eccleston 45 Wellington St Night watchman

Fred Naylor 3 Robert St Night watchman 58

John Burrell 42 Rosemont Ave Tape labourer 30

Joe Calverly Taylor Avenue Taper

Rennie Shepherd 28 Victoria Rd Taper 50

W K Whiteoak 146 Gisburn Rd Machine operator 30

Wm Eccleston 15 Beech Grove Machine operator 55

Robert Walker 16 Cavendish St Loomer 46

D Brennand 10 Taylor St Loomer 67

Lawrence Kieron 4 Hollins Rd Loomer charge hand 39

Wm Tomlinson 48 Manchester Rd Head overlooker 38

J Carr 24 Beech Street overlooker

L Steele 2 Essie Terrace Overlooker

Les Beaumont 26 Cobden St Overlooker 51

Richard Lord 17 Sackville St Overlooker 46

Edward Burke 9 Powell St Overlooker 49

Eddie Green 53 Harrison St Overlooker

George Stretch 11 Alice St Weaver 51

Alfred Geldard 7 Bethel St Weaver 57

Sam Ottie 35 York St Weaver 62

Bracewell Stanley 15 James St Weaver 61

Cyril Brown 5 Pleasant View Weaver 38

Clifford Hartley 33 Gisburn St Weaver 41

J W Wellock 23 Bruce St Weaver 63

Arthur Stockdale 6 Park Road Weaver 48

Edward Pickup 8 Essie Terrace Weaver 44

Rennie Brown 34 Park Avenue Weaver

Tom Harrison 37 Lower East Ave Weaver 40

Holbury Metcalfe 19 Clarence St Weaver 62

Sam Wiseman 9 Montrose Terrace Weaver 42

Fred Pearson 27 Beech St Weaver 42

Wm Coppinge 58 M/c Road Weaver 51

Thos Lawson 62 Uppr York St Weaver 41

Clarence Downs 50 Park St Weaver 54

Robert Beckett 6 Gillians Weaver 39

Joe Croasdale 2 Lane Bottoms Weaver 62

Fred Brown Willow Bank M/c Rd Weaver 36

Herbert Brown 4 Rook Street Weaver 52

Alan Preston 8 Cavendish St Weaver 32

Wilfred Preston 19 Earl St Weaver 38

Luther Duxbury 11 Park Street Weaver 45

Craven Waddington 21 Park Rd Weaver 48

Edward Fishwick 74 York St Weaver 53

John Tattersall 47 Park Rd Weaver 50

Harry Cawdrey 10 Cavendish St Weaver 49

Thos Horrocks 13 Colne Rd Weaver 62

J W Dent 17 Turner St Weaver 36

Sid Myers 21 East Hill St Weaver 30

Wm Shuttleworth 4 Rook Street Weaver 54

Jn C Taylor 7 Clifford Street Weaver 58

Walter Smalley Lynfield Tubber Hill Weaver 61

Fred Exley Lynfield Tubber Hill Weaver 49

Rennie Geldard 18 Butts Weaver 44

Harry Moody 55 Lower Park St Weaver 48

Alfred Thomas 5 Lane Bottom Weaver 41

Joe Bentley 59 Cobden Street Weaver 50

Ron Tattersall 47 Park Rd Weaver 18

Les Wilson 19 Colne Road Weaver 16

Thomas Green 9 Town Head Weaver

Chas Watson 71 Lower Rook St Weaver 70

Jim Unsworth 50 Esp Lane Weaver

Henry Preston 8 Cavendish St Weaver 67

James Waygood 6a Hartley St Weaver 68

Thos Taylor 4 Park Street Weaver 65

John Wilson 17 James Street Weaver 66

H Edmondson 60 Skipton Road Weaver 69

Fred Barrett Standridge Farm Weaver 66

Jim Robinson 3 Ribblesdale Ter Weaver 68

Joe Brooksbank 23 Essex St Weaver 65

Wm. Metcalfe Burdock Hill Weaver 72

Rich. Pollard 3 Bank House Flats Weaver 69

K Harwood Twister 16

L Golding 40 Park Road Weaver 33

Henry Brown 28 Valley Road Weaver 54

James Monk 152 M/c Road Loomer

Alice Stell 11 Sackville St Weaver 61

Mrs Schofield 4 Fountain Street Weaver

J Hodgkinson 20 Bracewell St Beamer

M Davy 42 Lower Rook St Winder

M MacDonald 53 Esp Lane Weaver 60

Mary Horrocks 13 Colne Road Weaver 62

Rose Mason 69 Sunset View Weaver 64

Anne MacDonald Winder

Ethel Hartley Weaver 41

Ivy Robinson Weaver 44

Margaret Stretch Weaver 50

Ellen Pate Weaver 19

Evelyn Conboy

Winnie Bennett Weaver 29

Alice Hartley Weaver 42

Hilda Pickering Weaver

Annie Metcalfe Weaver 35

Florrie Geldard Weaver 52

Jessie Pearson Weaver 39

Clarice Moore Weaver 38

Marion Chadwick Weaver 38

Nellie Duxbury Weaver

Bessie Tomlinson Weaver 32

Mary Calverly Weaver 49

Eva Smith Weaver 31

Eliz. Boothman Weaver 36

Ellen Waddington Weaver 29

Ruby Swire Weaver

Mary Sharples Weaver 30

Kath Kiernan Weaver

Dorothy Cawdrey Weaver 48

Hilda Brown Weaver

Gertrude Coppinge Weaver 49

Minnie Wiseman Weaver 55

Nellie Clarke Weaver

Millie Broughton Weaver 29

Alice Sharples Weaver 50

Mary Ashley Weaver 54

Maud Chadwick Weaver 52

Violet Bailey Weaver 45

Edith Edmondson Weaver 43

Nellie Demaine Weaver 42

Doris Brennand Weaver 25

Mary Duckworth Weaver 46

Mabel Pearson Weaver 46

Mona Platt Weaver 30

Gladys Aldersley Weaver 24

Evelyn Ratcliffe Weaver 42

Mary Stockdale Weaver 49

Elsie Pearson Weaver 37

Chrissie Eccleston Weaver 21

Kate Lord Weaver 42

Anne Cope Weaver 49

May Robinson Weaver 53

Marion Turner Weaver 25

Louise Green Weaver 35

Phyllis Parkinson Weaver 31

Edith Brown Weaver 33

Eliza Mason Weaver 55

Chrissie Plumbley Weaver 43

Winnie Parkinson Weaver 26

Mabel Lodge Weaver 52

Ruth Hacking Weaver 41

Lilly Taylor Weaver 52

Jessie Smith Weaver 32

Eva Pateman Weaver 39

Gladys Newbould Weaver 50

Mary Dacre Weaver 50

Alice Cryer Weaver 39

Gwen Moore Weaver 40

Laura Demaine Weaver

Emily Gorton Weaver 39

Polly Fishwick Weaver 53

Eliza Daly Weaver 45

Eliza Chatwood Weaver 28

Elsie Pickering Weaver 47

Doris Stockdale Weaver 40

Daisy Kenyon Weaver

Jane Nutter Weaver 49

Hilda Bailey Weaver 33

Mary Monks Weaver 47

Ethel Holden Weaver 42

Elsie Mason Weaver 34

Annie Burke Weaver 47

Mary O’Neill Weaver 19

Nellie Moore Weaver

Olive Moore Weaver 38

Anne Astin Weaver 39

Maud Reid Weaver 48

Gertrude Gleeson Weaver 42

Elsie Hargreaves Weaver 40

Jennie Waterworth Weaver 24

Winnie Bentley Weaver 46

Annie Exley Weaver 43

Edith Lawson Weaver 38

Emily Waterworth Weaver 35

Evelyn Lee Weaver 34

Eliz. Hayes Weaver

Florence Crerar Weaver 54

Polly Hodson Weaver 33

Mary Downs Weaver 28

Annie Bell Weaver 37

Jane Craddock Weaver 32

Annie Stephens Weaver 24

Nora Titherington Weaver 21

Eva Nutter Weaver 31

Gladys Dobson Weaver 34

Sarah Edmondson Weaver 53

Mary Holt Weaver

Alice Demaine Weaver 32

Sarah Bracewell Weaver 26

Muriel Daly Winder

Lillian Whiteoak Winder

Alice Martin Weaver 40

Elsie Windle Weaver 26

Dorothy Hesketh Winder

Mrs Moss Winder

L Palmer Winder

H Clarke Winder

May Brooks Weaver 40

Ethel Ashworth Weaver 51

Annie Green Weaver 40

Ivy Pickup Weaver 33

Olga Hartley Weaver 19

Ida Brennand Weaver 20

Joan Cope Weaver 19

Doris King Weaver 20

Jean Holmes Weaver 18

Hilda Green Weaver 18

Nora Heyes Weaver 19

Madge Edmondson Weaver 16

Olive Reid Weaver 16

Eliz. Demaine Weaver 17

Greta Holmes Weaver 15

Enid Holden Weaver 16

Nellie Hudson Weaver 24

[Transcribed by Stanley Challenger Graham from the original return made by the management at Bancroft Shed. 225 workers in total, 1000 looms reported as licensed in February 1942. average of four and a half looms per worker.]

I'll leave you with that thought, a recommendation and a story. Seek out one of my favourite books, Harold Macmillan's 'Middle Way' published in 1938. The story is that one day in 1979 I happened to be on King's Cross station and had occasion to ask the passenger in a car that was causing an obstruction if he could move. I tapped on the rear window and when it was wound down I found myself face to face with our Harold! I was so taken aback the only thing that came out of my mouth was “I've read the Middle Way”. He smiled and said “I wish others would do the same!” My point is that the man seen by many as a right wing reactionary advocated public ownership, government investment in key industries and a middle way between 19th century laissez faire Capitalism and rampant Socialism.

Couldn't resist that. Incidentally, I recently found a quotation attributed to Harold less than a month before he died in 1986. He had seen the figure for unemployment in his old constituency of Stockton on Tees which was 28%, just one percentage point lower than when he was MP from 1924-1929. He said it was “A rather sad end to one's life”.

APPENDICES

These two documents are not directly CHSC related but they put some flesh on the bones of the effects of WW2 on the manufacturers in Barlick and give an idea of the human scale behind the impersonal data embedded in the number of looms. 625 workers in a 1000 loom unit. These are human beings working to feed families and fill bottom drawers ready for a wedding. We do well to remember them.

One example; we can calculate from the Bancroft list an average of four and a half looms per worker. Looking at the totals for looms in 1941 and 1947 we can make the educated estimate that 2,970 workers ran the Barlick looms in 1941 and only 1640 in 1947. A loss of 1,330 jobs.

LICENSED LOOMS IN BARLICK WW2

In the 1930s the government, as part of the measures to correct problems in the textile industry, formed a statutory body called The Cotton Control Board. One of the board's strategies was to make a census of all looms in use and during WW2 they brought in a licensing scheme whereby they could control the number of looms operating and where they were situated. This meant that some mills were forced to go out of production and many redundant looms were stored all over the town in the expectation that the end of the war would bring a revival in the trade.

Like many of these initiatives, we know they existed but have very little reliable local evidence. Luckily, when Bancroft Shed was being demolished I managed to save some papers from the office and one of these was a little gem, the pre-war census figures for looms in the town and a list made by year of those running during the war.

It would be too complicated to give the complete figures but here are enough of them to give an idea of how the manufacturers fared under licensing which came into effect after April 1941.

NUMBER OF LOOMS OPERATING

FIRM March 1940 Nov. 1941 Oct 1947

S Pickles and Son 432 nil nil

Craven Man. Co Ltd 1260 nil nil

Butts Man. Co Ltd 420 nil nil

New Road Man. Co Ltd 432 nil nil

S Pickles and Sons Ltd nil 1680 1722

B&EM Holden Ltd 432 282 240

M Horsfield and Sons Ltd 414 151 163

Cairns and Lang Ltd 635 524 335

Robinson Brooks Ltd 987 731 730

James Nutter Ltd 1183 1152 945

Horsfield (B'field) Ltd 321 120 109

Proctor&Co (Barlick) Ltd 420 250 250

WE&D Nutter Ltd 1125 nil nil

John Widdup & Sons Ltd 1116 700 650

Alderton Bros Ltd 432 293 293

T S Edmondson 432 nil nil

Nutter Bros Ltd 1192 406 325

James Slater Ltd 638 nil 302

H Ellison Ltd 50 88 99

Ellerbank Man Co Ltd 118 110 110

Manock Gill and Co Ltd 660 520 550

Edmondson (F'bank) Ltd 660 520 550

Totals. 13359 7529 7373

In November 1941 the licence fee per loom per annum was 1/3. From February 1942 until the end of licensing in 1947 it was 1/6 per loom per annum.

LIST OF WORKERS AT BANCROFT SHED ON

DECEMBER 5th 1941

Name address occupation age

W E Nutter The Knoll Man. Director 59

F W Mattocks Gisburn Road Salesman

Vernon Nutter 25 Park Road Manager 42

W Bracewell 44 Lower Rook St Clerk 17

Fred Midgley 1 Calf Hall Rd Engineer

Harry Brown 2 Mosley St Fireman 27

W W Wilson 12 Rainhall Rd Motor driver

R Sharples 28 Park Ave Cloth looker 37

J T Isherwood 18 Back Park St Cloth looker 41

George Nutter 61 Park Rd Cloth looker 61

Jn. Greenhalgh 12 Skipton Rd Cloth looker

Walter Naylor 3 Robert St Cloth looker 33

Thomas Roper 12 Frank Street Warehouseman 54

Harold Parker 12 North Parade Warehouseman 46

Cyrus Eccleston 45 Wellington St Night watchman

Fred Naylor 3 Robert St Night watchman 58

John Burrell 42 Rosemont Ave Tape labourer 30

Joe Calverly Taylor Avenue Taper

Rennie Shepherd 28 Victoria Rd Taper 50

W K Whiteoak 146 Gisburn Rd Machine operator 30

Wm Eccleston 15 Beech Grove Machine operator 55

Robert Walker 16 Cavendish St Loomer 46

D Brennand 10 Taylor St Loomer 67

Lawrence Kieron 4 Hollins Rd Loomer charge hand 39

Wm Tomlinson 48 Manchester Rd Head overlooker 38

J Carr 24 Beech Street overlooker

L Steele 2 Essie Terrace Overlooker

Les Beaumont 26 Cobden St Overlooker 51

Richard Lord 17 Sackville St Overlooker 46

Edward Burke 9 Powell St Overlooker 49

Eddie Green 53 Harrison St Overlooker

George Stretch 11 Alice St Weaver 51

Alfred Geldard 7 Bethel St Weaver 57

Sam Ottie 35 York St Weaver 62

Bracewell Stanley 15 James St Weaver 61

Cyril Brown 5 Pleasant View Weaver 38

Clifford Hartley 33 Gisburn St Weaver 41

J W Wellock 23 Bruce St Weaver 63

Arthur Stockdale 6 Park Road Weaver 48

Edward Pickup 8 Essie Terrace Weaver 44

Rennie Brown 34 Park Avenue Weaver

Tom Harrison 37 Lower East Ave Weaver 40

Holbury Metcalfe 19 Clarence St Weaver 62

Sam Wiseman 9 Montrose Terrace Weaver 42

Fred Pearson 27 Beech St Weaver 42

Wm Coppinge 58 M/c Road Weaver 51

Thos Lawson 62 Uppr York St Weaver 41

Clarence Downs 50 Park St Weaver 54

Robert Beckett 6 Gillians Weaver 39

Joe Croasdale 2 Lane Bottoms Weaver 62

Fred Brown Willow Bank M/c Rd Weaver 36

Herbert Brown 4 Rook Street Weaver 52

Alan Preston 8 Cavendish St Weaver 32

Wilfred Preston 19 Earl St Weaver 38

Luther Duxbury 11 Park Street Weaver 45

Craven Waddington 21 Park Rd Weaver 48

Edward Fishwick 74 York St Weaver 53

John Tattersall 47 Park Rd Weaver 50

Harry Cawdrey 10 Cavendish St Weaver 49

Thos Horrocks 13 Colne Rd Weaver 62

J W Dent 17 Turner St Weaver 36

Sid Myers 21 East Hill St Weaver 30

Wm Shuttleworth 4 Rook Street Weaver 54

Jn C Taylor 7 Clifford Street Weaver 58

Walter Smalley Lynfield Tubber Hill Weaver 61

Fred Exley Lynfield Tubber Hill Weaver 49

Rennie Geldard 18 Butts Weaver 44

Harry Moody 55 Lower Park St Weaver 48

Alfred Thomas 5 Lane Bottom Weaver 41

Joe Bentley 59 Cobden Street Weaver 50

Ron Tattersall 47 Park Rd Weaver 18

Les Wilson 19 Colne Road Weaver 16

Thomas Green 9 Town Head Weaver

Chas Watson 71 Lower Rook St Weaver 70

Jim Unsworth 50 Esp Lane Weaver

Henry Preston 8 Cavendish St Weaver 67

James Waygood 6a Hartley St Weaver 68

Thos Taylor 4 Park Street Weaver 65

John Wilson 17 James Street Weaver 66

H Edmondson 60 Skipton Road Weaver 69

Fred Barrett Standridge Farm Weaver 66

Jim Robinson 3 Ribblesdale Ter Weaver 68

Joe Brooksbank 23 Essex St Weaver 65

Wm. Metcalfe Burdock Hill Weaver 72

Rich. Pollard 3 Bank House Flats Weaver 69

K Harwood Twister 16

L Golding 40 Park Road Weaver 33

Henry Brown 28 Valley Road Weaver 54

James Monk 152 M/c Road Loomer

Alice Stell 11 Sackville St Weaver 61

Mrs Schofield 4 Fountain Street Weaver

J Hodgkinson 20 Bracewell St Beamer

M Davy 42 Lower Rook St Winder

M MacDonald 53 Esp Lane Weaver 60

Mary Horrocks 13 Colne Road Weaver 62

Rose Mason 69 Sunset View Weaver 64

Anne MacDonald Winder

Ethel Hartley Weaver 41

Ivy Robinson Weaver 44

Margaret Stretch Weaver 50

Ellen Pate Weaver 19

Evelyn Conboy

Winnie Bennett Weaver 29

Alice Hartley Weaver 42

Hilda Pickering Weaver

Annie Metcalfe Weaver 35

Florrie Geldard Weaver 52

Jessie Pearson Weaver 39

Clarice Moore Weaver 38

Marion Chadwick Weaver 38

Nellie Duxbury Weaver

Bessie Tomlinson Weaver 32

Mary Calverly Weaver 49

Eva Smith Weaver 31

Eliz. Boothman Weaver 36

Ellen Waddington Weaver 29

Ruby Swire Weaver

Mary Sharples Weaver 30

Kath Kiernan Weaver

Dorothy Cawdrey Weaver 48

Hilda Brown Weaver

Gertrude Coppinge Weaver 49

Minnie Wiseman Weaver 55

Nellie Clarke Weaver

Millie Broughton Weaver 29

Alice Sharples Weaver 50

Mary Ashley Weaver 54

Maud Chadwick Weaver 52

Violet Bailey Weaver 45

Edith Edmondson Weaver 43

Nellie Demaine Weaver 42

Doris Brennand Weaver 25

Mary Duckworth Weaver 46

Mabel Pearson Weaver 46

Mona Platt Weaver 30

Gladys Aldersley Weaver 24

Evelyn Ratcliffe Weaver 42

Mary Stockdale Weaver 49

Elsie Pearson Weaver 37

Chrissie Eccleston Weaver 21

Kate Lord Weaver 42

Anne Cope Weaver 49

May Robinson Weaver 53

Marion Turner Weaver 25

Louise Green Weaver 35

Phyllis Parkinson Weaver 31

Edith Brown Weaver 33

Eliza Mason Weaver 55

Chrissie Plumbley Weaver 43

Winnie Parkinson Weaver 26

Mabel Lodge Weaver 52

Ruth Hacking Weaver 41

Lilly Taylor Weaver 52

Jessie Smith Weaver 32

Eva Pateman Weaver 39

Gladys Newbould Weaver 50

Mary Dacre Weaver 50

Alice Cryer Weaver 39

Gwen Moore Weaver 40

Laura Demaine Weaver

Emily Gorton Weaver 39

Polly Fishwick Weaver 53

Eliza Daly Weaver 45

Eliza Chatwood Weaver 28

Elsie Pickering Weaver 47

Doris Stockdale Weaver 40

Daisy Kenyon Weaver

Jane Nutter Weaver 49

Hilda Bailey Weaver 33

Mary Monks Weaver 47

Ethel Holden Weaver 42

Elsie Mason Weaver 34

Annie Burke Weaver 47

Mary O’Neill Weaver 19

Nellie Moore Weaver

Olive Moore Weaver 38

Anne Astin Weaver 39

Maud Reid Weaver 48

Gertrude Gleeson Weaver 42

Elsie Hargreaves Weaver 40

Jennie Waterworth Weaver 24

Winnie Bentley Weaver 46

Annie Exley Weaver 43

Edith Lawson Weaver 38

Emily Waterworth Weaver 35

Evelyn Lee Weaver 34

Eliz. Hayes Weaver

Florence Crerar Weaver 54

Polly Hodson Weaver 33

Mary Downs Weaver 28

Annie Bell Weaver 37

Jane Craddock Weaver 32

Annie Stephens Weaver 24

Nora Titherington Weaver 21

Eva Nutter Weaver 31

Gladys Dobson Weaver 34

Sarah Edmondson Weaver 53

Mary Holt Weaver

Alice Demaine Weaver 32

Sarah Bracewell Weaver 26

Muriel Daly Winder

Lillian Whiteoak Winder

Alice Martin Weaver 40

Elsie Windle Weaver 26

Dorothy Hesketh Winder

Mrs Moss Winder

L Palmer Winder

H Clarke Winder

May Brooks Weaver 40

Ethel Ashworth Weaver 51

Annie Green Weaver 40

Ivy Pickup Weaver 33

Olga Hartley Weaver 19

Ida Brennand Weaver 20

Joan Cope Weaver 19

Doris King Weaver 20

Jean Holmes Weaver 18

Hilda Green Weaver 18

Nora Heyes Weaver 19

Madge Edmondson Weaver 16

Olive Reid Weaver 16

Eliz. Demaine Weaver 17

Greta Holmes Weaver 15

Enid Holden Weaver 16

Nellie Hudson Weaver 24

[Transcribed by Stanley Challenger Graham from the original return made by the management at Bancroft Shed. 225 workers in total, 1000 looms reported as licensed in February 1942. average of four and a half looms per worker.]

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 90698

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

BRACEWELL V BRACEWELL SMITH AND THRELFALL

Transcription of an article in the Nelson Times, Saturday June 9th 1888.

A BARNOLDSWICK CHANCERY SUIT.

Bracewell versus Bracewell, Smith and Threlfall.

On Tuesday [5th June 1888] the case of Bracewell versus Bracewell, Smith and Threlfall came up for hearing in the Chancery Division of the Royal Courts of Justice Keckawich. Sir Charles Russell, QC, MP and Mr O L Clare appeared for the Plaintiff, Mrs Elizabeth Bracewell. Mr Bigham QC and Mr Samuel Hall and Mr Farewell were for the Defendant Mr C G Bracewell and Mr Neville QC, MP and Mr Swinfen Eady appeared for the Defendants Smith and Threlfall.

Sir Charles Russell, in opening the case, said it was an action to recover certain sums of money, about £21,000 odd, from the defendants in respect of her late husband’s share in the business of William Bracewell and Sons. The Plaintiff was the widow of the late William Metcalfe Bracewell who was a partner in the firm of William Bracewell and Sons, Cotton Spinners, Manufacturers and Corn Millers of Barnoldswick and Burnley. About September 1879 a partnership was entered into between William Bracewell, the father, and William Metcalfe Bracewell and Christopher George Bracewell his sons, but no written articles of Partnership were ever executed. It was however verbally agreed that the business and assets should belong to the partners in the proportion of five-tenths to Mr William Bracewell, three-tenths to Mr William Metcalfe Bracewell and two-tenths to Christopher George Bracewell and the partnership was carried on on that footing until 10th of June 1880. He [William Metcalfe] died intestate leaving a widow (the present plaintiff) and three children. His widow took out Letters of Administration to his estate. In May of the following year the amount of capital of Mr William Metcalfe Bracewell’s share was ascertained to be £19,509-9-8 and that amount was entered in the books of the firm to the credit of an account named ‘William Metcalfe Bracewell’s estate in account with William Bracewell and Sons’ . Then the Plaintiff applied to the firm for payment of her share and threatened proceedings against them for the recovery of it. However it was ultimately agreed to that if the Plaintiff would not press the firm for immediate payment Mr William Bracewell personally guaranteeing the payment of the amount with interest at the rate of £3 per cent per annum until paid, and on the 6th of July 1882, four promissory notes payable on demand for £4,335-8-10, £4,335-8-10, £4,335-8-10 and £6,503-3-3 respectively were signed by him and given to the Plaintiff as collateral security for the sum of £19,509-9-8 the amount of her late husband’s share in the business. [Making the total capital of the partnership £65,000] Mr William Bracewell made his will on the 1st of March 1885 and appointed the defendants executors and trustees of his real estate. On the 13th of the same month he died and his will was duly proved by the defendants. Various sums had from time to time been paid by the firm before and since the death of Mr William Bracewell in respect of his deceased son’s shares but all those sums had been insufficient to keep down the accruing interest and over £21,000 was due and owing to the plaintiff from the firm. Since the death of Mr William Bracewell, the plaintiff had repeatedly applied to Mr Christopher George Bracewell as surviving partner and to the defendants Mr Smith Smith and Mr Joseph Henry Threlfall as executors for payment of the above amount. She had also demanded payment of the promissory notes but her demands had not been complied with. Since the death of his father, Mr Christopher Bracewell had continued to carry on the business alone. On 9th April 1886 an action was commenced in the Chancery of the County Palatine of Lancaster by Christopher George Bracewell against Smith Smith and Joseph Henry Threlfall and also Mrs Mary Jane Bracewell (two of the beneficiaries under the will of William Bracewell) for the administration of the trusts of the will and on the 28th of July 1886 an order was made for the trusts of the will and various accounts and enquiries were directed together with a reference to Chambers, to appoint a Receiver. In conclusion the learned council said in point of law he did not think there could be very much controversy or matter for controversy between them. When Mr William Metcalfe Bracewell died it could not be doubted that the firm was liable to his representatives for his interest in the firm, and the interest was fixed by Mr William Bracewell, as he would show by the evidence of Mr Matthew Watson, at the figure of £19,509-9-8. He submitted that the onus was on the defendants to show that this lady, who represented her own interests and the interests of her infant children, had done something which operated as a release of the liability of Christopher George Bracewell.

MRS ELIZABETH BRACEWELL examined by Sir Charles Russell said that she was sent for by her father-in-law in May 1882, in consequence of a letter which Mr Hodgson, her solicitor, had sent to him relative to the money due to her in respect of her husband’s share in the business. He showed her the letter and asked if she had authorised Mr Hodgson to write it. He was in a great rage and offered to give the whole thing up and told her to take it into her own hands and manage the best way she could. She was leaving the office and he called her back and asked her to get ready to go with Mr Eastwood, the book-keeper to Burnley, and they by the next train went to see Mr Matthew Watson with respect to this matter. Mr Bracewell said he was as much responsible for the children’s interest as she was, but she objected to that. It was not so and she was solely interested. She was not present when the promissory notes were signed. She saw Mr Bracewell the following evening and he said she had asked for nothing that was not right, and added that he had made ‘All square’. He would give her the notes. He said he had given her a double surety on his private estate as well as upon the Partnership and said she might have them made up in shares for the children and one for herself and then if she required she could be paid out. Between the time of her husband’s death and the time when she received the promissory notes Mr William Bracewell sent her £5 a week for household expenses.

Cross-examined by Mr Bigham she said that Mr Bracewell advised her to go to Mr Watson.--- Mr Bigham: Do you mean to say that after you got these promissory notes you believed that nobody but your father-in-law was liable to you in respect of this money? Just let me read it to you: ‘I promise to pay on demand to Elizabeth Bracewell on her order the sum of £6,503-3-3, being part of the sum of £19,509-9-9 due from me to my late son William Metcalfe Bracewell on the day of his death which occurred on the 10th of June 1880 the said sum of £6,503-3-3 to bear interest after the rate of five per cent per annum payable half-yearly.’ Did you read it when you got it? The Witness: ‘Yes’ --- Do you mean to tell my Lord that after these negotiations with the father you regarded the firm, or Christopher George Bracewell, who was not the monied man, as in any way liable to you in respect of the money which your husband had left in the firm? ‘Yes, I always considered the firm responsible.’

In reply to Mr Neville the witness said that she claimed the promissory notes as security for what was due to her husband from the firm of William Bracewell and Sons, and also from the separate estate of William Bracewell.

MR MATTHEW WATSON, auctioneer of Burnley said he examined the books of Bracewell and Sons and found that William Metcalfe Bracewell’s share in the concern was three-tenths. No stock was taken at the time the partnership was entered into. He saw Mr Bracewell Senior on the Manchester Exchange and spoke to him about giving security to Mrs Bracewell. He was very indignant and said that all he could do was make his private property available as well as the partnership and he was willing to give the promissory notes as collateral security, and the whole business was carried out along those lines. He (the witness) never heard of such a thing as Mr Bracewell buying his late son’s interest in the firm. He asked for an account to see how matters stood and he received one on the 9th of December 1881. He found £19,599-9-8[sic] due to William Metcalfe Bracewell at the time of his death.

Cross examined he said he was first called in for the purpose of ascertaining the value of the personal estate for administration purposes. He examined the ledger. The ledger was only posted up to the year 1878.

In reply to Mr Neville he said the sum of £22,816-5-6 included £10,000 which the late William Metcalfe Bracewell paid into partnership.

Mr James Hodgson was called and said he acted as solicitor for the Plaintiff. She instructed him to write the letter referred to, to Mr Bracewell, demanding security.

This concluded the case for the Plaintiff.

Mr Bigham, on behalf of the defendant Bracewell pointed out that even on the case presented to the court by the Plaintiff, it was perfectly obvious that an account must be taken. His Lordship agreed with that and observed that he could not say anything which would justify him in holding that there was an account stated binding Christopher George Bracewell.

Mr Justice Keckawich, in giving judgement said that his opinion on the matter of law was that in order to fix the amount due to the estate of a deceased partner from the surviving partners, both those surviving partners must concur in taking the account though one of them might depute the duty to the other. In this case there was no sufficient evidence to make it a right conclusion that Mr William Bracewell, though the senior partner, and holding by far the largest share, and being apparently of a despotic disposition, had authority to bind Christopher George Bracewell, the junior partner. That being his decision however, he hoped the parties would have the good sense to come to some understanding as to what amount they ought to part with because, there having been no stocktaking at the commencement of the partnership and there having been no stocktaking at the death of Mr William Bracewell, but the whole thing as being between relations was conducted in a somewhat loose manner, the expense of taking the account would be very great and would not fall unfortunately on one party alone. Mr C G Bracewell would suffer and Mrs Elizabeth Bracewell would suffer. After some discussion his Lordship directed an account to be taken.

[Transcribed by SCG, 28 January 2004 from a photocopy given to him by Geoff Shackleton.]

Transcription of an article in the Nelson Times, Saturday June 9th 1888.

A BARNOLDSWICK CHANCERY SUIT.

Bracewell versus Bracewell, Smith and Threlfall.

On Tuesday [5th June 1888] the case of Bracewell versus Bracewell, Smith and Threlfall came up for hearing in the Chancery Division of the Royal Courts of Justice Keckawich. Sir Charles Russell, QC, MP and Mr O L Clare appeared for the Plaintiff, Mrs Elizabeth Bracewell. Mr Bigham QC and Mr Samuel Hall and Mr Farewell were for the Defendant Mr C G Bracewell and Mr Neville QC, MP and Mr Swinfen Eady appeared for the Defendants Smith and Threlfall.