I asked Newton about County Brook. This is a very old water mill on the County Brook at OS reference SD887439. It started as a corn mill but then became a forerunner of a modern chemical works because they started to burn charcoal in enclosed retorts so that they could collect and condense the smoke coming off the wood. This was known as ‘stewing wood’ and produced all sorts of fractions from what is known as Stockholm Tar to phenols and other chemicals. The chief thing they were after were chemicals that could be used as a mordant in the dyeing trade, a chemical used to fix the dye in the cloth. This is why many people still call it the Stew Mill. In the mid nineteenth century a man called Mitchell bought it and converted it into a water-powered cotton mill against all the latest trends but was successful, so much so that it is still weaving in 2009 and owned by the Mitchell family. Here’s what Newton had to say.

“Well, County Brook was a very old mill. When I was a lad the bit that was left of the old mill and the water wheel was still running. The wheel ran on to a shaft that ran to another shaft and there was a sixty horse power National Diesel coupled to it and the diesel engine governed the water wheel. (The classic method of getting a regular turning speed from water power.) They reckoned they used to get about forty horse out of the water wheel when they had water but when the water was done the engine had to turn the water wheel as well, they couldn’t knock it out of gear because there were no clutch. (Not as big a disadvantage as it sounds because there would always be some water coming over the wheel even if the flow was greatly reduced.) Then they extended that shed and we did the millwrighting for it, and they put another two hundred looms in. We did all that millwrighting and pulled the old oil engine out and National brought a new one (1938). They went from sixty horse power to a hundred horse National Engine, slow running and not totally enclosed. They run at about 130revs a minute, a big fine engine. We put a new line shaft in, all new pulleys and then we put a 60 hp electric motor in as well just in case trade were bad and they could run just one shed with the motor, or if there were no water they could start the motor up. They were all on fast and loose pulleys were the shaft drive from the motor, about seven feet long with an eight inch belt on about an inch thick. They’d a real set up up there. Then we extended the place again after a few years for another two hundred looms and a two storey building to form a cellar underneath. We did all that job but that ran separately with an electric motor at the top of the steps just where you went up into the shed. One big motor, about a hundred horse.

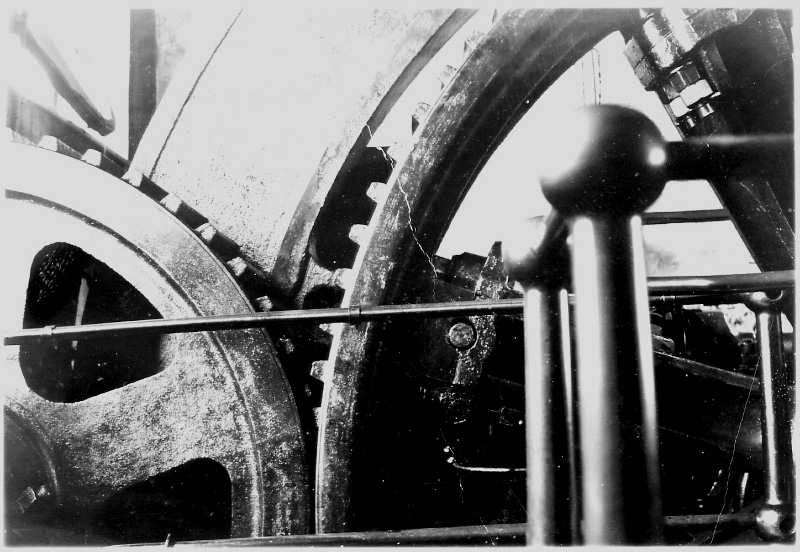

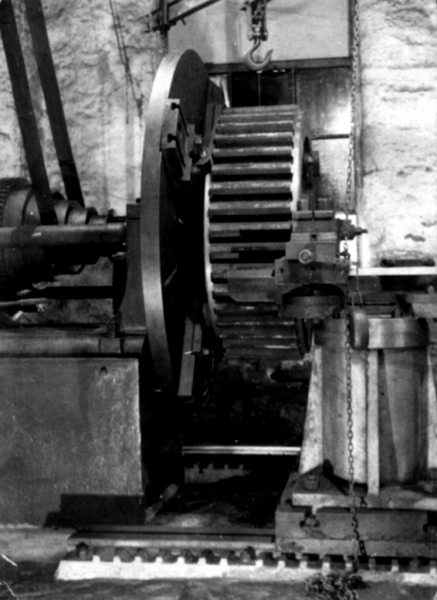

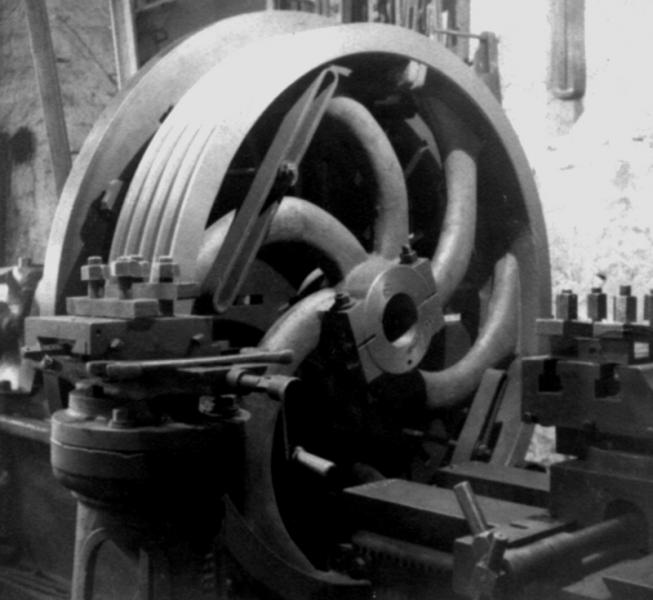

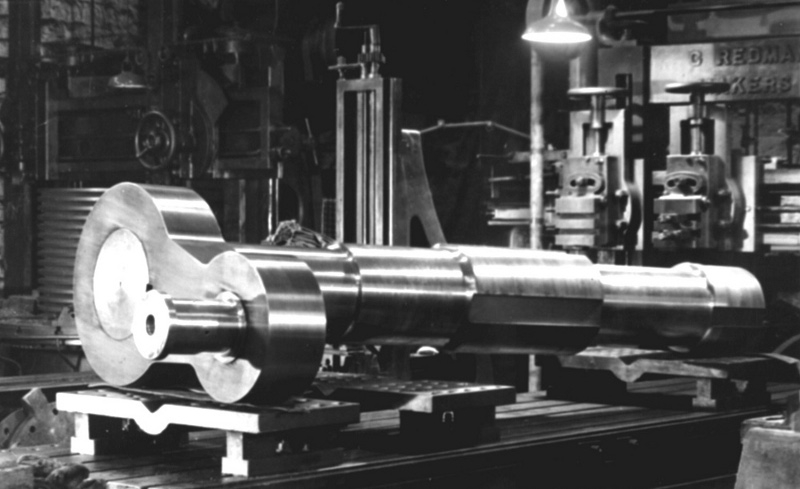

The water wheel were a wood construction wheel with a cast iron shaft and wooden spokes right up to the wheel segments and steel buckets which must have been renewed many times which we repaired once or twice. Cast iron segments, by segments I mean in the form of a gear wheel round the outer edge. It’d be about twenty five feet in diameter and six feet wide. The segments were getting worn, if one broke we’d go and put a new segment in. And the pinion, you couldn’t lubricate it with cylinder oil and ordinary grease. (Because it washed off, the pinion was showered with water when the wheel was running.) What they used to lubricate the segments with on that were gas tar, road gas tar, they found that was the most efficient lubrication you could put on a water wheel.

Then it started acting up, it were allus wearing teeth out in the pinion and the pinion ‘ud be about four feet in diameter. I think the teeth were about three inches pitch, you didn’t get many teeth in a four feet diameter wheel at that pitch you know. It used to wear ‘em out pretty regularly and we’d go and put a new one on. I said it’s running queer is this wheel one day to me father. He says what’s up with it Newton? Well I said, it’s reight in gear at one side but its out of gear at the other side. He said you’ll have to lift the shaft up at one end and lower it at t’other to make it line up. I said, well, if I lift it that much it’ll be through the roof! Oh, he said, like that is it. So we went and had a look, popped a level on t’water wheel shaft while it were stopped one Saturday morning and t’bubble went out of sight in’t level like. So we had a reight look at it and found that gear side bearing had worn reight down, they were running on cast iron pedestals you know, it had worn right down through the pedestal on to the stone. (It wasn’t unusual in the early technology to use a cast iron bearing surface for a wrought iron shaft. They run well together. The same applies to steel running in cast iron or steel running on Lignum Vitae, a vary hard tropical wood, if it’s under water. The step bearing at the bottom of a vertical water turbine was always a Lignum Vitae ball and they would run for years with no lubrication but water. The same wood was used for the stern gland in early steam ships to seal the shaft against water leaking in.) So Mitchell (the owner) says well, you’ll have to do sommat with that, we’re not doing without the water wheel. So me father gets his wood rule out and takes particulars, makes a pattern to make a new bearing but this time we put a bronze step in it didn’t we. And a hell of a thing it was and all, because I remember me and Bob Fort carrying that bronze step from t’shop up to County Brook. The wagon were out so me father says oh, take it on the bus. There weren’t a bus so we walked all the way, he’d carry it a few yards and then I’d carry it a few to the top of, where you live, reight to the top of Tubber Hill and then there’s a gate and you go down through the field. I think we slid it down through the field on the snow or sommat. Anyhow, that’s nowt, we get this bearing in. And to hold that water wheel up, it were a bigger job than lifting any mill engine flywheel. There’s no room, we made two holes in the wall through each side of the spokes you know. We put two girders in, about ten by six and bolted ‘em together. Then we put some straps across and we made some inch and a half bolts and straps under the shaft and we tightened them to lift the wheel up. You couldn’t put jacks under it, you’d nothing only two straight walls. We pulled it up like that to get it clear of the bearings and the shaft I think was worn about two inch of taper on the shaft end! It’d been running for years like that hadn’t it? So me father says well, we can’t make a bearing that’ll fit that shaft so he got it cast on the same taper, we didn’t machine it and me and Bob took it up and that’s how we were going to deal with it, offer it up, bring it back, do a little bit at it and try to make it fit better. So anyhow we just dropped the wheel down on to this new bearing and it looked beautiful and straight, in fact it were leaning the other way! So before we put the pinion on we decided the time had come to run the wheel without the pinion on for a bit to see how the bearing went on. When we come to lower the wheel the penstock had been leaking and the buckets were all full on the drive side and as we were lowering it down it were trying to go round. It started to bend them ruddy bolts and by the time we’d got those bolts out they were just like, well they’d have made a good bow and arrow out of the four you know they’d bent that much curve on them. Anyhow we got it to drop down on to this bearing and we got it running.

We only put a drop of water on to get it spinning round, we’d no gearing on you know and it could go! Believe it or believe it not water went all over the place and you couldn’t get anywhere near it, you wanted a sou’wester on and a mac like a fisherman. That bearing got red hot and it smoked and it sizzled with all that water running on it, it did that. So we shut the water off and got it stopped and I went down to the shop and me father says well, how’s it going on? I said How’s it going on? I’ve never had a hot neck on a water wheel before! He says what! I says we’ve a bloody hot neck Johnny on that water wheel. Never he says, I can’t believe that. Bob says you go up and have a look Johnny, there’s steam coming off it! He he he! And you can’t get near it for water! I must see this he says, I must see this! So I got some Victory Compound which is red moulding sand of course, nicely dried. He says are you going to put that on it Newton? Well I said, I can’t think of anything else! So off we went back with this big box of Victory Compound. Johnny stood well back, while we put the water on and got it going. I bet within ten seconds the bugger were smoking. Whoa! he says, and water were squirting all over the place, get some Victory mixed! I said mix it be buggered let’s put it on raw! So we put this sand on the shaft, no oil in it or nowt, and it ground and it screamed and it squeaked. By gum, in ten minutes it were a perfect fit and it never ailed another thing. It ran right up to them pulling it out and putting a turbine in. They used to get forty horse power out of that water wheel, I mean free, as long as Whitemoor reservoir was running over, you know.”

The old water wheel shaft is still on display at County Brook. If you look carefully you can see how badly roped the journals are. Looking at the shaft in 2018 I realised that I made a mistake in the text when I suggested it was wrought iron. This is quite obviously a cast iron shaft and it's a miracle it survived all those years, they often broke in very cold weather when the metal was brittle.

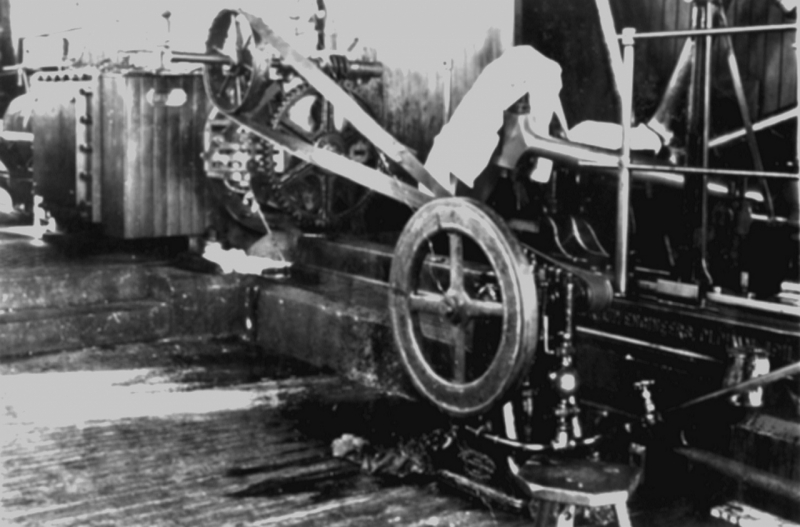

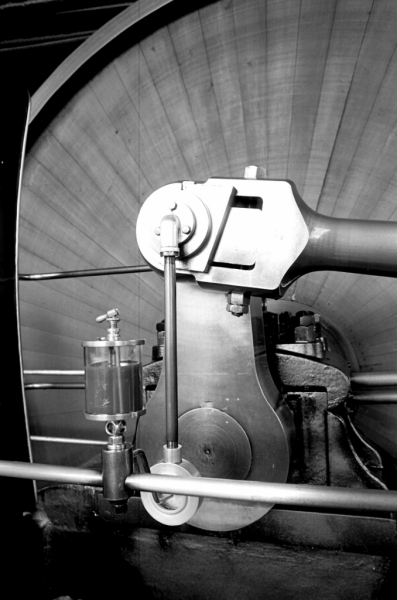

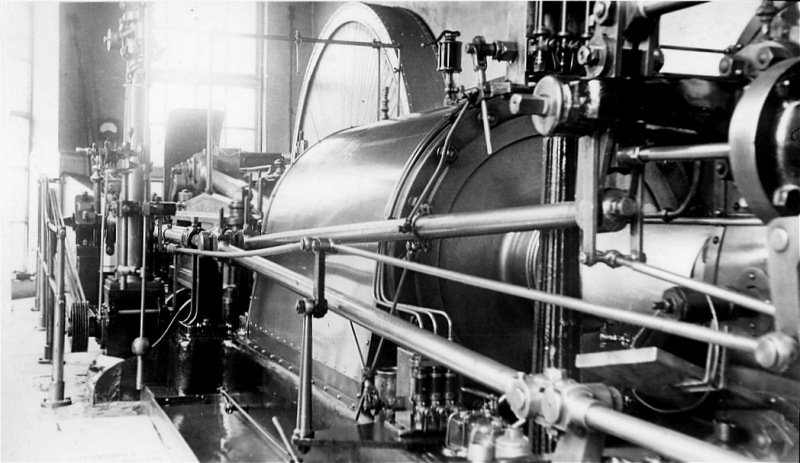

The County Brook wheel was very similar to this one at the fulling mill in Helmshore.