Anyone who has followed the fortunes of the textile industry will be well aware of the simplistic arguments that have been advanced over the years to explain why the fall from supremacy to oblivion was so abrupt and complete. It’s worth noting that in terms of production and sales, the national consumption of cotton cloth is higher now than at any time during the peak of the industry. The global figures are even more striking. So, ignoring short term fluctuations in the market which are always with us and to a certain extent predictable, there is no simple answer on the demand side. An economist once made the simple observation that it was ridiculous to suppose that Britain should ever try to become a banana producer, all right this is so obvious as to be a given. I was once asked by a school teacher where the last cotton fields were in England. Think about these two sentences, there is a clue embedded in them.

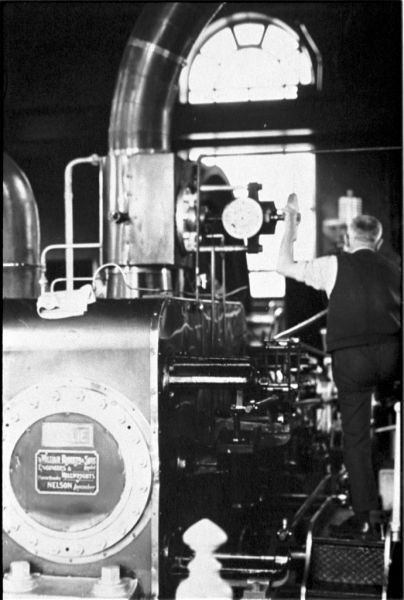

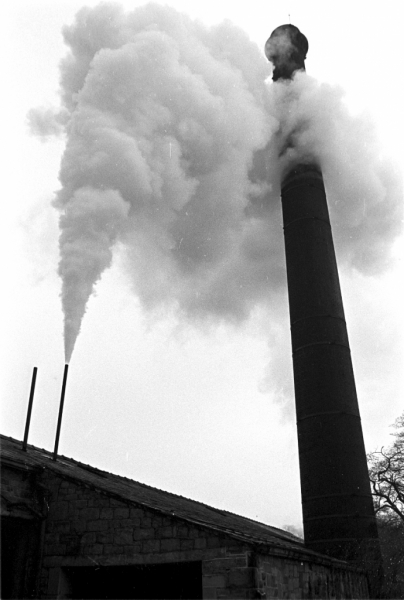

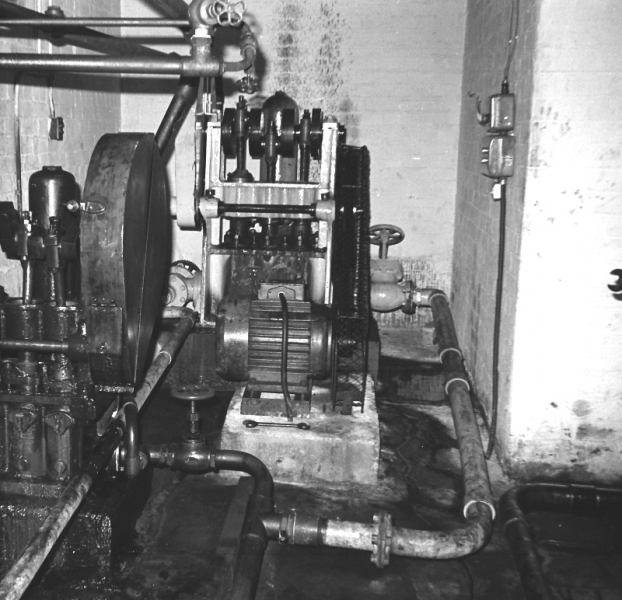

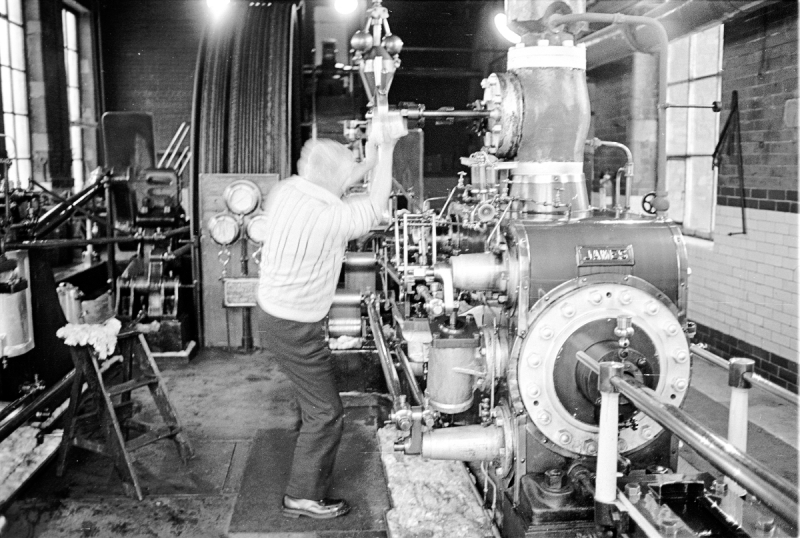

The reason why we became the world’s largest manufacturer of cotton cloth was because we had a demand, a home market and technology responded to this demand by developing a new technology, the steam-driven factory system. We had the necessary capital to invest in this and ample labour. All that was missing was production of the raw material and it is no accident that the meteoric rise of the industry coincided with economic ocean transport largely based on the infamous triangle based on the slave trade and sugar which was the foundation of the development of a port near to us, Liverpool. Throw in canals and railways and we have a very efficient transport system. This edifice of demand, capital and labour drove the development of Empire and this in turn drove the home industry because it expanded the market. At one point the export of cotton goods accounted for more than half of Britain’s exports.

Two factors eroded these advantages, the slow but sure one was the development of textile manufacturing in the developing world, particularly the cotton-producing countries. It’s the banana argument, far more efficient to process the raw material where it was produced if there was adequate technology supported by investment. The second factor was the discontinuity in world trade cause by world war. From 1914 to 1918 the world was starved of British production and this unsatisfied demand triggered production for the home market in the cotton producing countries. Hindsight is 20/20 vision and looking back now it is quite clear that the UK as a whole started to lose ground in general exports, the thing that had made us ‘The Workshop of the World’ after 1870. The cotton textile trade didn’t immediately feel this effect until the Great War intervened, empire trade kept it growing. In July 1920 this edifice cracked and never recovered. The simplistic focus of those affected by the down-turn was ‘foreign competition’ and ‘starvation wages’. Whilst there was a certain amount of truth in both concepts, the real reason was more complicated. This is what I want to try to explain.

In terms of invested capital, availability of labour and a perfected technology the British textile manufacturing system was as near perfect as it could be in 1914. It was supported by a very efficient infrastructure part of which was the reservoir of trading skills and practices on the Royal Exchange in Manchester. Every refinement in contracts, communications and knowledge of the trade was fully exploited. Weaving firms could accept orders, buy yarn, arrange delivery and seek new contracts without stepping off the trading floor. The Manchester Man was the weaving firm’s representative and he was always a man who understood cloth construction, pricing and the contract system. Given sufficient demand the system ran like a well-oiled clock and enabled the smallest manufacturer with say 200 looms to compete with the giants of the trade. In every sense, it was a level playing field and this encouraged independence in the individual firms and supreme confidence in the system. ‘What Manchester did today, the rest of the world did tomorrow’. The basis of all this was buoyant demand and despite temporary lulls in trade this was what the industry enjoyed until 1920.

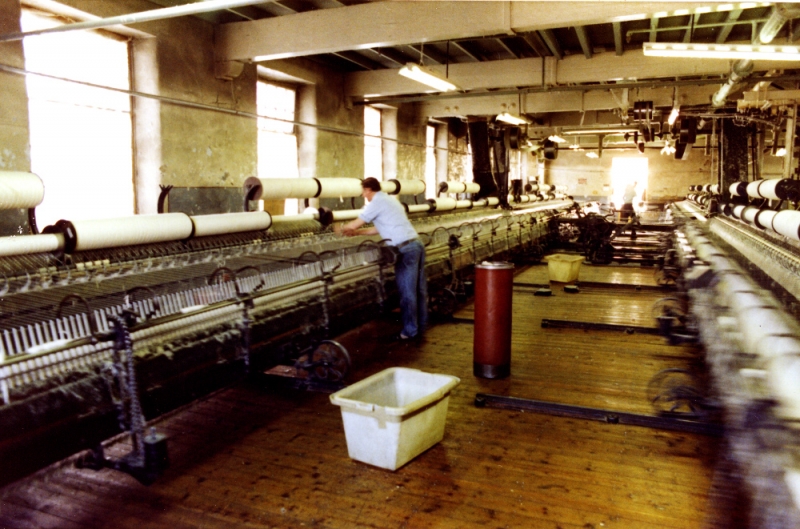

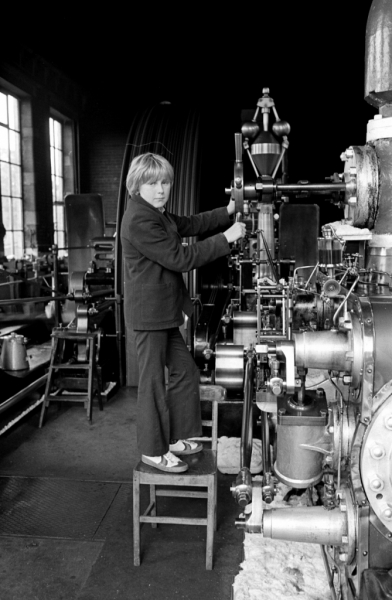

When the trade cracked it wasn’t immediately obvious what was happening. It took a while for the realisation to sink in that it was the export trade which had gone bad on us. This situation wasn’t helped by twenty years of depression in the inter-war period. By the 1920s individual firms had started to fail. Something had to be done. I’m not going to describe in detail all the policy changes that were tried, let’s just agree that the major initiative in the weaving side of the industry was to reduce capacity. In 1939 The Cotton Industry (Re-organisation) Act was passed to implement scrapping and price maintenance schemes which had been agreed by the industry and the Board of Trade but the war intervened and they were never used. Natural wastage accounted for the loss of capacity before WW2 but during the war it was decided that the industry had to be restricted by regulation to ensure that as much industrial capacity as possible was directed to the war effort. In January 1941 it was decreed that capacity should be reduced to 60% of what had been operating in November/December 1940. This was to be achieved by stopping 40% of the machinery in each mill. For reasons that I shall explain in a moment, this was the single worst decision that was made and was to be enshrined in later policies.

The mistake was compounded by the fact that the government had promised that whatever war economies were introduced, the industry would be allowed to return to pre-war trading conditions as soon as circumstances allowed and this became the goal for the individual firms. In 1959 the government put a scheme in place to encourage the scrapping of looms, £80 was paid for a working loom and £50 for an idle one. The intention was that by this means, capacity would be reduced and capital injected into the industry for modernisation.

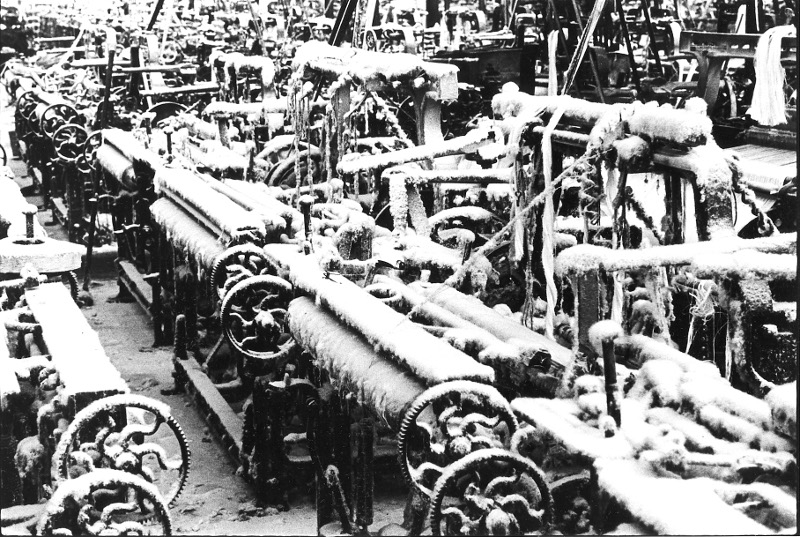

Disused looms in a working shed soon became covered with 'dirt down'. As time went on their number increased.