STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 90301

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

The eradication of Brucellosis was well under way and Demesne became our accredited dealing farm because it was so handy to Gisburn. I saw less of Richard and seldom went to Backridge, he still ran the cattle side of the job but most of my contact was with David. This didn’t seem too important at the time but I have to say there were times when I missed Richard’s skills in man management. He was a hard employer but had the knack of creating a good atmosphere with his men.

Another man whom was affected by the move was John Henry. He had been suffering from poor health, he was having trouble with his breathing and was diagnosed as having Farmer’s Lung. Funny thing about this was that it became a recognised industrial disease and when he went before the medical board for compensation they told him he had asthma! Par for the course. Actually one of his biggest problems was that he was loosing a lot of blood because he had haemorrhoids and when this was cured he improved dramatically but by this time he had decided that he was going to give up farming and go into the building trade. He and Ivy moved to Carleton and John lived there for many years, later as a widower and he died a couple of years ago. I was talking to my eldest daughter who lived in Clitheroe at the time and she told me she had seen Stephen, John Henry and Ivy’s son. She said he still had the scar on his forehead where I cut him open with a muck shovel one day in the Low Barn at Marton. I was giving John a hand to muck out one Wednesday morning and as I turned round to throw a shovel full of muck into the barrow I caught young Stephen on the forehead and gave him a very bad gash. I was terribly upset by this but John was very good about it, he said accidents happen, I can still see the blood pouring out of the lad’s head. When John Henry finished I lost my Wednesday morning mate.

David and I were going up to Lanark one Monday fairly early in 1973. David was driving as we climbed Beattock because we had just changed over at Marchbank where we sometimes dropped calves. We had just got into our stride again and were coming up towards the hotel that lies back from the road on the left when we saw a cloud of dust rising from the south bound carriageway and a large car rolling down the road, I think it was silver colour. As it rolled two bodies and a dog were thrown out. You could tell by the way the bodies hit the road that they were dead, the dog was unharmed and ran away to the north up our side of the carriageway. As I write this I can see the whole thing as clearly as if it was happening now, it was a bad accident and fairly obvious that there were more injured people in the car. David turned to me and said “It does you good to see something like that every now and again.” I told him that I couldn’t answer for him but it had done me no good at all. Later I enquired and all five people in the car were killed. I think it was the rate collector from Falkirk and a dentist friend of his. They were going, with some of their family to Southport to book their holidays and one of the ladies was driving. The car was a Bentley I think and as she was overtaking a slower vehicle she had touched the off side kerb on the carriageway, gone out of control and finished up bouncing off a large rock on the nearside verge. I’ve often wondered since what happened to that dog.

This accident had a very bad effect on me. I had always said that the road was a young man’s job and I would be out before I was forty. All this came flooding back and I had a dream again that had haunted me for quite a few nights after I had written Richard’s car off, it always ended with me in a car rolling over in the road. I was very unsettled and had a lot to think about.

A couple of weeks later I was in the Dog one Sunday having a Guinness with Billy Entwistle, Dan Smith and Jack Platt. Dan and Jack were old drivers from Wild’s Transport in Barlick. Jack asked me what I was going to do next seeing as how I had reached the peak of the profession, I had the biggest wagon, the longest hours and the most miles. They were pulling my leg of course but I gave them a serious reply, I told them I wanted out and the only job I really fancied was running the steam engine at Bancroft Shed I had seen when I was at home with a wing down. Billy Ent said that there was a good chance I could have it, they were looking for a firebeater and the engine tenter retired in July! I went straight home, had a word with Vera and she said she’d go down on Monday and arrange for me to go in and see the management on Wednesday before I went in to work. I went in and saw them and made it quite clear that what I wanted was the job of running the engine. This was agreed and I arranged to start a week the following Monday. I went down to Marton on the Wednesday but didn’t see Richard until the Thursday at Gisburn when I gave him a weeks notice. I don’t think he was all that surprised. I was told later that Wilf Bargh had asked him what he would do without me and he said they would set on two drivers and a mechanic. I don’t know whether this was true or not but it wasn’t far from what was needed.

Years later, Susan, my middle daughter rang me one evening from the Spread-Eagle at Sawley where she was working as a waitress. She said that Richard was speaking at a farmer’s dinner and his subject was the importance of having good men. She said I would have been proud to hear what he had to say about John Henry Pickles and me. That was nice.

On the following Saturday, after working a weeks notice, I left the wagon at Demesne and I think Mary drove me home. Fresh vistas were opening up, I was no longer a wagon driver, I had moved up in the world to being a firebeater!

One last story about the years with Richard. I think it would be about 1970 and I was getting fed up with smoking. I had a bad chest cold regularly and put it down to 40 fags a day, a few cigars and the odd pipe of tobacco. I was climbing the hill out of Coylton one morning after driving up non-stop by myself from Demesne and I threw all the smoking tackle out of the window, everything. Anyone who has tried to end an addiction knows what I went through. Apart from the physical symptoms I became incredibly bad tempered, to the point where Richard told me in Gisburn one day that if I didn’t start again he would sack me! I can’t remember how long I persevered, it seemed like a long time, but a few months later I was early back from Ayr one Tuesday and got into Barlick before 9pm because Ormerod’s sweets and tobacco shop opposite Trinity Church was still open. I went in and got an ounce of Erinmore Flake. When I got in the house I threw it on the table in the kitchen and without saying a word, Vera went upstairs and brought all my pipes down. She brewed a pot of tea for me as I sat there in the chair and had my first smoke for months, it was like heaven! Later she said that the packet of Erinmore was the best thing that had come through the door for months, everyone was pleased and I settled into addiction again, but only the pipe.

Many years later I tried again and did about three months but in the end my doctor told me that there was no way he was going to advise me to start smoking again but the headaches, bad sleep and other symptoms I was suffering were caused by stopping. I gave in, got some tobacco and vowed never to try it again. Funny thing is that I have wonderful health, never cough or get a cold and even the doctor has stopped nagging me now because I appear to have a high tolerance to whatever is bad about smoking. Personally I think it’s the pipe that makes the difference. I hate cigarettes and cigars.

[The good news for you is that we are leaving the road now and moving into a different kettle of fish altogether. Tomorrow we start at Bancroft Shed as a complete novice firebeater! Sorry for the last few days but we need a back story!]

Another man whom was affected by the move was John Henry. He had been suffering from poor health, he was having trouble with his breathing and was diagnosed as having Farmer’s Lung. Funny thing about this was that it became a recognised industrial disease and when he went before the medical board for compensation they told him he had asthma! Par for the course. Actually one of his biggest problems was that he was loosing a lot of blood because he had haemorrhoids and when this was cured he improved dramatically but by this time he had decided that he was going to give up farming and go into the building trade. He and Ivy moved to Carleton and John lived there for many years, later as a widower and he died a couple of years ago. I was talking to my eldest daughter who lived in Clitheroe at the time and she told me she had seen Stephen, John Henry and Ivy’s son. She said he still had the scar on his forehead where I cut him open with a muck shovel one day in the Low Barn at Marton. I was giving John a hand to muck out one Wednesday morning and as I turned round to throw a shovel full of muck into the barrow I caught young Stephen on the forehead and gave him a very bad gash. I was terribly upset by this but John was very good about it, he said accidents happen, I can still see the blood pouring out of the lad’s head. When John Henry finished I lost my Wednesday morning mate.

David and I were going up to Lanark one Monday fairly early in 1973. David was driving as we climbed Beattock because we had just changed over at Marchbank where we sometimes dropped calves. We had just got into our stride again and were coming up towards the hotel that lies back from the road on the left when we saw a cloud of dust rising from the south bound carriageway and a large car rolling down the road, I think it was silver colour. As it rolled two bodies and a dog were thrown out. You could tell by the way the bodies hit the road that they were dead, the dog was unharmed and ran away to the north up our side of the carriageway. As I write this I can see the whole thing as clearly as if it was happening now, it was a bad accident and fairly obvious that there were more injured people in the car. David turned to me and said “It does you good to see something like that every now and again.” I told him that I couldn’t answer for him but it had done me no good at all. Later I enquired and all five people in the car were killed. I think it was the rate collector from Falkirk and a dentist friend of his. They were going, with some of their family to Southport to book their holidays and one of the ladies was driving. The car was a Bentley I think and as she was overtaking a slower vehicle she had touched the off side kerb on the carriageway, gone out of control and finished up bouncing off a large rock on the nearside verge. I’ve often wondered since what happened to that dog.

This accident had a very bad effect on me. I had always said that the road was a young man’s job and I would be out before I was forty. All this came flooding back and I had a dream again that had haunted me for quite a few nights after I had written Richard’s car off, it always ended with me in a car rolling over in the road. I was very unsettled and had a lot to think about.

A couple of weeks later I was in the Dog one Sunday having a Guinness with Billy Entwistle, Dan Smith and Jack Platt. Dan and Jack were old drivers from Wild’s Transport in Barlick. Jack asked me what I was going to do next seeing as how I had reached the peak of the profession, I had the biggest wagon, the longest hours and the most miles. They were pulling my leg of course but I gave them a serious reply, I told them I wanted out and the only job I really fancied was running the steam engine at Bancroft Shed I had seen when I was at home with a wing down. Billy Ent said that there was a good chance I could have it, they were looking for a firebeater and the engine tenter retired in July! I went straight home, had a word with Vera and she said she’d go down on Monday and arrange for me to go in and see the management on Wednesday before I went in to work. I went in and saw them and made it quite clear that what I wanted was the job of running the engine. This was agreed and I arranged to start a week the following Monday. I went down to Marton on the Wednesday but didn’t see Richard until the Thursday at Gisburn when I gave him a weeks notice. I don’t think he was all that surprised. I was told later that Wilf Bargh had asked him what he would do without me and he said they would set on two drivers and a mechanic. I don’t know whether this was true or not but it wasn’t far from what was needed.

Years later, Susan, my middle daughter rang me one evening from the Spread-Eagle at Sawley where she was working as a waitress. She said that Richard was speaking at a farmer’s dinner and his subject was the importance of having good men. She said I would have been proud to hear what he had to say about John Henry Pickles and me. That was nice.

On the following Saturday, after working a weeks notice, I left the wagon at Demesne and I think Mary drove me home. Fresh vistas were opening up, I was no longer a wagon driver, I had moved up in the world to being a firebeater!

One last story about the years with Richard. I think it would be about 1970 and I was getting fed up with smoking. I had a bad chest cold regularly and put it down to 40 fags a day, a few cigars and the odd pipe of tobacco. I was climbing the hill out of Coylton one morning after driving up non-stop by myself from Demesne and I threw all the smoking tackle out of the window, everything. Anyone who has tried to end an addiction knows what I went through. Apart from the physical symptoms I became incredibly bad tempered, to the point where Richard told me in Gisburn one day that if I didn’t start again he would sack me! I can’t remember how long I persevered, it seemed like a long time, but a few months later I was early back from Ayr one Tuesday and got into Barlick before 9pm because Ormerod’s sweets and tobacco shop opposite Trinity Church was still open. I went in and got an ounce of Erinmore Flake. When I got in the house I threw it on the table in the kitchen and without saying a word, Vera went upstairs and brought all my pipes down. She brewed a pot of tea for me as I sat there in the chair and had my first smoke for months, it was like heaven! Later she said that the packet of Erinmore was the best thing that had come through the door for months, everyone was pleased and I settled into addiction again, but only the pipe.

Many years later I tried again and did about three months but in the end my doctor told me that there was no way he was going to advise me to start smoking again but the headaches, bad sleep and other symptoms I was suffering were caused by stopping. I gave in, got some tobacco and vowed never to try it again. Funny thing is that I have wonderful health, never cough or get a cold and even the doctor has stopped nagging me now because I appear to have a high tolerance to whatever is bad about smoking. Personally I think it’s the pipe that makes the difference. I hate cigarettes and cigars.

[The good news for you is that we are leaving the road now and moving into a different kettle of fish altogether. Tomorrow we start at Bancroft Shed as a complete novice firebeater! Sorry for the last few days but we need a back story!]

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 90301

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

BANCROFT SHED 1973 TO 1978

I went to Bancroft Shed that first morning and told George Bleasdale that the best way for him to treat me was as a complete novice. This was no less than the truth, I knew nothing about boilers except that you burned coal in them and made steam. I have to say that in the early days, George, though a bad-tempered old b****r was very good with me. It was in his own interest to have steam produced reliably, his job couldn’t go on without me so he gave me a good introduction to the job of firing the boiler. I hadn’t been there long when he changed his tune, I think the reality of retirement had started to dawn on him and I was the enemy within, he realised that I was the new engine tenter. There was some talk about him already having a man lined up for the job but the management weren’t having any. Sidney Nutter, who ran the office knew a bit about me and I rather think they fancied their chances were a bit better with me than with one of George’s protégés.

What I am going to say now sounds terrible but if I’m not going to tell the truth I might as well not bother. What George knew about the finer points of running a large steam engine could be written in a very slim book. I soon realised that apart from his growing antipathy towards me, there wasn’t going to be much I could learn from him. This didn’t seem too much of a problem, it would all be written down somewhere, all I had to do was find the books.

I attacked the library and inter-library loan and got hold of every book on steam raising and engines that I could lay my hands on. I read the lot and learned many interesting things about the maintenance and construction of chimneys, boilers and engines but nowhere was there any practical information on how you actually ran the damn things, it had never been written down! Evidently it had all been passed on by word of mouth or learned from experience and as there had never been a formal educational course or apprenticeship in running land-based boilers and engines, there was no literature.

In the course of looking for practical information I came across an interesting fact about the status of land-based steam engineers and boiler tenters. In 1897 a Bill was introduced in Parliament, the Steam engines and Boilers (Persons in Charge), which was intended to come into force on January 1st 1898. It wasn’t intended to apply to agriculture, locomotives or road engines but was to set standard qualifications which would lead to certification of engineers and boiler attendants on stationary plant rather like the existing structure of certification applying to marine boilers and engines. Unfortunately, there was a royal visit in London that day that was expected to lead to traffic problems and Parliament adjourned early before the Bill had been discussed. It lost its place in the timetable and was withdrawn on 12 July 1897. If it had gone forward, the craft of tending land based boilers and engines would have been given high status as was the case with marine engineers. However, this never happened and there was never any agreed qualification right to the end of the industry. Unfortunately, though interesting, this wasn’t getting me anywhere, I started to get a bit disheartened!

Then I heard about a man called Newton Pickles. He was the son of John Albert Pickles who was the founder of the engineering firm Henry Brown Sons and Pickles which was still working out of rented premises at Wellhouse Mill in Barlick and was the best firm of millwrights and engineers in the district. At one time they had over a hundred engines on their books and were capable of any repair. I went to see Newton and told him my problems, he told me not to worry, he would set me straight and all I had to do was ask him the questions. He was as good as his word and was to be a tower of strength for me. I can’t emphasise too much how expert he was (he died shortly after I wrote the first version of the memoir in 1999), how generous he was with his time and what a good friend he was every time I thought I was running into trouble. Men like this are very rare in this world and I was incredibly lucky that fate threw us together at just the right time. I know quite a bit about the subject now but I would never have got started if it hadn’t been for Newton Pickles. If you detect a bit of hero worship here, you’re right, as far as engineering is concerned I want to be Newton Pickles when I grow up!

I went to Bancroft Shed that first morning and told George Bleasdale that the best way for him to treat me was as a complete novice. This was no less than the truth, I knew nothing about boilers except that you burned coal in them and made steam. I have to say that in the early days, George, though a bad-tempered old b****r was very good with me. It was in his own interest to have steam produced reliably, his job couldn’t go on without me so he gave me a good introduction to the job of firing the boiler. I hadn’t been there long when he changed his tune, I think the reality of retirement had started to dawn on him and I was the enemy within, he realised that I was the new engine tenter. There was some talk about him already having a man lined up for the job but the management weren’t having any. Sidney Nutter, who ran the office knew a bit about me and I rather think they fancied their chances were a bit better with me than with one of George’s protégés.

What I am going to say now sounds terrible but if I’m not going to tell the truth I might as well not bother. What George knew about the finer points of running a large steam engine could be written in a very slim book. I soon realised that apart from his growing antipathy towards me, there wasn’t going to be much I could learn from him. This didn’t seem too much of a problem, it would all be written down somewhere, all I had to do was find the books.

I attacked the library and inter-library loan and got hold of every book on steam raising and engines that I could lay my hands on. I read the lot and learned many interesting things about the maintenance and construction of chimneys, boilers and engines but nowhere was there any practical information on how you actually ran the damn things, it had never been written down! Evidently it had all been passed on by word of mouth or learned from experience and as there had never been a formal educational course or apprenticeship in running land-based boilers and engines, there was no literature.

In the course of looking for practical information I came across an interesting fact about the status of land-based steam engineers and boiler tenters. In 1897 a Bill was introduced in Parliament, the Steam engines and Boilers (Persons in Charge), which was intended to come into force on January 1st 1898. It wasn’t intended to apply to agriculture, locomotives or road engines but was to set standard qualifications which would lead to certification of engineers and boiler attendants on stationary plant rather like the existing structure of certification applying to marine boilers and engines. Unfortunately, there was a royal visit in London that day that was expected to lead to traffic problems and Parliament adjourned early before the Bill had been discussed. It lost its place in the timetable and was withdrawn on 12 July 1897. If it had gone forward, the craft of tending land based boilers and engines would have been given high status as was the case with marine engineers. However, this never happened and there was never any agreed qualification right to the end of the industry. Unfortunately, though interesting, this wasn’t getting me anywhere, I started to get a bit disheartened!

Then I heard about a man called Newton Pickles. He was the son of John Albert Pickles who was the founder of the engineering firm Henry Brown Sons and Pickles which was still working out of rented premises at Wellhouse Mill in Barlick and was the best firm of millwrights and engineers in the district. At one time they had over a hundred engines on their books and were capable of any repair. I went to see Newton and told him my problems, he told me not to worry, he would set me straight and all I had to do was ask him the questions. He was as good as his word and was to be a tower of strength for me. I can’t emphasise too much how expert he was (he died shortly after I wrote the first version of the memoir in 1999), how generous he was with his time and what a good friend he was every time I thought I was running into trouble. Men like this are very rare in this world and I was incredibly lucky that fate threw us together at just the right time. I know quite a bit about the subject now but I would never have got started if it hadn’t been for Newton Pickles. If you detect a bit of hero worship here, you’re right, as far as engineering is concerned I want to be Newton Pickles when I grow up!

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 90301

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

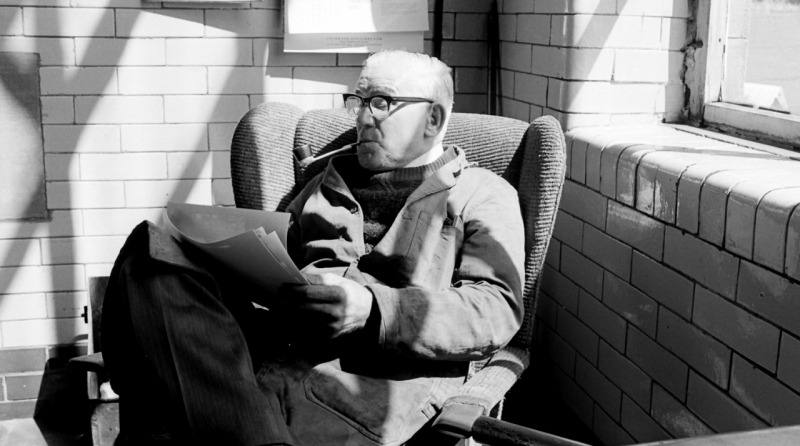

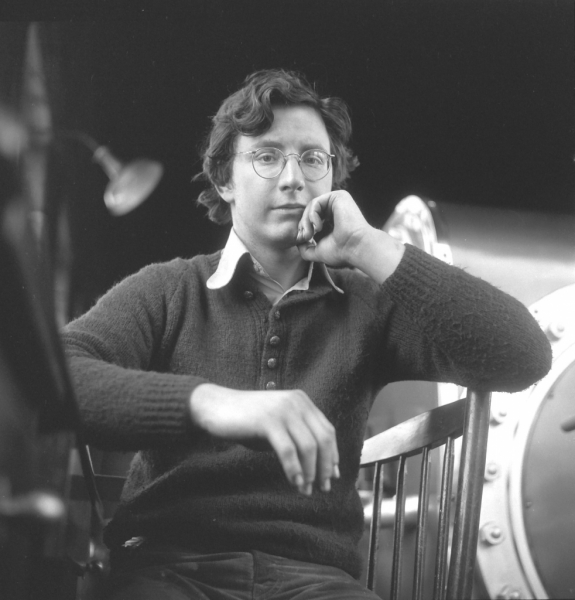

Newton in the engine house.

On the broader front the transition from wagon driving to working at Bancroft completely changed my life. It’s hard to over emphasise the effect, both long and short term, it had on me. Looking back I can see now that there was a head of steam building up in me for change. As is so often true in situations like this, I only vaguely understood this at the time, I think I made as good a fist as I could of managing what was happening to me and think I recognise now some of the places where I went off course a bit but, having said this, I don’t really see how I could have done any better with the knowledge and resources I had at the time. Further, I have no certainty that if I’d done things differently the end result would have been any better. All I am certain of is this, I was dealt a hand of cards and played them as best I could and if I had to go back and do it all over again, I wouldn’t change a thing.

The first major change was that instead of climbing into my place of solitary confinement in the cab of the wagon each morning and assuming complete control of my immediate surroundings for as long as I stayed there, I walked down the field, climbed over the fence and became part of the wonderful mechanism called Bancroft Shed. I wasn’t the Lone Ranger any more, what I did affected everybody else and they in turn affected my life, it was a lot nearer to the real world, I know now that this was a very powerful engine of change for me but I hadn’t worked it out then.

The older I get the more I realise that the perceived quality of my life depends on the degree to which I have control. Show me a situation and I’ll demonstrate that if you pursue it to its roots it always ends up as an issue of control. In the wagon I had almost perfect control of my life, I was responsible for the existence of everybody and everything in my sphere of influence. If I made a wrong move I could die or destroy property or kill somebody. I believe that this is the factor that explains most of what people see as altered behaviour when driving a vehicle. I only had one master, the physical laws of the world, I couldn’t fight time, weight, gradient, weather or distance, these had to be managed but these variables are easily quantified, they are known, there are no surprises so my job, which was to work with them, became logical and there was a degree of certainty about the outcome which isn’t often met with in this world. I believe that this is why I like working with machines so much because the same rules apply. Conversely, it might be the explanation why I am so bad with human beings! Obviously I hate to admit this and can’t quite square up why this doesn’t apply to children and animals, I have no problems at all with them, perhaps it’s because they are working on a much simpler level and have more easily identifiable agendas. Then again, I might be talking about women! I think you have enough clues here to grasp the sense of what I am trying to convey, I’m not going to make what I would see as a mistake at this point by trying to take this analysis too far. It would be misleading because much of my refined thought about these matters is the result of circumstances which, at this point in my life, are still far in the future, I’ll only add one rider at this point, I think I was a slow developer!

I started at the mill in late spring 1973 and we were out of the heating season. The significance of this is that I was in plenty of time if I started at seven in the morning. Couple this with the fact that I was home by five o’clock in the evening and you have the first major change, I could be a proper member of the family again. My weekends became my own and the long summer evenings were available for all sorts of pleasant little tasks which I had never been able to attend to before. It was wonderful for me and I think an improvement for everybody else as well, certainly, at this distance in time, my impression is that it was a very happy time at Hey Farm. Mother had settled down well in her house in Avon Drive after father’s death and there was plenty of communication between us. My association with Drinkall’s hadn’t ended either, Richard asked me whether I’d take responsibility for maintenance of the wagons just as before and I was glad to do it. For a start, it was a useful supplement to our income and I enjoyed the work and the continued contact with my friends.

There was another consequence which followed working at the mill. I started to build a new orbit of friends and acquaintances. People who know me are often surprised at my lack of knowledge of Barlick and its inhabitants between 1960 and 1973. Not surprising really when you consider that the only times I was in the town was during the hours of darkness! A bit of an exaggeration I know but beyond purely family contacts, I didn’t live in the town I just slept there if I was lucky, my home town was mainland Britain. This all changed, I came into contact with everyone in the mill for a start off, then there were the regular visitors at the boiler house. In this respect, Bancroft was like the industries I knew as a child, if you were an outsider and wanted to visit your friend or relation during working hours you just walked in the mill and had a conversation. There was no security, no barrier, you just walked in, children would come in to see their Aunts, I even saw a mail order delivery man come in one day to deliver a parcel to a weaver! George and I in particular were a law unto ourselves, if we wanted ten minutes to go to the shop or run an errand we covered for each other and went and did whatever we had to do. The boiler house was almost like a local meeting place, my mates would call in and have a word if they were passing and I have had many a cup of tea sat on a stone ledge in the mill yard while the job took care of itself. All this was a tremendous change, when you’re driving you have to exercise total concentration for hours at a stretch. Vera will tell you that I didn’t even like to talk while I was driving the family, I couldn’t afford the distraction. I could have a five minute spell and a crack any time I wanted and relax when I was running the boiler.

Another delight during good weather was that you could always take time to go for a walk out to the lodge where we stored the water for the condenser on the engine and have a look at the moorhens and ducks. If I lifted my eyes I was looking at Hey Farm land with our cattle grazing quietly away in the field, I wasn’t confined at all. In bad weather I still got plenty of exercise because it was essential that as firebeater I knew what was going on in the mill so that I could assess steam demand. I used to go and have a walk round frequently during the day to see who was doing what and there was plenty of opportunity for a crack with the weavers or the tacklers while on my rounds and this passed the time on nicely.

Mind you, increased contact with people had disadvantages as well! I can’t remember how it came about but I met the husband of one of the teachers at Church School, Raymond Rance. We got talking and it turned out that he was in a bit of trouble, he and his father were in partnership as builders and they had taken on what was, for them, quite a big contract. At this time Burnley Council was widening the main road from the Prairie at Reedley to Duke Bar and as part of the contract they had demolished the end two houses of every row butting on to the road on the left hand side going towards Burnley. Raymond and his dad had the job of building a new skin on the end of each row of houses and repairing the roofs. They only had two to do before they got paid but had run out of credit and materials. Raymond wasn’t a mate of mine but there was a connection in that his wife was teaching our children so I offered to help him out. I said he could buy the timber that I had bought when I was thinking of doing the roof of the farm, I told him he could have it for what I paid for it plus 50%. It was still cheap because I had bought it at a very good price and timber prices had risen sharply in the two years it had been sitting sheeted up in the garden. I said that if it helped he could have it and pay me when they drew off the Council. He accepted with glee and took the timber away.

A couple of months afterwards I was walking up Folly Lane past Folly Cottages where he lived and I met him in the road. I asked him when he would be able to pay me and he said he wasn’t going to give me any money, he said there was nothing I could do about it and so there was no point bothering him. To say I was surprised would be to put it mildly! I told him that I suspected he had just made the biggest mistake of his life and that if he didn’t bring the money to Hey Farm by five that evening I would take steps which would astound him! He never came so the following day I went to see Keith McCann my solicitor and asked him what it would cost me to bankrupt Rance. “Not a lot. You can join in with the others!” So I did and it cost me £40. Rance and his father went down on the 26th of June 1975 for £18,462 and had no assets to cover this, everything was in their wives’ names. The thing that really annoyed me when I got the Summary of Statement of the case and the Official Receiver’s Observations was that they admitted knowing they were insolvent in August 1974, well before I helped them out. I see Rance occasionally in the town and wonder how anybody can be as bare faced as he is, I did him a good turn when he needed it and he dumped all over me. I have a theory that it all levels out in the end and I wouldn’t like to be in his shoes when it does. One thing is sure and certain, Vera and I lost out but we never lost any sleep, Vera was devastated at the time, she couldn’t believe that anyone could be so heartless. Seeing her lose her faith like that hurt me more than the money and I will never, ever, forgive Mr Raymond Rance. Funnily enough, this incident did me a favour later but we’ll come to that at the proper time.

There is a later consequence to add here. I happened to be sat in the Cross Keys pub one evening talking to Alan Parker my old tanker driver mate from West Marton and there was what I call a ‘boomer’ at the next table, someone talking so loudly that his voice was distracting us from our conversation. The gist of what he was saying was how clever he had been in his business dealings and how much money he was making. I hadn’t recognised the voice but at one point I turned in my chair to see who the loud mouth was. You’ve guessed it, it was Raymond Rance. I leaned over and in a loud voice informed him that seeing as how he was doing so well, he might like to ease his conscience by giving me the £280 he had cheated me out of over 25 years ago when I helped him out of a tight spot, and by the way, 25 years interest at bank rate would be nice as well. He never said a word, just got up and walked out. Everyone was looking at me as though I had done something terrible so I informed everyone within earshot what had happened and that if they were thinking of trusting Raymond, have another think about it because the man was a crook. I don’t think I was being petty, it had to be said and I know that if I hadn’t said something there and then I’d regret it all my life. To the best of my knowledge he is still alive and perhaps someone will bring this to his attention. It isn’t too late Raymond and I have all the original paperwork, live with it or remedy it!

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 90301

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

When I went to Bancroft I was 37 years old. Apart from the long term problem of a back damaged by too much lifting in the early days I was in good health. I was as strong as a horse, I had no problem lifting 300 lbs and would throw a 45 gallon drum of oil upright from a horizontal position by myself, these drums weighed over 500 lbs. Firing the boiler involved a lot of shovelling of coal, I would think nothing of shifting five tons of coal into the bunker after the coal wagon had tipped, we couldn’t get it all in straight from the wagon and there was usually some to tidy up afterwards so that the boiler house door could be shut and locked.

On the whole then, the transition went well. I never for one minute questioned my decision to move and I don’t think it caused any problems at home either, what we had to report was progress, everything in the garden was looking fine!

THE WORK AT BANCROFT

Bancroft Shed was built by James Nutter with the profits he made from manufacturing in the room and power system whereby he rented accommodation in other local mills. Like other local manufacturers he found himself in a position at the beginning of the 20th century where he could afford to build his own mill and this was an economic proposition as the long term cost was less than paying rent. He started to build in 1914, the last weaving shed to be built in Barlick. Due to the war the shed wasn’t finished until March 1920 when it was opened with all due ceremony and started to produce cloth. You’ll notice as I tell this story that some mills are referred to as mills and others as sheds. Almost without exception the distinction is that a mill is a factory that once included spinning in its activities and a shed was built solely for weaving. In the early days of the industry mills often spun their own yarn but as the industry developed firms began to specialise to reduce costs and spinning died out in Barlick, it was cheaper to buy the yarn in from South Lancashire than manufacture it. Bancroft never had any spinning and so was always known as a mill but named Bancroft Shed. (In 2009 I published a book called ‘Bancroft Shed’ which describes what went on in the shed and the people who worked there. If you want the inside story go to Lulu.com and buy it. Alternatively there is a copy in the local library.)

The prime necessity for a steam driven mill is a reliable supply of water for the condenser pond. This water is used to cool the condenser on the engine which is essential to economic running. The pond or lodge was in effect a heat sink for the condenser. The water supply at Bancroft was Gillian’s Beck, the same beck that ran through the field at Hey Farm.

The main element of a mill like Bancroft is the large, single storey weaving shed sunk into the hillside. This was fronted by a two storey section which had the warehouse on the bottom floor and yarn and beam preparation departments upstairs. On the left hand end of the mill was an office block and on the right hand, the engine house with the boiler house and chimney behind. The construction of the building was absolutely typical, cast iron frame, stone walls and blue slate roofs. The lodge lay in front of the mill and there was space down the right hand side next to the boiler house and chimney for a large coal reserve in case there was any interruption in fuel supply.

The engine house was about the size of a small chapel and looked very much like one because of its large window in the north end. This window had a very practical purpose, if removed it would permit egress for the largest part of the engine in case of the need for repairs. Behind the engine house was the boiler house which contained the coal bunker which would hold about twenty tons of coal, the Lancashire boiler, the economisers and a smaller, disused Cornish boiler which had been installed after WWII to increase steam capacity but had never been a success because of lack of draught from the chimney. The 130ft high chimney stood behind the boiler house and was the exhaust for the gases produced when coal was burnt in the boiler to raise steam.

The man who looked after the engine was traditionally known as the ‘tenter’ or watcher. The man who fired the boiler was known locally as the ‘firebeater’, in other areas he would be called a stoker.

My job as firebeater was to raise steam by burning coal in the boiler to supply all the needs of the mill keeping a constant pressure of about 140psi. The problem the firebeater continually had to solve was that the demand for steam fluctuated because it was used for process and heating as well as driving the engine. The demand from the engine could alter suddenly if the lights had to be put on because we generated our own electricity and this could increase the load on the engine by 20%. I soon learned that the secret was anticipation and the more I knew about what was happening in the mill or the weather outside the better the estimates I could make of future demand. I had to predict ahead because one of the characteristics of a Lancashire boiler is that it is slow to react, if I wanted more steam I had to act 15 minutes before the demand came on. Once I had cracked the routine and the technicalities, which didn’t take long, the job became easy and a joy because you always had to be thinking ahead. It became a matter of pride to me that steam didn’t vary by more than five pounds unless there was an entirely unforeseen circumstance.

The engine fascinated me. If ever there was an example of pure, concentrated engineering, a working steam engine has to come somewhere near it. It embodied all the laws of thermodynamics, gas theory and mechanics. It was, on the surface, so simple and yet the more you studied it the more complicated it became. Imagine peeling an onion and on each succeeding skin you find writing, by layer three you are the stage of ‘Gone With the Wind’, a couple of layers later you are on a complete copy of the Bible and shortly after that you are expecting the complete ‘Encyclopaedia Britannica’! I remember reading a report once of the retirement speech of Churchward, one of the great railway Chief Engineers, he said it was a pity he was retiring because after 50 years in the job he felt he was on the verge of understanding the simple slide valve! I think I know what he meant, I’m sure this applies to many more situations in life, if not all, but the steam engine brings it home to you very forcibly.

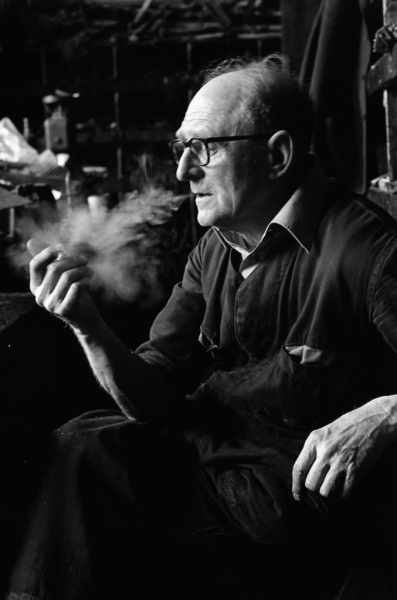

My new world!

On the whole then, the transition went well. I never for one minute questioned my decision to move and I don’t think it caused any problems at home either, what we had to report was progress, everything in the garden was looking fine!

THE WORK AT BANCROFT

Bancroft Shed was built by James Nutter with the profits he made from manufacturing in the room and power system whereby he rented accommodation in other local mills. Like other local manufacturers he found himself in a position at the beginning of the 20th century where he could afford to build his own mill and this was an economic proposition as the long term cost was less than paying rent. He started to build in 1914, the last weaving shed to be built in Barlick. Due to the war the shed wasn’t finished until March 1920 when it was opened with all due ceremony and started to produce cloth. You’ll notice as I tell this story that some mills are referred to as mills and others as sheds. Almost without exception the distinction is that a mill is a factory that once included spinning in its activities and a shed was built solely for weaving. In the early days of the industry mills often spun their own yarn but as the industry developed firms began to specialise to reduce costs and spinning died out in Barlick, it was cheaper to buy the yarn in from South Lancashire than manufacture it. Bancroft never had any spinning and so was always known as a mill but named Bancroft Shed. (In 2009 I published a book called ‘Bancroft Shed’ which describes what went on in the shed and the people who worked there. If you want the inside story go to Lulu.com and buy it. Alternatively there is a copy in the local library.)

The prime necessity for a steam driven mill is a reliable supply of water for the condenser pond. This water is used to cool the condenser on the engine which is essential to economic running. The pond or lodge was in effect a heat sink for the condenser. The water supply at Bancroft was Gillian’s Beck, the same beck that ran through the field at Hey Farm.

The main element of a mill like Bancroft is the large, single storey weaving shed sunk into the hillside. This was fronted by a two storey section which had the warehouse on the bottom floor and yarn and beam preparation departments upstairs. On the left hand end of the mill was an office block and on the right hand, the engine house with the boiler house and chimney behind. The construction of the building was absolutely typical, cast iron frame, stone walls and blue slate roofs. The lodge lay in front of the mill and there was space down the right hand side next to the boiler house and chimney for a large coal reserve in case there was any interruption in fuel supply.

The engine house was about the size of a small chapel and looked very much like one because of its large window in the north end. This window had a very practical purpose, if removed it would permit egress for the largest part of the engine in case of the need for repairs. Behind the engine house was the boiler house which contained the coal bunker which would hold about twenty tons of coal, the Lancashire boiler, the economisers and a smaller, disused Cornish boiler which had been installed after WWII to increase steam capacity but had never been a success because of lack of draught from the chimney. The 130ft high chimney stood behind the boiler house and was the exhaust for the gases produced when coal was burnt in the boiler to raise steam.

The man who looked after the engine was traditionally known as the ‘tenter’ or watcher. The man who fired the boiler was known locally as the ‘firebeater’, in other areas he would be called a stoker.

My job as firebeater was to raise steam by burning coal in the boiler to supply all the needs of the mill keeping a constant pressure of about 140psi. The problem the firebeater continually had to solve was that the demand for steam fluctuated because it was used for process and heating as well as driving the engine. The demand from the engine could alter suddenly if the lights had to be put on because we generated our own electricity and this could increase the load on the engine by 20%. I soon learned that the secret was anticipation and the more I knew about what was happening in the mill or the weather outside the better the estimates I could make of future demand. I had to predict ahead because one of the characteristics of a Lancashire boiler is that it is slow to react, if I wanted more steam I had to act 15 minutes before the demand came on. Once I had cracked the routine and the technicalities, which didn’t take long, the job became easy and a joy because you always had to be thinking ahead. It became a matter of pride to me that steam didn’t vary by more than five pounds unless there was an entirely unforeseen circumstance.

The engine fascinated me. If ever there was an example of pure, concentrated engineering, a working steam engine has to come somewhere near it. It embodied all the laws of thermodynamics, gas theory and mechanics. It was, on the surface, so simple and yet the more you studied it the more complicated it became. Imagine peeling an onion and on each succeeding skin you find writing, by layer three you are the stage of ‘Gone With the Wind’, a couple of layers later you are on a complete copy of the Bible and shortly after that you are expecting the complete ‘Encyclopaedia Britannica’! I remember reading a report once of the retirement speech of Churchward, one of the great railway Chief Engineers, he said it was a pity he was retiring because after 50 years in the job he felt he was on the verge of understanding the simple slide valve! I think I know what he meant, I’m sure this applies to many more situations in life, if not all, but the steam engine brings it home to you very forcibly.

My new world!

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 90301

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

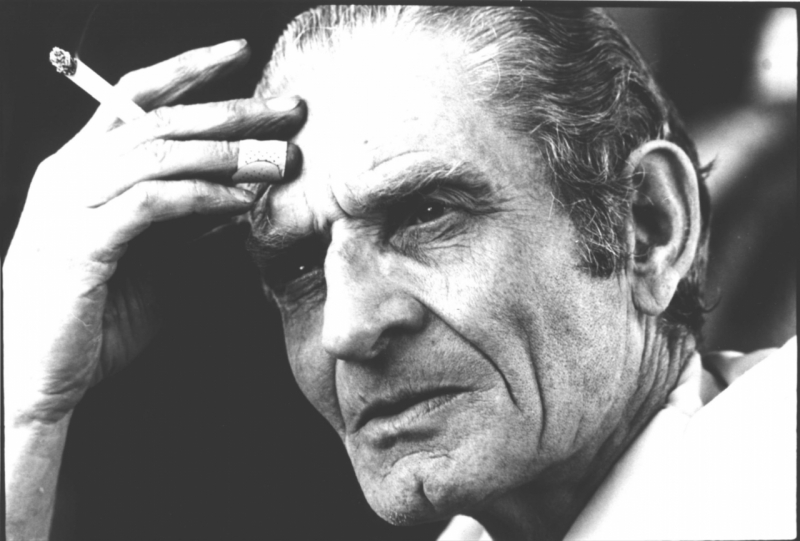

Ernie Roberts, tackler and gent!

A favourite calling shop in my peregrinations round the mill was the tackler’s cabin in the warehouse. The tacklers were the men who tuned the looms and kept them in order for the weavers, they each had their own set of looms, about 100 each, and knew the looms and the weavers intimately. I soon made a very good friend in Ernie Roberts, he was a marvellous bloke who had been ‘woven out’ five times. In other words he had been working at a mill where they were closing down and because of the nature of the job, the looms gradually reduce in number until there are none left, something like a slow death. Despite this, Ernie was still in the industry and had retained his sense of humour. He eventually reached the stage where his house was paid for and he could retire gracefully. After six months of well-earned rest he got a brain tumour and died a horrible death. It was so bloody unfair. It reinforced my oft-repeated contention that someone, somewhere has a very strange sense of humour!

I spent a lot of time with Ernie before he died and he was one of the first people I taped when I decided to record the industry. He told me some marvellous stories about his war service but two stand out in particular. Ernie was in Signals, he said that apart from shooting on the range he never fired his rifle once in anger! He was in India and Burma and on the quiet he had a hard war. He told me once that he and his mate Charlie were in a slit trench and there was a lot of ‘incoming mail’. As they cowered down with shells and mortars bombs raining down on their position Charlie said to him “Do you know what blood smells like?” Ernie said he didn’t and asked Charlie why he had put the question. “Because if it smells like shit, th’art wounded!” Another time, they were paraded and a man came and addressed them about the necessity to take imaginative measures to beat the Japanese. At the end of his speech he asked for volunteers, Charlie was about to take one pace forward when Ernie grabbed his shirt. “Stay where you are, this b****r’s mad!” It turned out that his name was Orde Wingate and he was calling for volunteers for the Chindits. He and his volunteers marched off into the jungle to almost certain death and very few of them survived, Ernie was dead right. Charlie came to a sad end. Ernie had been in his dugout most of the night and Charlie came to relieve him, “Sheath your sword Roberts, you’ve done enough for one night!” Ernie went to the cookhouse for a cup of tea but before he had finished it the dugout Charlie was in got a direct hit from a mortar bomb and he was killed.

Ernie got Black Water Fever. He was sent back to a forward hospital for assessment and one of the first examinations was of his stool. Ernie went off to a small canvas tent with a tin to produce the sample, one of the main indicators of Black Water Fever is very thin, black, evil-smelling motions, hence the name. He filled his tin and two blokes who were in there from a Highland regiment wrinkled their noses when they saw it and asked what it was. Ernie told them and added that it was a Blighty Ticket, in other words he would be invalided home as there was no cure. Five minutes later he emerged from the tent ten shillings richer having provided the other two with a sample. They all went home together. Ernie had what he called bootlace diarrhoea until the day he died, there are still people walking round carrying the burdens of the war like Ernie Roberts and Bill Robertshaw and we should never forget.

Back at the farm we were now without any form of transport. I decided we had better do something about this and so I bought two moribund Ford Anglias. The idea was to make one good car out of the two so I set to work in my spare time. I partially succeeded in the end but have to admit that even when I had finished, our ‘new’ car left a lot to be desired. Nevertheless, we were mobile and visits to my sister in Stockport and shopping trips to Burnley became possible. It’s perhaps indicative of how little I thought about the result that there is no picture of it in my negative files!

At this time I would occasionally go to work in the car if it was raining or if I had an errand to run during the day. I was going up towards the mill one morning and met Raymond Rance coming the opposite way in a brand new Morris Marina! This absolutely incensed me. Here I was, doing everything right and as honest as the day was long and there was Rance, who still owed me for the timber he had stolen off me and gone bankrupt into the bargain, riding round in a new car while I was trailing round in a scrapper! I couldn’t help tending towards the conclusion that something was wrong somewhere. A few days afterwards, Vera and I had been shopping somewhere Burnley way and as we returned home over Whitemoor Vera asked me why the car was making a funny noise. I told her I suspected it had broken in two and the noise she could hear was the gearbox dragging on the floor. I got it home, had a look underneath and welded in a temporary solution but my mind was racing now!

I went to several people who’s opinions I respected and told them of my problem and what I had in mind as a solution. They all agreed that I was thinking correctly and so, after consulting with Vera I sold the big field to our neighbour, young Sid Demain and went out and bought a brand new 12 seater diesel Land Rover Safari! It cost £4,800, more than twice what I had paid for the farm but was a wonderful investment, we were really mobile now. My idea was that it would be a safe if not speedy vehicle, it would have plenty of room for the kids and it could be used for other purposes as well. I could see that the mill wasn’t going to last for ever and a good utility vehicle like this would make an ideal mobile workshop. Old Arthur Entwistle thoroughly approved and we got to the stage where we went on visits to see him and Amy and eventually stayed at his son’s house as well.

Shortly after I got the Land Rover I did something which even I find hard to believe now. Vera came out to the workshop one Saturday morning a couple of months after we had got the motor and found me lifting the engine out of it! She asked me what I was doing and I said I wasn’t satisfied with the engine, they had built it wrong and so I was going to strip it down, rebuild it and see if it was any better! She didn’t argue, she left me to it but I can well imagine that even Vera thought I’d gone too far this time. It took me two days but I completely stripped the engine and rebuilt it with one or two adjustments to my own specifications. I should say at this point I wasn’t working completely in the dark. For some time I had been reconditioning Rover diesel engines for Walt Johnson at Crawshawbooth where I had bought the motor and had gained a lot of insight into the basic faults of the engine. Walt always said my rebuilds were better than Rover’s. When I had it laced up together again I took it out for a run and what a difference! It ran quieter, had more power and used less diesel, game set and match to Stanley! (Could it have been an issue of control?)

I had just about settled in at the mill when in December 1973 we had the fuel crisis and the three day week. There were power cuts and we were using oil lamps at times at the farm. We got right down to the bottom of the stock pile and I was burning coal which was sent over from the United States after the war. It was lousy stuff, I had to mix it with good coal to get it to burn! The paradox was that we were immune to power cuts as long as we had coal but it was strictly rationed. We never knew when coal was coming, we just had to take our turn. One day a wagon drew into the yard and asked if we were Bankfield Mill. I assumed temporary deafness and said yes and we backed him in and tipped his load. It was Sutton Manor Pit washed singles from over St Helens way and was wonderful steam coal. Of course I knew that he’d made a mistake, Bankfield Shed was the Rolls Royce factory and we had pinched 20 tons of their coal! It took about five days for the penny to drop but by that time it was too late to do anything about it, we had burned it. I left it to the management to sort out and carried on as best as I could.

The next milestone was July 1974 when George retired and I became engineer. We had advertised for a firebeater and a young lad called Ben Gregory applied and I gave him the job. He knew nothing but was young and prepared to learn. It was the Annual Wakes Week holidays, I was master of all I surveyed in the engine house and had my own labourer! It struck me at the time that there must be thousands of people in the country who would have given their eye teeth to have my job. We were one of the last engines to run and tenters were a dying breed. Another thought that came to me was that I must be the youngest bloke left in the country running an engine commercially and that one day, with a bit of luck, I would be the last!

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 90301

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

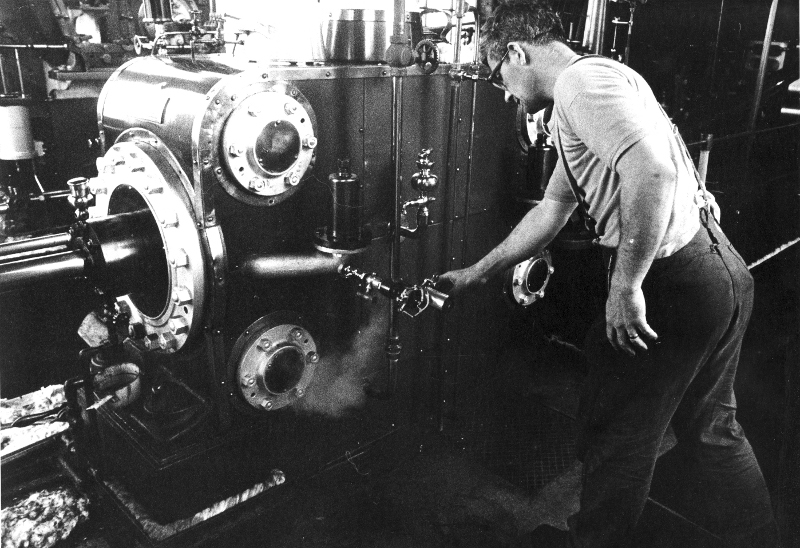

My new domain. A bit bigger than the cab of a wagon but I still had a good view!

ENGINEER AT BANCROFT SHED

The first thing I had to do when George retired was supervise the annual shut down and maintenance work on the boiler and engine. The boiler was under statutory insurance and had to be inspected at least every 14 months, in effect this meant every year at Barlick holidays. The insurance surveyor would let me know what items he wanted to inspect and I would have them stripped out and ready for him when he came. At the same time I would prepare the boiler for the flue men who came in to clean all the flue dust out of the flues round the boiler. If any scaling needed doing in the boiler they would do this as well. The object of the exercise was to have all the flues and the interior of the boiler clean and in fit condition to inspect by about Wednesday of the first week of the holidays, this gave time for any repairs or replacements before the mill opened again.

The first part of this was to blow the boiler down on the last day of work before the holidays started. We used to do this as soon as the weavers were out of the shed. This was often before official stopping time because it was an accepted fact that as soon as the weavers had their holiday pay in their hands they were off. Many a time we didn’t start again after dinner, this was a good thing for me and the firebeater as it gave us a good start.

By the time the weavers were gone, the firebeater would have drawn his fires and ashed out, in other words, all the clinker and ash was removed from the two furnaces. Then I would go on the top of the boiler and open the low water safety valve, propping the lever up with a couple of bricks, this allowed the steam in the boiler to escape to the open air through a three inch diameter pipe. This made a tremendous roar and signalled to the whole of Barlick that we were on holiday! I have a story for you about this. I forget exactly which year it was but it was the last day before the annual fortnight’s break and we were doing our usual routine, draw the fires and ash out before dinner because there would be no one working after as they’d drawn their pay. I was sat in the engine house having a brew and a sandwich when Jim Pollard the weaving manager, came in. He looked a bit harassed so I asked him what was up. He said the weavers were having a dispute with the management about holiday pay and the upshot was that until this was settled, they wouldn’t be going home as they were frightened of losing their pay. In other words I had to run the engine after lunch!

I told Jim we had a bit of a problem, we had drawn the fires. He said we’d have to relight them but there was no way I was going to do this. I went down and had a look and we had plenty of water and about 120psi on so I shut the dampers to stop the draught cooling the boiler and told Jim we’d run as long as we had steam, there wasn’t time to relight. He went off into the mill and we started up at 13:30 as usual. The point of this story is that we ran until 15:30 with no fire in, even I was amazed how little steam the engine was using. It reinforced a theory I had held for a long time that the place the heat went to was keeping the settings hot and making up heat losses, the engine hardly used any! We got away with this because as the pressure dropped the superheated water in the boiler effervesced and released more steam. This was the great advantage of the Lancashire boiler, its great water capacity made it slow to react to firing but ensured that there was a tremendous reserve of steam which could be used to iron out fluctuations in demand. If a situation arose where you were hard pressed to make steam as fast as it was used, you simply shut down the feed water and allowed the water level in the boiler to drop slowly. Governing the boiler with the feed pump against a fire adjusted to its most efficient level was the most economical way to run the boiler but depended on having a very reliable pump.

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 90301

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

Anyway, back to our closing down routine. When the pressure had dropped to about 60psi I would go into the boiler house and open the blow-down valve under the front of the boiler. This allowed what water was left in the boiler to drain away under pressure, as the water drained out it carried much of the sediment which builds up in the boiler out with it. At the same time I would go out to the dam and open the clough which let all the water in the dam flow away down the beck, this took a lot of muck out of the dam with it.

While this was happening the firebeater and I would be having a brew. As soon as things quietened down we would go on top of the boiler and open the large manhole on top of the boiler and lift the lid out of the way with a block and tackle. This was a ticklish job because as soon as you opened the lid, scalding vapour would pour out until all the water had dried off the inside of the boiler. The trick was to knock the lid in and leave it hanging on the tackle until things had cooled down a bit. Then we would take a similar manhole out from the front of the boiler at the bottom and check that all the chimney dampers were wide open. At this point we left the boiler with cold air circulating through all the flues and through the water space of the boiler itself, the object was to have the boiler and settings cool enough next morning for the flue men to get in and do their stuff. I would often come back last thing at night and knock the flue doors off under the front plates so as to encourage better circulation through the side and sole flues. The cooler it was for my flue men the better the job they would do for me, remember that the brickwork in the settings and the flue dust in the flues was still red-hot at this point.

The following morning Ben and I were in for eight o’clock and had everything opened up ready for the arrival of Mr Charles Sutton of Brierfield who’s firm, Weldone would clean the flues. His son Pat worked with him together with Jack who was no relation but had been with them for years. Charlie Sutton was one of the world’s great characters, Jack, his man was possibly the hardest man I have ever seen and Pat his son was a good worker but didn’t have his heart in the job. I don’t blame him, flueing is one of the worst jobs in the world. Later he joined the army and went in the Military Police, he’s a bobby in Clitheroe now.

Daniel Meadows did pics of them flueing. This gives a good idea of what a horrible job it was.

There’s nothing complicated about what fluers do. They go into the flues, gather up the flue dust which is the fine ash carried over by the draught through the firebox which settles in the flue spaces round the boiler and bucket it or shovel it out of the nearest hole to the outside world. Two men work in the flues and one outside carrying away in the barrow to the ash heap outside. We piled the flue dust separately as when it was weathered it was ideal for laying stone flags and we used to give it away to anyone who wanted some. Incidentally, we provided another service free while we were running, if your dog or cat died we would cremate it in the fires! The only thing about this was that we wouldn’t do a cremation within fourteen days of flueing because it wasn’t fair on the fluers, the smell hung in the flues for over a week despite the high temperatures. Charlie used to tell us that in the old days other things got cremated in the flues as well, he reckoned he once found melted gold in the downtake of a boiler and said that more than one nagging wife had left the world that way!

Once the flues were dealt with, this took about four hours, Charlie and his men had a brew and then started on the scale. A boiler is like a kettle and if the water isn’t properly treated, scale builds up on the internal surfaces and interferes with heat transmission and inspection. Ideally, a sixteenth of an inch is just right, this actually protects the boiler plates. When I took over at Bancroft we had a bad scale build up and we had to spend a day and a half chipping inside the boiler to get it in good enough condition to inspect, I made a mental note to sort out the water treatment and get the scale down. It was over 120 degrees Fahrenheit in the boiler and scaling is hard work in a confined space. I could do about an hour but Jack could go on for ever it seemed. My earlier assessment of how hard he was is based on things like this, he just didn’t give up!

While this was happening the firebeater and I would be having a brew. As soon as things quietened down we would go on top of the boiler and open the large manhole on top of the boiler and lift the lid out of the way with a block and tackle. This was a ticklish job because as soon as you opened the lid, scalding vapour would pour out until all the water had dried off the inside of the boiler. The trick was to knock the lid in and leave it hanging on the tackle until things had cooled down a bit. Then we would take a similar manhole out from the front of the boiler at the bottom and check that all the chimney dampers were wide open. At this point we left the boiler with cold air circulating through all the flues and through the water space of the boiler itself, the object was to have the boiler and settings cool enough next morning for the flue men to get in and do their stuff. I would often come back last thing at night and knock the flue doors off under the front plates so as to encourage better circulation through the side and sole flues. The cooler it was for my flue men the better the job they would do for me, remember that the brickwork in the settings and the flue dust in the flues was still red-hot at this point.

The following morning Ben and I were in for eight o’clock and had everything opened up ready for the arrival of Mr Charles Sutton of Brierfield who’s firm, Weldone would clean the flues. His son Pat worked with him together with Jack who was no relation but had been with them for years. Charlie Sutton was one of the world’s great characters, Jack, his man was possibly the hardest man I have ever seen and Pat his son was a good worker but didn’t have his heart in the job. I don’t blame him, flueing is one of the worst jobs in the world. Later he joined the army and went in the Military Police, he’s a bobby in Clitheroe now.

Daniel Meadows did pics of them flueing. This gives a good idea of what a horrible job it was.

There’s nothing complicated about what fluers do. They go into the flues, gather up the flue dust which is the fine ash carried over by the draught through the firebox which settles in the flue spaces round the boiler and bucket it or shovel it out of the nearest hole to the outside world. Two men work in the flues and one outside carrying away in the barrow to the ash heap outside. We piled the flue dust separately as when it was weathered it was ideal for laying stone flags and we used to give it away to anyone who wanted some. Incidentally, we provided another service free while we were running, if your dog or cat died we would cremate it in the fires! The only thing about this was that we wouldn’t do a cremation within fourteen days of flueing because it wasn’t fair on the fluers, the smell hung in the flues for over a week despite the high temperatures. Charlie used to tell us that in the old days other things got cremated in the flues as well, he reckoned he once found melted gold in the downtake of a boiler and said that more than one nagging wife had left the world that way!

Once the flues were dealt with, this took about four hours, Charlie and his men had a brew and then started on the scale. A boiler is like a kettle and if the water isn’t properly treated, scale builds up on the internal surfaces and interferes with heat transmission and inspection. Ideally, a sixteenth of an inch is just right, this actually protects the boiler plates. When I took over at Bancroft we had a bad scale build up and we had to spend a day and a half chipping inside the boiler to get it in good enough condition to inspect, I made a mental note to sort out the water treatment and get the scale down. It was over 120 degrees Fahrenheit in the boiler and scaling is hard work in a confined space. I could do about an hour but Jack could go on for ever it seemed. My earlier assessment of how hard he was is based on things like this, he just didn’t give up!

Stanley Challenger Graham

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

Stanley's View

scg1936 at talktalk.net

"Beware of certitude" (Jimmy Reid)

The floggings will continue until morale improves!

- Stanley

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 90301

- Joined: 23 Jan 2012, 12:01

- Location: Barnoldswick. Nearer to Heaven than Gloria.

Re: STEAM ENGINES AND WATERWHEELS

I soon sorted the water treatment out by sacking our supplier and getting a specialised firm in. This brought another good man into the engine house, Charlie Southwell who owned his own company in Manchester. He was a good man and showed me how to test the boiler water myself, something that had never been done before at Bancroft. By testing the water regularly and constantly adjusting the amount of water treatment I soon got on top of the scale problem and we never had to scale the boiler again.

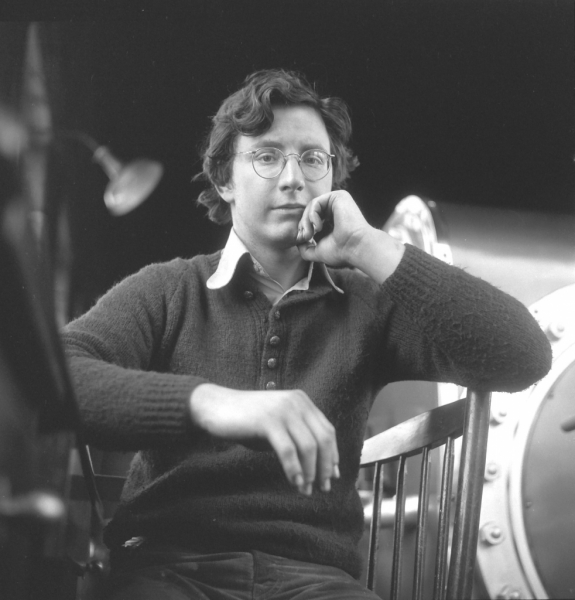

Charlie Southwell testing the boiler water quality.

Unless there was a repair to do to the brickwork in the flues, Charlie Sutton and the lads were finished by the end of the day and the flues were spotless, they did a wonderful job. All Ben and I had to do was clean up in the boiler house and then attack any jobs that needed doing to get us ready for the inspector. Most of the old inspectors were retired marine engineers, they were fully trained and certificated and were a good reservoir for the insurance companies to draw on. At that time we were insured with Commercial Union and, the inspector was Ron Ellerby from Dewsbury. He knew his job, knew the boiler and had evidently made up his mind to trust me. This meant that he didn’t want everything doing by the book every year, he used his head and just did a selection of jobs. This was the sensible way to go about looking after the boiler and I think he appreciated the fact that I was asking his advice instead of regarding him as an enemy which was the way George had treated him. All he asked for that first year was to have the feed valve stripped for inspection, this was only a small job. The main part of his inspection was the internal inspection and ‘hammer test’. This consisted of tapping the rivet heads with a small hand hammer. A ¾ lb. hammer was plenty big enough, all he was listening for was a difference in note which would alert him to a cracked or loose rivet. Exactly the same inspection used to be given to the tyres on the wheels of railway wagons, the ‘wheel tapper’ would go down the train tapping the wheels with a long handled hammer, any discrepancy in the note given off alerted him to a fault.

We got through the inspection with no faults and could then start to lace the boiler up again. We cleaned all the mating surfaces on the joints of the manholes and any fittings we had taken off, fitted new packings and re-made the joints. A bit of care here could save a lot of work later, the better a joint was prepared the less trouble to deal with it the next time it came off and you had no leaks in between. We would give the boiler a dose of water treatment through the lid before shutting it up by chucking a couple of buckets of compo in and then fill it with water to working level with the fire hose. In between these jobs, Ben and I had drawn all the fire bars out and cleaned them up and inspected them. You wouldn’t believe how much space two mouthfuls of fire bars took up when stacked in the bunker bottom! It usually took us the rest of the week to get the boiler ready for steaming.

One interesting side issue here was the fact that we used sheets of special jointing compound to pack flanged steam joints. Newton told me that on the railways no packing was allowed, the mating faces were perfectly prepared and simply painted with a mixture of red lead and a light oil derived from condensing the volatiles from hot wood. Funnily enough this oil was the same thing that we used to call Driffield Oil which was used as a disinfectant and lubricant when calving cows. The railway companies did this to avoid the danger of blown packings on the footplate which could be very dangerous as there was no escape for the crew if this happened in such a confined space as the cab of a loco at speed.

Once we had dealt with the boiler there might be odd jobs to do on the engine and repairs in the rest of the mill. We usually managed to get two or three days off but that was our holiday! On the Saturday before we were due to start I would come in and light a fire in the boiler. I wouldn’t use the stokers but just build a big slow fire by hand firing and leave it with the dampers just cracked open to smoulder for 24 hours to warm the boiler slowly. Steam built up slowly and warmed the main steam line to the engine. We had a bypass on this pipe which when open, allowed steam to travel from the steam main into the high pressure cylinder, from there it could wander through into the rest of the engine. Any condensation drained away through the cylinder drains which were left open. The result was that as the boiler warmed up, so did the engine.

On the Sunday we would steam the boiler to 150psi and roll the engine over once it was warm. A good practice to follow here was to roll the engine over with the barring engine for a couple of revolutions, this ensured that there were no surprises like a cylinder full of condensate because a drain was choked. Once we had done this the main valve was opened and the engine run for five minutes and all the oils checked. We then knew we were ready for the following morning when all the weavers were back from holiday. The boiler was left with a full head of water and steam and about 25 shovels of coal in each furnace smouldering away to make up for heat loss during the night. This was called ‘banking’ the boiler. Because the settings were cold we had to make sure we were at work in good time on the first day back at work and started with a full boiler, steam as high as we could get it and good fires in the furnaces. By the middle of the week when the settings had got hot things were a lot easier. The fires in the boiler wouldn’t be let out again until the next holiday which was September, this was when the firebeater and I tried to get a weeks holiday in because we didn’t flue then. George always used to have it done but I reckoned there wasn’t enough dust from three months summer firing to warrant it.